Today I share my deeply lovely conversation with the amazing Esther Derby, Author, Coach and author of, most recently, “7 Rules for Positive, Productive Change.”

Esther started her career as a programmer, and has worn many hats, including business owner, internal consultant and manager. From all these perspectives, one thing became clear: our level of individual, team and company success was deeply impacted by our work environment and organizational dynamics. As a result, she has spent the last twenty-five years helping companies design their environment, culture, and human dynamics for optimum success.

She's a founder of the AYE Conference, and is serving her second term as a member of the Board of Directors for the Agile Alliance. She also was one of the three original founders of the Scrum Alliance.

Esther has an MA in Organizational Leadership and a certificate in Human System Dynamics.

We discuss Systems thinking in problem solving, the cobra effect, Clock time vs Human time, the power of invitation, Ritual vs Ritualistic thinking and how forests are a better metaphor for change than installing a new OS.

Enjoy the conversation!

Show Links

Esther Derby on the web

7 Rules for Positive Productive Change: https://www.amazon.com/Rules-Positive-Productive-Change-Results/dp/1523085797

Back when it was 6 rules!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BDyoUdVHwbg

Kairos vs Chronos: Clock time vs living time: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kairos

Forest Succession as a metaphor for change: https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/ecology/community-structure-and-diversity/a/ecological-succession

“People are easy to see. People are easy to blame. Systems are hard to see and you can't blame systems.”

The Laws of Open Space:

https://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/Open_Space_Technology

Ritual vs Ritualized: The Power of Ritual to create a safe container

Esther on Retrospectives:

https://www.estherderby.com/seven-ways-to-revitalize-your-sprint-retrospectives/

https://www.amazon.com/Agile-Retrospectives-Making-Teams-Great/dp/0977616649

How to facilitate Safety:

“I have people fill-in-the-blank in two different index cards. And the first index card says, "When I don't feel safe, I fill-in-the-blank," and then I collect all those, and I have them do another index card that says, "When I feel safe, I..." They fill-in-the-blank and I collect those, and I shuffle them all up, and then I read all the ones about, "When I don't feel safe, I..." Sometimes I hand them out to people in the room, just at random and they read them.

Then I have people read the ones about, "When I feel safe..."

Then I say, "What do we need to do at this time, in this meeting, so we can live into this?"

The Use of Self in Change: “The success of an intervention depends on the interior condition of the intervenor” – Bill O’Brien, former CEO of Hanover Insurance

Radical Participatory Democracy: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radical_democracy

Virginia Satir: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virginia_Satir

Full Transcription

Daniel:

I will now officially welcome you to The Conversation Factory. Esther, I appreciate you making the time. I try to have a different opening question regularly, and I was thinking to myself, your book that's come out about rules for change, is there anything you're trying to change about yourself?

Esther Derby:

Yes. I have been trying, and actually been rather successful, in changing my weight over the last several weeks, months. I am changing how I schedule my time, so that I can have more time to put aside for art and work with fabric. I am making changes in my life to accommodate the fact that my husband is now retired, and he's just around in a different way, and showing up in a different way.

Daniel:

Those are all really good. Those are positive, productive changes.

Esther Derby:

Yeah, well, hope so.

Daniel:

That's really cool. So, it'd be nice to take a step back for those who have not met you and talk a little bit about what you see as your work, what you bring into the world.

Esther Derby:

Well, I would say at the very most fundamental level, what I care deeply about is making the workplace more humane. That is really what is fundamental for me.

Daniel:

Yeah, and it sounds like, from what I followed of your work, is that that comes from your own experiences in the underbelly of organizations? I'm guessing, not experiencing that all the time?

Esther Derby:

Well, I have had the experience of being treated in inhumane ways, but I have also done a lot of reading and research about the origins of management, which many people peg to the railroads, but management as a profession with multiple levels of hierarchy, and productivity counting, and so forth, and so on, specialization of labor. Assignment of labor based on specialized tasks actually dates back to plantations working with enslaved people.

Daniel:

And this is the system under which, not just programmers, which is your heritage, but most people are working under.

Esther Derby:

Sure, and I don't think managers consciously hold that in their minds. I don't think that they are consciously thinking about extracting maximum labor, but it is in our heritage. It's in our family tree of management practices and management thinking.

Daniel:

Yeah. Well, you used that term in one of your talks, this idea of the hangover of mechanistic thinking that we're suffering under. Can you talk a little bit about this legacy change versus this different approach to change that you're advocating now?

Esther Derby:

Well, I do think we have a hangover of mechanistic thinking, and we have this hangover of the origin of management practices, neither of which are particularly attuned to humans. In the earliest factories people came in from either rural situations, or craft situations, or small shop situations, where they had a lot of autonomy in many cases, not all but many, and they went into work situations that were far more regimented. Where they were expected to work by clock time, not necessarily by the time of the cycle of the day, and the cycle of the seasons, and they were in service to the machines.

Daniel:

Yes. Well, because the machines are cost they've paid for and they need to be paid for. They should be operating all the time to be maximally utilized.

Esther Derby:

And they need to be tended, right?

Daniel:

Yes.

Esther Derby:

They need to be tended, and taken care of, and watched, and so that legacy... Which I'm not against industrialization, but huge benefits, in terms of the material wellbeing in the world, and I'm not advocating we go back, I'm just saying we need to be aware of the family tree. So, that sort of factory thinking was then applied to many other sorts of labor. I mean, if you looked at insurance companies in the 60s when people were essentially... Their jobs were reduced to very fine level, "You do this task. You stamp this and then you hand it to the next person," so I mean, they were in some ways, very mechanized humans, and we still have the obsession with specialization, and breaking things down into discrete tasks at the atomic level, and very prescriptive job descriptions, and so forth and so on, all come from that legacy.

Daniel:

Yeah. Well, so then what's the new metaphor that we need? Because we talk about driving change, and installing, or implementing, right? I know it's triggering. I'll make sure there's an appropriate trigger warning at the beginning of the podcast, but this is something that we've all had, and then there's resistance to change and coercion.

Daniel:

So, what is the metaphor then? What's the new metaphor that we need?

Esther Derby:

I didn't put this in the book, because it didn't occur to me until after I had turned in the manuscript, but I've been talking about forest succession as a metaphor for changing organizations. So, not gardening because gardening you till the soil, and you plant particular things, and as long as you water them and weed them, everything will be fine. So, I think that is too simplistic, but a forest is something that does not just spring into being.

Daniel:

No.

Esther Derby:

It takes a process of... Well, if you start with rocky ground, let's just start with rocky ground. If one plant can take hold, that might hold a tiny bit of moisture in the soil that will allow another plant to take hold, and that plant might grow a little taller and put off some shade, which will let more moisture be held in the soil, which will make it possible for another plant to take root. And with all the roots, it'll start changing the soil and then different animals will come in, different insects, different animals, and then another plant community will be able to emerge. And so, it's not so much that we plant things and water them, it's that we create the conditions for something different to emerge.

Daniel:

Yes. So, what's coming up for me is, I mean, people want results. There's a hot problem, and we've got to do it in the next two quarters, and this approach sounds slow.

Esther Derby:

Well, I sometimes tell a story about a company where I once worked, where they were concerned about the projects coming in late and over budget. So, in the first year they said it's because people have never been held accountable. We will have consequences.

Daniel:

There will be consequences.

Esther Derby:

There will be consequences, and it had to do with people's bonuses. So, unless your project, and we're talking about year, or year and a half, two year long projects, unless it's within 5% of original schedule and budget, no bonus for you. Well, that didn't really make a difference, because large software projects were still large software projects, and they were dealing with tons of unknowns, and things turned out about the same way.

Esther Derby:

So, the next year they said, "Well, it's because we don't have professional project managers," and they brought in professional project managers, and things looked better for a while until the end of the year when, once again, things were late and over budget. So, they decided they needed a methodology and another year went by.

Daniel:

Oh, a methodology.

Esther Derby:

[crosstalk 00:09:16].

Daniel:

What methodology did they install in the...

Esther Derby:

Yeah, it shall remain nameless.

Daniel:

Right. Fair enough. I'm sure they didn't install Waterfall. Nobody has said like, "Let's install waterfall in our..."

Esther Derby:

Well, actually they did, because Waterfall was not the way we did projects when I started.

Daniel:

Yeah. Oh, wow.

Esther Derby:

Yeah, but anyways, so this went on for three years and at the end of the fourth year they declared victory. Various things had new names, so we no longer had documents, we had work products, we had job aides, we had compliance checklists, and so forth, and so on, but the results for the project were still the same. So, they took decisive action but it was a slow rolling non change. It went on for four years and essentially the same results, because they did not address the underlying influences and factors that held the pattern in place.

Daniel:

Yes.

Esther Derby:

Right, so I get that people want fast action and fast results, and sometimes you actually need them, right? If your company is about to go out of business, you take fast decisive action. You close it down, or find a way to infuse new cash and keep it running. So, sometimes you absolutely have to do that, but when you're looking for a long lasting change that is actually going to change what the system is capable of doing, I find that you have to really address these underlying factors. If you just slap something on top of it, the old pattern is going to reassert itself, so we have to really understand what holds this pattern in place. What are the things that we need to loosen up to create conditions for something else to emerge.

Daniel:

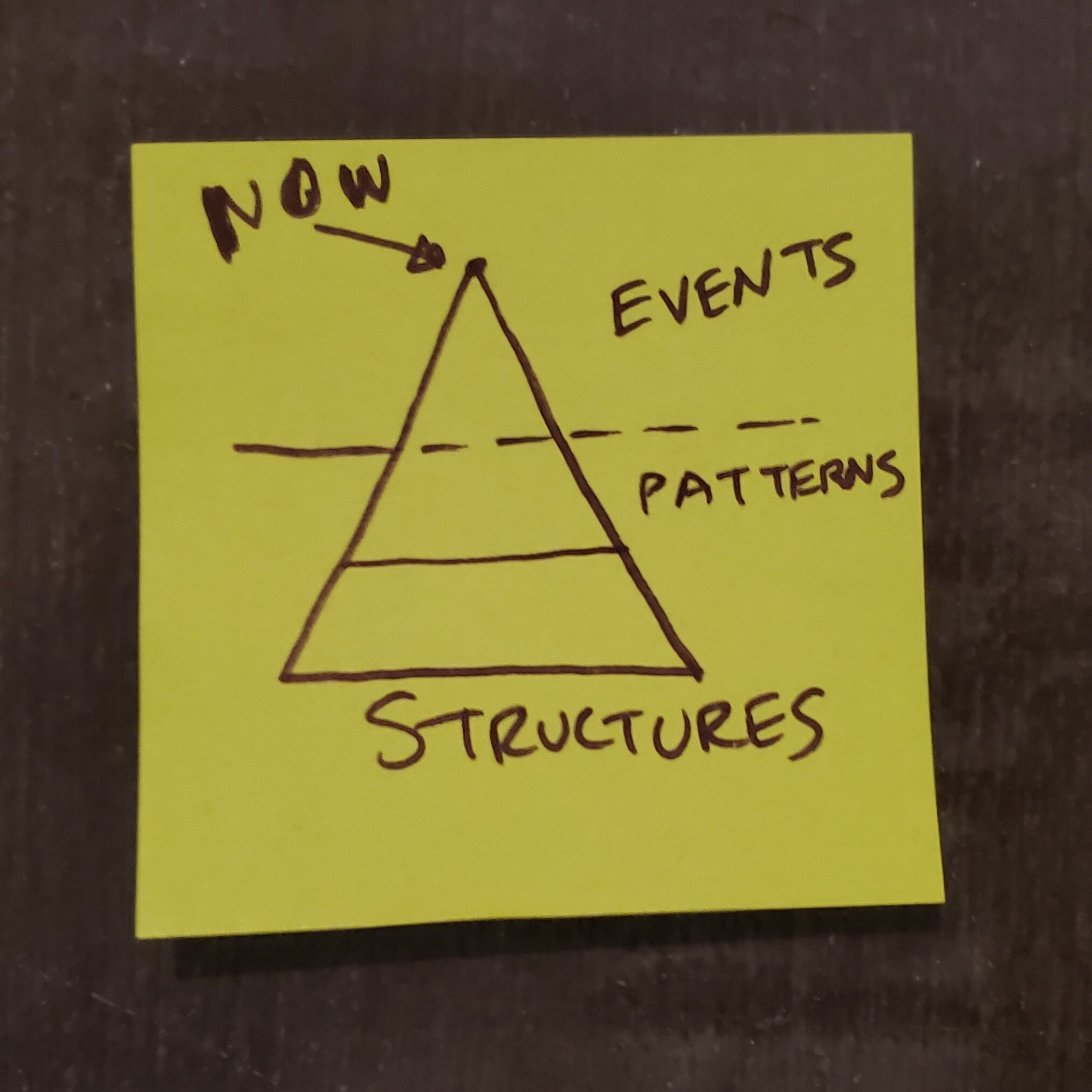

So, I'm looking at a diagram from a talk you gave, actually a couple of years ago, about people in patterns, where that the top of the pyramid is the event that you see now, and then there beneath the line is the pattern, and then beneath that are the structures. And if we react and respond to events, we have what you are talking about which is, it might work, or we might actually be not observing and depicting the true challenge, and therefore we can't create real change.

Esther Derby:

Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yep, we have to look at those, I call them structures, often, or influencing factors, that are driving that pattern, that are creating that pattern.

Daniel:

So, you use the word container, right?

Esther Derby:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Daniel:

Containers are what hold people's attention, and then patterns form around it.

Esther Derby:

Yep, they hold focus.

Daniel:

They hold focus and you talked really beautifully about how we're very bad at temporal awareness and good at spatial awareness, and I'd never really heard somebody talk about this idea that we are humans. In order to stay alive we need to have good spatial reasoning. And so, we...

Esther Derby:

It also staves off Alzheimer's.

Daniel:

Does it?

Esther Derby:

There's recent studies.

Daniel:

Which does? Developing more spatial...

Esther Derby:

Use of the parts of your brain that had to do with spatial reasoning and abstract reasoning. It's protective against Alzheimer's.

Daniel:

Yes. Wow. I'll have to do more design thinking workshops with my parents now.

Esther Derby:

There you go. Good son.

Daniel:

This is an amazing...

Esther Derby:

Okay, so I went on a little loop-de-loop there, so...

Daniel:

No, this is a long question. I think what I'm trying to get at is you've written about retrospectives, and I'm wondering how you create the time and space for people to really see the patterns and the structures that are... Because it seems like safety and reflectiveness you can't just react to the, "Oh, projects are late, let's get people's bonuses." That seems like low hanging fruit [inaudible 00:13:33] it's great. There's time.

Esther Derby:

Well, it comes from a particular way of viewing people, and performance, and organizations that says that if things aren't working it's because of skill and will. People are easy to see. People are easy to blame. Systems are hard to see and you can't blame systems.

Daniel:

I mean, I feel like people sometimes do blame the system, but...

Esther Derby:

Well, yeah, sometimes they do, but...

Daniel:

When the system has been co-created, it's been there for... No one person made the system, usually, we all make the system together.

Esther Derby:

Right, so I think that there is less learning with less reflection. It's possible to learn, and maybe not consciously and maybe not with a great deal of awareness, but reflection I think is a necessary component to learning. It goes against our bias towards action.

Daniel:

Yes.

Esther Derby:

So, in Western business culture, and particularly in the US, there's a huge bias towards action.

Daniel:

So, how do you invite people into a reflective space, so that they may go deeper into the challenge space?

Esther Derby:

Yeah. Well, I create invitation. I create spaces for it. Not everyone chooses to come.

Daniel:

Yes, but whoever comes are the right people.

Esther Derby:

Well, I think there's a law about that.

Daniel:

Yes. Well, yeah, and this is for listeners who are new to this, I was sharing the laws of Open Space with someone and I describe it as Buddhism for facilitators, it's sort of like...

Esther Derby:

That's a nice way to say it.

Daniel:

Whoever comes are the right people, whenever it starts is the right time.

Esther Derby:

Whatever happens is the only thing that could happen.

Daniel:

Yeah, so prepare to be surprised.

Esther Derby:

Yeah.

Daniel:

Can you help us? Can you help me structure invitation for that space better? What are the components of that good invitation to reflection?

Esther Derby:

Well, you already know one of them, Open Space, which always starts with an invitation, right?

Daniel:

Yeah.

Esther Derby:

It always starts, "Come help work on this problem if you have something to contribute to it." I sometimes find it helps to make things a bit of a ritual and that's what retrospectives are. They're a ritual, right? So, they're just carving out time and providing a structure, a format, that is likely to be conducive to a flow of conversation and full participation.

Daniel:

Yes.

Esther Derby:

The trick is not to let it become ritualized, so that it's the same every single time, because then you get habitual thinking.

Daniel:

Okay, now I'm going to take a very fine razor to the difference in ritual and ritualized.

Esther Derby:

Okay. It's possible I'm using the terms incorrectly.

Daniel:

I don't know if there... No, no, it seems like what I'm hearing you say is that, and this is maybe my own projecting, but a ritual creates a safe space...

Esther Derby:

It can.

Daniel:

And a pattern where we can sort of expect to know what is happening, but when something becomes ritualized, maybe that's when we fall asleep to it?

Esther Derby:

Yeah. Yeah. It just becomes rote behavior at that point, and when retrospectives become rote behavior, then the reflection is lost, right? So, people who are doing the same three questions for two years it's like, "Oh, our retrospectives are boring." Well, this is not a surprise if you've been asking the same three questions, or two questions, or doing the same meeting in the same way. It's not a wonder to me that things have gotten stale, and flat, and boring, and uncreative.

Daniel:

Yes. "Weary, stale, flat and unprofitable," that was how Hamlet described all the uses of the world, so how ought people to keep those... I mean, I'd never thought about how core retrospective is, because it seems like if it is regular, it's not about blame, it's just about looking back and noticing and seeing what is.

Esther Derby:

Yeah, I am fond of Shakespeare's, it's Hamlet quoted in Shakespeare, "Nothing is either good nor bad, but thinking makes it so."

Daniel:

Yes.

Esther Derby:

Right? It just is, and then you can respond to it.

Daniel:

Yes. How do we create that space for blameless retrospective though? It seems so challenging, potentially.

Esther Derby:

Well, it depends a lot on the culture of the organization and how people have been treated, right? So, if blame is pervasive in an organization, then I might not recommend that they do retrospectives, right? They may need to deal with that blame issue before they can hope to have an effective retrospective.

Esther Derby:

So, some of the things I do are I work with working agreements, for the particular retrospective if I think blame is going to be an issue. So, I have a number of working agreements I may work through with people, or I may let them bubble up themselves. I may talk about safety, psychological safety, and what that means. I have exercises that help people think about that. So, there's a lot of things you can do that can create at least a momentary place where people can bring things up. And in a culture that has been subject to blame, where people are blamed for things beyond their control, people are blamed for being coerced into commitments and then not making them, I don't expect deep learning at the outset. I expect people to just dip a toe in, right? Try something small, gain some belief that you won't be punished for bringing something up or suggesting an idea, but in organizations where there's a pervasive blame, it takes awhile for people to believe that something else is possible.

Daniel:

Yeah, they're waiting for evidence.

Esther Derby:

Yeah. Well, and who can blame them? It's reasonable.

Daniel:

Yes. What is an activity you use? Not to get you to reveal all your tricks live on the internet, but psychological safety seems to be a very ephemeral quality that people talk about. I've never heard somebody say, "I have activities that help people gain a sense of safety." How do we do that as facilitators?

Esther Derby:

I think the situation that felt most dramatic to me, or feels most dramatic to me, is when I have people fill-in-the-blank in two different index cards. And the first index card says, "When I don't feel safe, I fill-in-the-blank," and then I collect all those, and I have them do another index card that says, "When I feel safe, I..." They fill-in-the-blank and I collect those, and I shuffle them all up, and then I read all the ones that, "When I don't feel safe, I..." Sometimes I hand them out to people in the room, just at random, so I'm just distributing them at random and they read them. So, you just have this kind of pouring over you, and it's like ugh.

Daniel:

So, you read the first ones, the, "When I don't feel safe I," blank.

Esther Derby:

Right, and then you have people read the ones about, "When I feel safe..."

Daniel:

But not their own, right?

Esther Derby:

Not their own.

Daniel:

You anonymize it.

Esther Derby:

No, I've shuffled them. I anonymize them if I'm really... Sometimes I read them myself and it is astonishing. You can see a physical shift in people. You can hear it in their voices, right, and then I say, "What do we need to do at this time, in this meeting, so we can live into this?"

Daniel:

Yeah, because you've drawn the gap for people very clearly, yes?

Esther Derby:

Yeah.

Daniel:

I can't imagine anybody would hear all of that and say, "Well, who cares," right? It's up to everybody. I could see you create that tension and people want to resolve it in the positive direction.

Esther Derby:

Yeah. I wouldn't do that with every group I go into, but it is just palpable the difference. And people really, really yearn, and long, to act out of a sense of safety because that's when they can be creative, that's when they can take risks, that's when they can talk about the tough stuff, that's when they can be at their best, that's when they can take a chance on somebody, that's when they can take a chance on themselves, that's when they can connect and people yearn for that.

Daniel:

Because I'm just imagining when people say, "When I feel safe I contribute."

Esther Derby:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Daniel:

And this is what we really want.

Esther Derby:

It's what most people want to give, not everybody, but I mean, some people are just at a job to support their family and their life, and I think that's admirable, but many, many people want to contribute in a significant way. They want to have a purpose. They don't want to just be clocking the time, they want to be contributing in a meaningful way, and that sense of safety is connected to that.

Daniel:

I think that's a really beautiful exercise.

Esther Derby:

Yeah, feel free to use it.

Daniel:

I mean, so that's a safe container, right?

Esther Derby:

Yep.

Daniel:

Because of the anonymization... For sure.

Esther Derby:

And like I said, I wouldn't do it with every group, but I've done it with a number of groups and it's been very, very powerful. Sometimes I do a survey about how safe people say, and I give them a little scale, and say "I'll talk about anything without fear of retribution," and that's five and zero is, "I'm not bringing up anything. I'm not taking any risks." Again, I collect the responses, and I create a histogram, and people say, "What does this say about our ability to deal with the problems that are facing us?" And then they get to make choices about what they're going to do.

Daniel:

How many people would you survey to produce that data?

Esther Derby:

However many people are in the room.

Daniel:

Yeah. Oh, gotcha, like a survey in the room. Yeah.

Esther Derby:

And usually, I collect the little index cards, or slips of paper, or whatever and assuming I'm in person in a case like this, and then I put them in my back pocket, so everybody knows that they're not just laying around.

Daniel:

Yes, that's showing respect. What's interesting is that there's a very strong arc and there's a very strong close to that, that you're respecting the pieces of paper that they've created and spoken up. And what's interesting, it's funny, this definitely speaks to your OG programmer cred, but you're using index cards for this activity, right?

Esther Derby:

Index cards.

Daniel:

Index cards. Us new kids on the block, where it's all about the stickies, but I can see how putting those on the wall might actually be a little confronting.

Esther Derby:

Yeah, well I like stickies, too.

Daniel:

So, I can see how your ethos of respect for other people go into your rules for change, honoring what's currently existing, observing the system and respecting what's currently alive in the system, caring about the networks that are inside of the system. I'm curious how you sort of iterated into the seven rules in the book, because I know you were giving a talk just a year ago were there was six.

Esther Derby:

I know, but I wouldn't be a very good role model for change if I couldn't add a new rule. So, there was a time in my life when entering a new system, I did not stand in non-judgment. There was a time in my life where I...

Daniel:

I'm not going to stand in judgment of you of that. I understand that.

Esther Derby:

Thank you. I appreciate that. I appreciate it. I mean, it's like, "What the hell are people doing?" It's hard to influence people once you've flipped the bozo bit, right? It's very hard to influence people.

Daniel:

Wait, I'm sorry, for you it's hard to influence people when you've...

Esther Derby:

Once you flip the bozo bit on them. Do you know that expression?

Daniel:

I don't.

Esther Derby:

Oh, well in old programming, when you were actually dealing with bits, you could actually change a bit from a zero to a one. It was called flipping a bit, turning something on or off. And the bozo bit is saying, "I view this person as a bozo."

Daniel:

Gotcha. It's hard to un-say that.

Esther Derby:

Yeah. Yeah. It's hard to get your mind out of that and it's hard to influence someone once you put them in that category. So, I had to learn how to approach things differently, right? And in some ways, I was coming from that mechanistic legacy of standing in judgment, and things should be working fine, so I try not to be too hard on myself, but I had to find different ways if I actually wanted things to change and so, that's in some ways, the origin of when I started approaching these things differently. But I also I had the experience early in my career of seeing how one of my programs was a negative change for somebody, and I had the experience early in my career of making small changes, so that people could work more effectively.

Esther Derby:

So, the six rules was in some ways a little contest with myself to see if I could encapsulate my beliefs, and my experience, and my research about change in a very succinct way.

Daniel:

Yeah, to know what you're about?

Esther Derby:

Yeah.

Daniel:

I think this comes...

Esther Derby:

So, when...

Daniel:

Oh, sorry, go ahead.

Esther Derby:

Well, the first time I gave this talk, the talk Six Roles for Change, was in 2015 and I didn't really know at the time it would turn out to be a book.

Daniel:

What made you decide to make it a book? What was the pull towards that, because you've written other books, not every idea you have becomes a book?

Esther Derby:

No, I went for about 10 years without writing a book. I see so many instances of companies, and people in companies, who really want something to be different and the methods that they have inherited are insufficient to actually bring about the sorts of change they want, sometimes they long for, they yearn for, because they don't address the underlying pattern.

Esther Derby:

And many of the traditional change methods are premised on top down control, pushing change onto people and incorporating plans to overcome resistance, not recognizing that the way they're going about it has actually engendered this thing they call resistance, right?

Daniel:

Literally, creates the thing that they are planning for.

Esther Derby:

Yeah, yeah. Exactly. So, I was tweeting with a friend of mine, who was in a change management class recently, and they were being told that they had to have a plan to overcome resistance in their change plan. So, it's still out there, right? So, it just seemed to me that people needed a different way to approach change that was more humane, more humanistic and more informed by complexity science and working with complex adaptive systems.

Daniel:

Yeah. Well, and it seems like observing the system means, in some sense, respecting what is working in it?

Esther Derby:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Daniel:

Having some like, "Whoa. Wow. Somehow it works." So, you don't go in and say like... You respect the fact that somehow there is something alive in the system before you start messing with it.

Esther Derby:

I like the fact that you're saying there's something alive in the system. I like that a lot.

Daniel:

Yeah, that comes from appreciative inquiry for me.

Esther Derby:

I like that languaging.

Daniel:

There's something. It's living something, in some way.

Esther Derby:

Yeah. There's always something worth saving, right. And there's always stuff that's working, otherwise the company would be out of business, or the organization would have folded, so it's worth looking for that and building on it, which again, is sort of the genius behind appreciative inquiry.

Daniel:

So, I want to go back to the sticky note I wrote before we started talking about the use of self, because I feel like the ultimate container for this is the change agent. There's a person who wants change, and who is absorbing the challenges, and who says to themselves, "I want to do something," and then there's this feeling of having to absorb the other person's perspective and having to think about, an empathize. There's a lot of work, internal work, that has to be done in the person who wants to do the change. I don't know if that's what you meant by use of self, but that's what it sparked off on me.

Esther Derby:

Well, I think all of those statements are true. I come at that statement from conversations I've had with friends of mine who are licensed clinical social workers, and in study after study, it has been shown that if you have two people with roughly equal professional skills, they went to the same school, they learn the same skills for dealing with their clients, which may be individuals or it may be organizations, what makes the difference is the ability to show up, be present, connect, and be empathetic. That's what makes the difference, and that has to do with who you are as a person, and how you bring yourself, and your experiences, and your personality to your work.

Esther Derby:

So, for people hoping to bring change, yeah, they are absorbing a lot, which means they have to call on their inner resources, and they need to be empathetic to others. So, they need to call on their empathy. They need to call on their patience. They need to call on their ability to observe and to withhold judgment, because that's not a natural tendency for most of us who are brought up in the West. So, we have to work at it, and you're right, it is hard work and I think it's super, super helpful for people to have a support network.

Daniel:

Yeah. I'm looking at pay attention to networks is something we're supposed to do to change a system, but obviously all of these rules ought to apply to change on oneself or change with oneself.

Esther Derby:

Yeah. It's fractal. I suppose [inaudible 00:35:25]. One human, or 10 humans, or 10,000 humans.

Daniel:

I would hope so. How do you take care of yourself as a change agent, because I mean, that is what you do.

Esther Derby:

Yeah, it is what I do.

Daniel:

You come in and you help organizations, architect, and facilitate change.

Esther Derby:

Yeah. I help individuals do that and I help companies do that. Well, I try to get enough sleep. I try to eat well. I have a support network. I have a number of dear friends who act as sounding boards, or sometimes they let me sing my complaints choir to them, so I have that. I have the support network. I walk in the woods. I walk in the city. I ski. I do stuff that takes me out of this. I quilt. So, I have other things that bring me a bit of sanctuary and a place to refresh and look at things from a different perspective, so I'm not always immersed in it.

Daniel:

Taking time.

Esther Derby:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Daniel:

I find it very challenging to do that. There's a lot of demands that I put on myself, so it's encouraging to hear you talk about those pieces.

Daniel:

I feel like we're really getting close to the end of our time together. I want to respect your time. What haven't we talked about that we should talk about? What have we missed off?

Esther Derby:

Well, we've covered a lot of really, really deep and interesting topics, so I'm not sure I'm feeling that anything has been neglected.

Daniel:

Oh, that's wonderful.

Esther Derby:

I'm sure there are other things we could talk about, but I think we talked about some really significant things.

Daniel:

So, I guess one question I have is, aside from your book, which people should read, what have you fed yourself with? What are some of the most significant places you've gone to feed your head around these things, these issues we've talked about?

Esther Derby:

So, in terms of studying, or reading, or absorbing?

Daniel:

When it comes to your philosophy of lack of coercion and change, that's something that's really deep in you and I'm wondering where you've fed your professional mindset from? What wells you're drinking from?

Esther Derby:

Well, in some ways, it goes back to early in my life. In some ways, it goes back to when I was doing my master's program and was exposed to radical participatory democracy and the power dynamics that exist in many corporations. So, I think that helped me articulate a lot of those things. I'm also been studying Satir work for, I don't know, almost 30 years.

Daniel:

I'm not familiar with Satir work, and I know you mentioned it in some of your talks.

Esther Derby:

Yeah, Virginia Satir. She was a social worker and she really pioneered the idea of a family as a system. So, you can't just say, "Well, Suzie's the problem," you have to look at the whole family and how Susie is responding and what the dynamics and the relationships are there. So, while I'm not a therapist and I'm not a social worker, I have studied this model, because I find there are many parts of it that can be used in a business context, in organizational context, that help people be more fully human, be more fully themselves, be more congruent, be more aware of their own resources, and to step into the world in a way that is more healthy for them. So, I think that's a really deep well for me.

Daniel:

That's cool. I'll check that. It's funny, I look at some of the stuff that we do like drawing stakeholder maps and drawing problems as art therapy. When I ask people to draw their jobs, and I see where all the people in their jobs, and where aren't the people. Systems are complex and people are complex. I think there's a lot to unpack in that. I really appreciate it. I'll look her workup.

Daniel:

Well, all right then. I think we're going to close it out there and I'll ask you to stay on for one more moment.

Esther Derby:

Sure. I really appreciated this conversation. It was really lovely having this time to talk with you.

Daniel:

Thank you. Me too. It's nourishing. I'll call scene.

Daniel:

Just wanted to make sure everything felt includable, I don't think we got into any rough territory?

Esther Derby:

Uh-uh (negative), and my dog was quiet the whole time. This is a miracle.

Daniel:

I'm glad.

Esther Derby:

I can hear her snoring in the other room, but snoring is not that bad.

Daniel:

I actually did a podcast episode where the guy had to hold his dog and then the dog finally fell... That was the only way to have a silent workshop podcast call.

Esther Derby:

I get that. Yeah, I'm going to have another cough drop, excuse me.

Daniel:

Thank you really for doing this. It's really interesting. It's like we all come from our own heritage, and our own perspectives, and it's just I really love the way the things that you present, and that you share, because I think it's important stuff.

Esther Derby:

Thank you. I've really appreciated this conversation. I didn't just say that to say it. You are good at conversation.

Daniel:

It's funny, the idea of coercion at the base of it is respect for others, and just understanding that conversations, I've come to respect them more and they make me a little bit more careful with them.

Esther Derby:

Well, you use them to connect and to understand.

Daniel:

I do.

Esther Derby:

So, that's lovely.

Daniel:

Well, I hope this isn't our last conversation.

Esther Derby:

I hope not. I hope that this is the start of many conversations.

Daniel:

Thank you!