My guest today, Emily Levada, is a seasoned Chief Product & Technology Officer. Currently, she is the Chief Product Officer and Interim co-CEO at Embark Veterinary, a company dedicated to leveraging genetics to enhance the health and longevity of dogs. During her tenure, the company has achieved notable recognition, ranking as the #3 fastest-growing private company in Massachusetts and earning a spot on Forbes' list of promising venture-backed startups.

She also serves as a Board Member at JCC Greater Boston, bringing her expertise to contribute to the organization's growth and development and holds a significant role as a Member of the Customer Advisory Board at UserTesting, where she actively engages in guiding and advising the company.

Emily is also a two-time podcast guest, my first ever! We did an episode a few years back where she shared some wonderful insights and frameworks about Trust, Communication and Psychological Safety in teams.

Emily was also gracious enough to be a guest mentor for the Innovation Leadership Accelerator cohort I co-ran with my friend Jay Melone from the product innovation consultancy New Haircut some years back.

In this conversation, we sat down to talk about managing organizational emotions, especially negative emotions, and especially during critical junctures, like layoffs - something that many folks have been through, and many folks in the past year. I knew that Emily had some experience with this in the past and had some great thinking to share around this crucial leadership topic.

There’s no *good* side to be on in a downsizing event - the people who are losing their jobs and income are also losing a sense of identity and need to navigate an uncertain future. But the loss of identity and the need to face an uncertain future is also true for the folks who are still with the company - both the “rank and file” and the leadership.

Layoffs done poorly can dent a company culture.

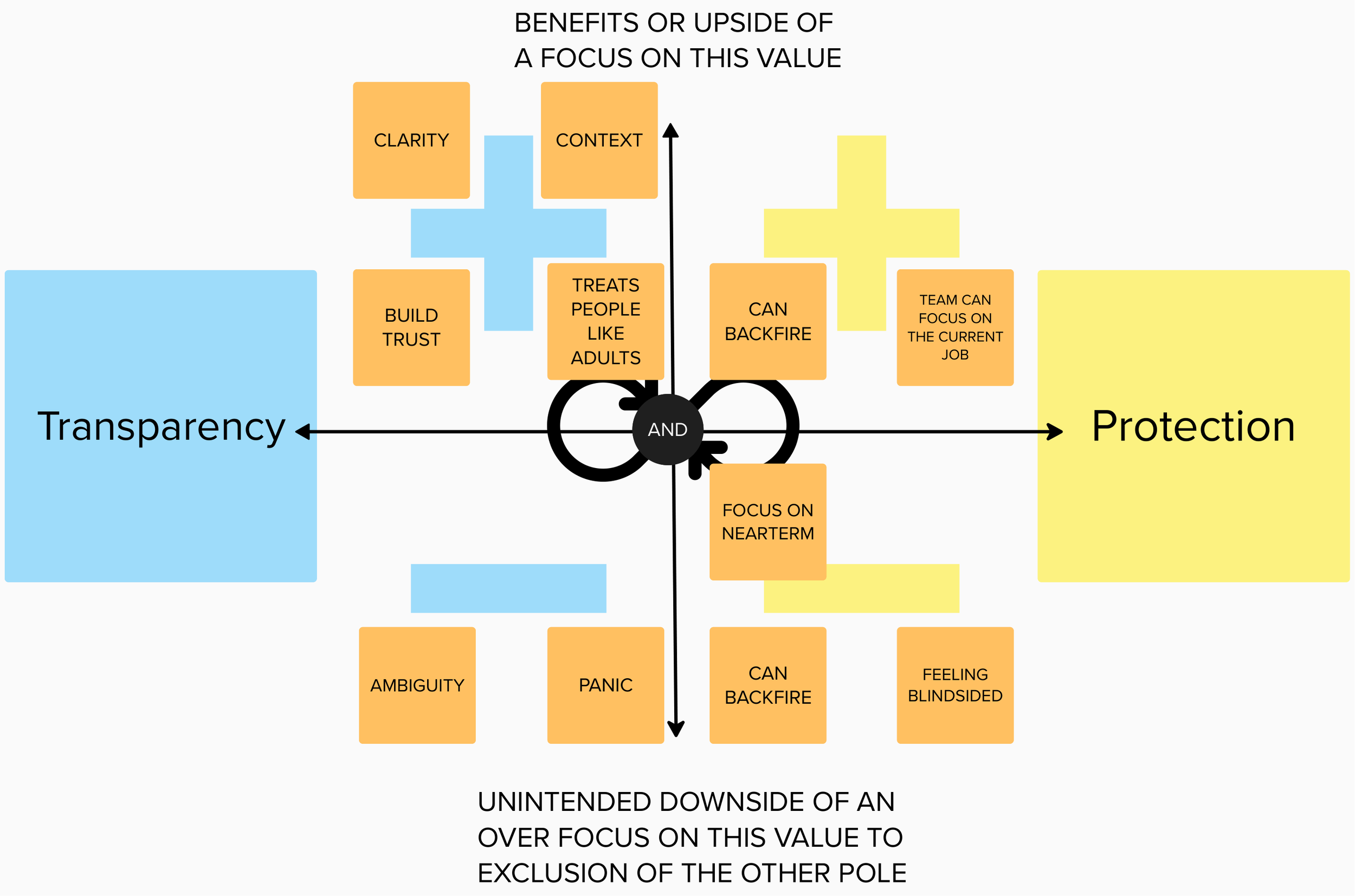

Emily emphasized the importance of transparency in the period leading up to a layoff, as it builds trust and can mitigate negative emotions.

On the other hand, leaders often have a desire to protect people from such difficult conversations until the last possible moment, so the whole team can focus on their day-to-day jobs.

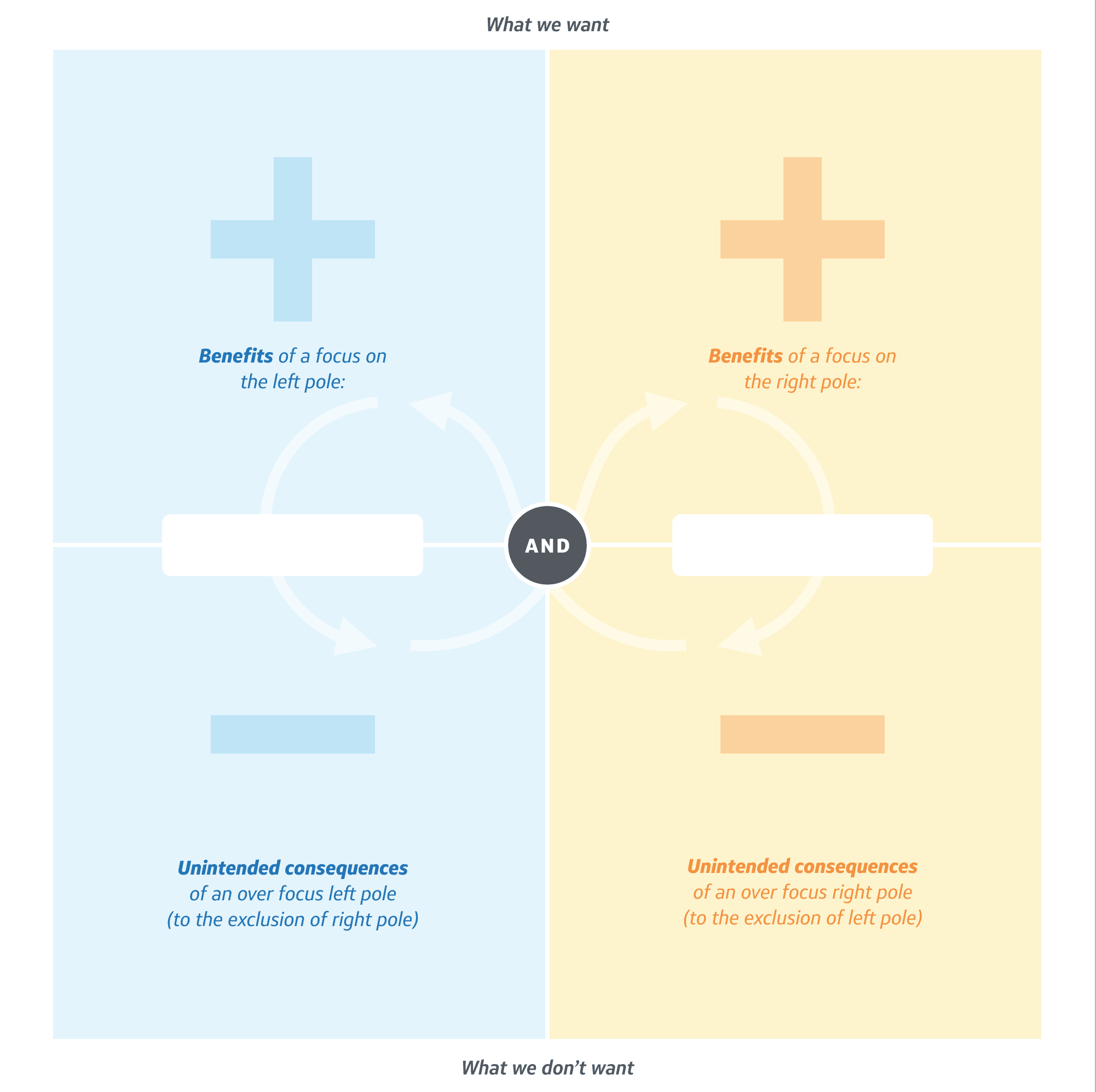

I explored this polar tension between these two fundamental values, transparency and protection, with Emily using a tool called Polarity Mapping, developed by Barry Johnson Ph.D., the creator (and registered trademark holder!) of The Polarity Map®! You can read more about polarity mapping in my friend Stephen Andserson’s short blog post here and check out Dr. Johnson’s company, Polarity Partnerships here. IMHO, Stephen’s version of Barry’s diagram (below) is a bit clearer!

The basic idea of Polarity mapping is that often we feel pulled by two values, like:

Should we focus on Innovation or Efficiency?

Should we prioritize Deadlines or Quality?

Growth vs. Consolidation?

Short-term Gains vs. Long-term Organic Growth?

Centralization vs. Decentralization?

(thanks for these examples, Stephen!)

In my own coaching work, I’ve found leaders can struggle to navigate conflicting parts of themselves, forming inner polar tensions that leave them feeling stuck, like:

“I need to be flexible vs I need to be firm”

“I need to lead the conversation vs I need to let the conversation flow”

“I need to be aggressive or I have to be more passive”

“I need to listen more vs I feel the need to fix challenges”

“I want to be authentically myself vs I need to be a chameleon to get by”

And because we get pulled between them, and feel the polarity to be an unwinnable double bind of “damned if I do,” we kind of flub the balancing act. Polarity mapping asks us to be ultra-specific about the positives of both values AND to be very clear on the downsides of over-indexing on one value to the detriment of the other.

Doing a mapping like this can help us thread the needle of polarity, and look out for the early warning signs of over-indexing in one direction or another.

Below is a version of a polarity map for the tension Emily describes in our conversation, between Transparency and Protection.

Emily points out that these polarities pop up, not just at crucial moments in a business like layoffs, but in day-to-day operations, too.

Leaders can feel that Emotions are Inconvenient, but Team Emotions have real impact

Emily shares the top three negative organizational emotions she finds can deeply impact a team’s ability to learn (i.e., be willing to experiment), be creative (i.e., being able to innovate) and be fundamentally effective:

Anxiety (Fear)

Boredom

Apathy

Fear, anxiety, and boredom are detrimental to creativity and productivity in knowledge work. Leaders need to address these emotions and create an environment that fosters engagement and challenge - and ultimately, create a learning organization.

“People cannot do creative knowledge work when they feel fear and anxiety and boredom. Those things are just incompatible.”

Emily suggests that well-run one-on-one meetings are crucial for understanding how team members are feeling and detecting signs of overwhelm, underwhelm, or “whelm” in their job. One-on-ones can help build a foundation of trust and safety, on which we can build honest and productive conversations.

Emily also shares some straightforward approaches for shifting these key negative emotions:

Anxiety: focus on building psychological safety for teams experiencing anxiety, and provide more transparency and context.

Boredom: create relevant challenges

Apathy: create accountability and challenge for teams experiencing apathy

AI Summary By Grain

Daniel and Emily discuss the importance of transparency and managing emotions during layoffs, emphasizing the need for psychological safety and building trust with team members. They suggest regular check-ins, icebreakers, and pulse surveys to gauge team emotions and prevent negative impacts on productivity. Emily explains that effective accountability requires understanding how a person's job connects to company goals, setting appropriate metrics, and articulating success with clarity.

Key Points

Emily discusses the importance of clarity and messaging in advance of a layoff, and how it can build trust with employees (11:06)

Emily shares an example of how to signal potential risks without creating panic, and they discuss the balance between protecting employees and providing transparency (16:08)

Daniel and Emily discuss the need to optimize for creativity and adaptability, especially after major changes like layoffs (32:41)

Emily suggests developing a measurement system to understand where the team is emotionally, including individual conversations, surveys, and observation. She also recommends doing a listening tour to hear from team members at all levels. (34:45)

Daniel and Emily discuss the belief that people want to do great work and the role of psychological safety in creating a context for great work (48:54)

Links, Quotes, Notes, and Resources

Trust, Communication, and Psychological Safety with Emily Levada

The Joys of Polarity Mapping, by Stephen Anderson

Minute 1

Daniel Stillman:

And this is something that comes up a lot, which is like, how do we do layoffs? How do we manage the process, but also the emotional space and damage, blow back that happens. And what do we do about the team that's left over? As a product leader, how do you think about this thing that is pretty much inevitable and currently very common?

Emily Levada:

Yeah. I mean, I wish it wasn't inevitable. I mean, I wish we all were able to manage our businesses effectively enough that we never over-hired, overstaffed, had imbalances in the skills and capabilities or anticipated changes in the market. All of those things. At some level, doing a layoff is a failure of leadership's ability to plan for the future effectively. And of course, leaders are humans and it's impossible to predict the future. And that's sort of what I think makes it feel inevitable at some level. I do think that there's a couple of things that are really important. And the first, which I think is the hardest, and the one that I find people push back against the most is actually transparency in the period leading up to a layoff. Because the reality is that... Well, I think people know this, and being a product manager is a lot about managing other people's expectations. And there's this notion that when reality is better than your expectations, you experience delight and when reality is worse than the expectations, you experience disappointment or other negative emotions.

And usually we're talking about customers here. And one way that you can solve for that or drive customer delight is by making the reality better. But another way you can do it is by mitigating people's expectations. And you don't want to sort of overpromise and under-deliver. And I think that the more I've done layoffs, the more I felt like, hey, look, there's something about clarity when a layoff happens about why that decision is being made, about either the business hasn't been in a good place, or the business has this problem and we need to solve this problem. A lot of layoffs come out of the blue and you have leaders who saying, everything's going great, everything's wonderful. Oh, by the way, we're laying off 15% of the company. And that all of a sudden breaks trust because those things are not compatible with one another.

Minute 15

Daniel Stillman:

So do you want to talk about why it's important to learn how to navigate negative emotions and what's important about being able to lean into those?

Emily Levada:

Yeah, sure. I think there are also these misconceptions. I think a lot of managers think emotions, well, a lot of managers think emotions are inconvenient.

Somehow a thing that they have to deal with, but not their responsibility, explicitly, not their responsibility. And also that emotions are only the realm of the individual and versus the realm of the team or the organization, which isn't to say that individuals don't have emotions, but I'm also interested in this sort of organizational emotion that the sort of team emotion and thinking about how you manage that. And I think the real reason why, I mean, what I'm interested in is, how do you create organizations that can move as quickly and effectively as possible towards the results they're trying to drive? And the framework that I use when thinking about this is basically focused around learning. The idea being that if you can learn effectively, you can do anything. You can sort of move into any new space. You can find value sort of anywhere, and you're sort of gated by your ability to learn what's going to be of value quickly.

But I find that that goes hand in hand with a bunch of other things that we care about, creativity and risk taking and resilience and a bunch of other things. And so how do we get our organizations and the individuals in our organizations into this headspace, into this mood, into this emotion where they can be focused, they can be in the zone, they can be resilient and optimistic. And my perspective is that there are sort of three major negative emotions that detract from our ability to do this effectively. Those are fear and anxiety, boredom and apathy.

And a lot of the reason that I have come to those three is they show up over and over again as you review organizational behavior work. And a lot of the frameworks that I've come to really love and to utilize in my day-today, you see these three emotions or versions of these three emotions show up over and over again. And at some point I've started to feel like, hey, look, a lot of what it takes to actually create the conditions for success in my team is about how do we manage anxiety, boredom, and apathy in the team. Because if you can manage those effectively, you can create a team context and a team environment where that learning and that creativity and that resilience is possible.

Minute 35

Daniel Stillman:

So the value of challenge can activate someone in a good way. It can give them a sense of, there's impact. We want to connect with what they're doing to not just output, but impact. And if we over-index on challenge, then people will just feel, we'll go back into that anxiety zone.

Emily Levada:

I think that's right. And I think also there's an underlying value here, which is maybe not in a polarity, but which is as a leader, in order to do this effectively, in order to create effective accountability for that team, you actually have to get your shit together.

Daniel Stillman:

You want to break that down for us a little bit?

Emily Levada:

You have to understand how that person's job connects to the company goals. You have to be aligned on what you're trying to accomplish. You have to set an appropriate metric or measurement for that person to hit. You have to be able to articulate to them with clarity what success looks like.

And a whole bunch of things that sometimes managers are not good at, but it's a good opportunity to say, oh, this is what my team needs from me, and therefore this is what I should focus on in creating this accountability and this productive pressure.

More About Emily Levada

Emily Levada (She/Her), is a seasoned Chief Product & Technology Officer. Currently, she is the Chief Product Officer and Interim co-CEO at Embark Veterinary, a company dedicated to leveraging genetics to enhance the health and longevity of dogs. During her tenure, the company achieved notable recognition, ranking as the #3 fastest-growing private company in Massachusetts and earning a spot on Forbes' list of promising venture-backed startups.

She also serves as a Board Member at JCC Greater Boston, bringing her expertise to contribute to the organization's growth and development and holds a significant role as a Member of the Customer Advisory Board at UserTesting, where she actively engages in guiding and advising the company.

Full Transcript

Daniel Stillman:

Okay. So Emily, I'm so grateful that you made the time for this conversation. You're actually the first, second time interviewee conversationalist.

Emily Levada:

Wow.

Daniel Stillman:

And I'm-

Emily Levada:

What an honor.

Daniel Stillman:

Well, yeah, it's very kind of you to say. Welcome back to the conversation factory. I get to say it for the first time.

Emily Levada:

Thank you. I'm glad to be back.

Daniel Stillman:

The association, when I think of layoffs, I think of... I saw you post recently on, well, I guess it's not that recently anymore now, on LinkedIn around, a leader's guide to managing organizational emotions and your desire, your interest in creating a learning organization. And I know that you've been involved in and have been responsible for layoffs in the past. And this is something that comes up a lot, which is like, how do we do layoffs? How do we manage the process, but also the emotional space and damage, blow back that happens. And what do we do about the team that's left over? I've watched you try to find jobs for people from your last company after layoffs, find jobs for people you've had to lay off. You do put a lot of love and care into it. As a product leader, how do you think about this thing that is pretty much inevitable and currently very common?

Emily Levada:

Yeah. I mean, I wish it wasn't inevitable. I mean, I wish we all were able to manage our businesses effectively enough that we never over-hired, overstaffed, had imbalances in the skills and capabilities or anticipated changes in the market. All of those things. At some level, doing a layoff is a failure of leadership's ability to plan for the future effectively. And of course, leaders are humans and it's impossible to predict the future. And that's sort of what I think makes it feel inevitable at some level. I do think that there's a couple of things that are really important. And the first, which I think is the hardest, and the one that I find people push back against the most is actually transparency in the period leading up to a layoff. Because the reality is that... Well, I think people know this, and being a product manager is a lot about managing other people's expectations. And there's this notion that when reality is better than your expectations, you experience delight and when reality is worse than the expectations, you experience disappointment or other negative emotions.

And usually we're talking about customers here. And one way that you can solve for that or drive customer delight is by making the reality better. But another way you can do it is by mitigating people's expectations. And you don't want to sort of overpromise and under-deliver. And I think that the more I've done layoffs, the more I felt like, hey, look, there's something about clarity when a layoff happens about why that decision is being made, about either the business hasn't been in a good place, or the business has this problem and we need to solve this problem. A lot of layoffs come out of the blue and you have leaders who saying, everything's going great, everything's wonderful. Oh, by the way, we're laying off 15% of the company. And that all of a sudden breaks trust because those things are not compatible with one another.

Daniel Stillman:

Right.

Emily Levada:

And so I think particularly with the last layoff that I did, it was very important to me that the leadership team was messaging in advance. And it was as simple as, hey, we're having trouble balancing the budget, which was the reality. We were having trouble squaring our revenue projections with our costs, and the largest part of our costs was headcount. And we were going through the process of trying to figure out what are all of the other ways that we can balance this budget that are not doing layoffs, but we try to be at least open about the fact that that process was happening and not that everything is wonderful and the plans are all coming together and it's all going to be great. And I think part of the reason that people are afraid of doing that is because they feel like it creates unnecessary anxiety in the organization in advance, and it creates sort of discontent or fear. And for me, I think there's some amount of trading off anxiety before a layoff for trust building in your willingness to be transparent with an organization after a layoff.

Daniel Stillman:

Wait, so let's underline that because you're saying that the blow-back for not being... Well, the downside of being transparent is you can create anxiety, but if you are as clear and transparent as you can be or as you feel you can be gain trust?

Emily Levada:

Right.

Daniel Stillman:

Both of the team before, but also really importantly of the team that's remaining.

Emily Levada:

That's remaining.

Daniel Stillman:

Afterwards.

Emily Levada:

Right. And that also the problem that I have seen where you don't give any indication the layoffs coming, you do a layoff. Now the people who are remaining are saying, well, how can I trust you that when you say things are going well, that they're actually going well. And you have to start earning back trust with the people who are there. But really, I mean, what I'm talking about now is basically all sort of emotional management.

Daniel Stillman:

Yes.

Emily Levada:

None of this is the actual ticking and tacking of how you do a layoff. It's all about how you think about what is fair and right and just and produces the overall fewest negative emotions, both before and after.

Daniel Stillman:

So what's the opposite value? So on one hand, transparency is valuable because if we index on it, we create trust. And if we under index on transparency, we can create anxiety because people don't have clarity, we create anxiety for them. On the other hand, I feel like people say, I want to play this close to the vest. And there's reasons for that. What's valuable and good about being thoughtful or cautious or intentional about what you share with your team?

Emily Levada:

Yeah. I mean, I don't want this to sound like there's not a lot of discretion that goes into what's shared or when it's shared. I think there's a difference between the sort of simmering of anxiety of, hey, there might be a correction that needs to happen in the business and it could impact me, and does that make me demotivated or even consider leaving this company? But I think, what I'm not suggesting is the kind of transparency that creates panic.

Daniel Stillman:

Right.

Emily Levada:

Which I have also seen. So I have seen some leader be like, "Oh yeah, the layoff's coming in two weeks." And then everybody's like, "Wait, give me all the rest of the information." And then they're like, "Yeah, nope. Can't share that information. Don't have more details." Then you just have panic for two weeks. But I think it's the signaling of there is hard work being done to understand what's going to be best for the business, for our stakeholders, for the majority of our employees, potentially at a cost to some other employees. And we are working hard to solve this problem in every creative way that we can. But this happened not that long ago. We were sort of signaling this, and there's a board meeting coming up. We need to do the budget. We're having trouble balancing the budget, we're working through the options. And a very astute individual in an all company meeting said, does that mean that there could be another riff?

And we said, yes, it does mean, that is the very last lever that we would want to pull. And as of right now, we don't have concrete plans to do a riff, but if we cannot solve the budgetary problems other ways we could end up having a conversation about needing to do it. Right, that's the honest answer. But I think that would be a very difficult answer for a lot of leaders to give, because I do think that the other value, and it's a protection mechanism. You want to protect your team. These are the things that managers worry about so that employees don't have to worry about.

Daniel Stillman:

Yes.

Emily Levada:

And there's a desire to shield your team from uncertainty and from ambiguity because it makes it easier for them to do their jobs. It provides a sense of clarity and stability and all of those things, which we value. But I think there's some line where you can go too far.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. Yes.

Emily Levada:

In that direction, into a false sense of clarity and civility, which then ultimately ends up feeling like a lie after the fact.

Daniel Stillman:

Yes. Okay. So this is great. I think we're where I was hoping we would get to, because one of the tools that I was actually really excited to do a whole other interview with you about is, this idea of polarity mapping as a leadership skill, having to manage paradox as a leadership skill. And I think you've identified the paradox and the two by two of this tool and people can Google it, I'll put a link in, but it's like, we have these two values and plus and minus of both of them, because both values have goodness in them.

And over-indexing on them, over to the negation of the other creates dysfunction. So if we're talking about protection and transparency as two values where it's like I want to protect them, but I also want to be transparent, what I'm hearing is, I want to protect them because what's good about this, I want to shield them from things they don't need to know about because I want them to be able to focus on doing their job and creating value. And I want to give them transparency because I want them to build trust. And if I over-index on either of those, I can get anxiety and panic, I think, is what we're talking about.

Emily Levada:

Yes.

Daniel Stillman:

And so you're kind of just... Go ahead.

Emily Levada:

By the way, I mean this polarity exists in everyday management all the time. You hear this all the time, the leader, your employees, let's say you come to them and you say, I've made this decision. We've had this discussion, I've made this decision. They get upset because they want it to be included in the discussion and the decision. But when you come to them and say, I have this big problem and I don't really know the answer and I want you to help me figure it out, then they feel like you're not giving them enough clarity in the direction that you're providing. And this trade off between, what is the right moment to bring employees something that is clear enough that they feel they can understand it, they can run with it, but transparent enough in the sort of sausage making of it that they don't feel blindsided by the decision. And I think this is just a very amplified version of that polarity.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. Because I think I've definitely been in situations where leaders have over-indexed on protection and everything's going to be fine because they really believe that they're going to pull the fat out of the fire and they don't. And it comes as a serious whiplash. And I think what we're positing here is the negative emotions that come as a result of over-indexing on protection. People are thinking about now, in protection and people are maybe not thinking so much about, and then after, with protection, and they're on reduction of harm now and not long-term management of organizational emotions. So maybe, sorry, is there more that you want to?

Emily Levada:

No, go ahead.

Daniel Stillman:

Well, because I think this is maybe an interesting place to, a lot of people resist dealing with negative emotions because they are uncomfortable. And for those of you, because there's no video for this, Emily just did a very deep nod that I felt that in my chest. You're like, yes. So do you want to talk about why it's important to learn how to navigate negative emotions and what's important about being able to lean into those?

Emily Levada:

Yeah, sure. I think there are also these misconceptions. I think a lot of managers think emotions, well, a lot of managers think emotions are inconvenient.

Daniel Stillman:

And sorry, that's not funny at all. Funny because that hurts.

Emily Levada:

Somehow a thing that they have to deal with, but not their responsibility, explicitly, not their responsibility. And also that emotions are only the realm of the individual and versus the realm of the team or the organization, which isn't to say that individuals don't have emotions, but I'm also interested in this sort of organizational emotion that the sort of team emotion and thinking about how you manage that. And I think the real reason why, I mean, what I'm interested in is, how do you create organizations that can move as quickly and effectively as possible towards the results they're trying to drive? And the framework that I use when thinking about this is basically focused around learning. The idea being that if you can learn effectively, you can do anything. You can sort of move into any new space. You can find value sort of anywhere, and you're sort of gated by your ability to learn what's going to be of value quickly.

But I find that that goes hand in hand with a bunch of other things that we care about, creativity and risk taking and resilience and a bunch of other things. And so how do we get our organizations and the individuals in our organizations into this headspace, into this mood, into this emotion where they can be focused, they can be in the zone, they can be resilient and optimistic. And my perspective is that there are sort of three major negative emotions that detract from our ability to do this effectively. Those are fear and anxiety, boredom and apathy.

And a lot of the reason that I have come to those three is they show up over and over again as you review organizational behavior work. And a lot of the frameworks that I've come to really love and to utilize in my day-today, you see these three emotions or versions of these three emotions show up over and over again. And at some point I've started to feel like, hey, look, a lot of what it takes to actually create the conditions for success in my team is about how do we manage anxiety, boredom, and apathy in the team. Because if you can manage those effectively, you can create a team context and a team environment where that learning and that creativity and that resilience is possible.

Daniel Stillman:

Yes. So my first follow up question for that is, in my book, I sort of posit that nobody has a conversation thermometer or speedometer, and yet somehow we all... Oh God, this is moving too slow. This is moving too fast, this conversation is too hot, this conversation is too cold. With what organ of you, do you feel like you detect that there is apathy, anxiety, or boredom in the team, right? Because we can feel a person-ish, that's empathy or mirror neurons, but how do you feel like you read that room, especially given the fact that maybe you aren't seeing them all together in one place at one time, very often, how are you reading what's going on?

Emily Levada:

So I do think to some extent for the people that I do interact with more frequently, there is relationship building and you just start to learn. You sort of know when someone's on and when they're off or when they're right, when they're nervous about something or whatever. And so there's some amount of that. I will say at the team level, it's much harder virtually. And I remember saying when we first went virtual that I felt like I had lost the sensory organ because there was so much observation in a team meeting of who's paying attention, who's disengaged, who's talking to who, who got excited physically by those ideas, or what were the hallway conversations that happened after a meeting?

I do think that it's possible, however, to read a fair amount of this based on the signals around what your team is outputting and also where the problems are cropping up. So for example, teams who are in apathy are just much less likely to actually deliver results, and they're much more likely to be engaged in conflict or miscommunication. And even your attempts at moving the team top down don't actually produce the results that you want, right?

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. Apathy is a kind of inertia.

Emily Levada:

Right. People who are bored tend to start... Boredom often goes hand in hand with your bureaucracy. And they'll often complain about, just, I didn't need to be in that. Why are we in so many meetings about things that we all already know? Or they start looking, they start job crafting, they're not feeling challenged enough, and so they start finding other things to do that aren't their actual job. And so it's a little bit of that, just so fear and anxiety tends to create, people tend to turtle, they stop sharing information as freely.

And so you can start to see some of those things in terms of where are the conflicts happening, what's getting escalated to you, which projects are actually moving and which ones aren't. And I think it's one of those things when you start paying attention, but sometimes you do have to get in and evaluate. You and I have talked about my trust and conversation framework, which actually happens to have these four emotions in it. And there are tools like that that you can go in, you can just say, okay, how's everybody feeling? Right? I think we've talked about doing icebreakers where you get into a room and you have everybody just draw a picture of how you're feeling and see what people come up with.

Daniel Stillman:

And if you wait until things are terrible to do that, that's a signal. So it's doing this regularly, really taking a reading.

Emily Levada:

We have a question on our employee pulse survey that is, I don't remember how it's worded, but it's like, what's your predominant feeling? Or how are you feeling most days? And the choices are fatigued, anxious, optimistic, something else, but they're basically synonyms of these things. And so you can get a pulse of, oh, this team is feeling this way, and that team's...

Daniel Stillman:

Yes. Now this is clearly a great reminder that regular one-on-ones done well are so important. I think somebody shared with me recently one of their favorite questions, which was like, are you overwhelmed, underwhelmed or whelmed in your job? And in a way, that's kind of what you're trying to get from that pulse survey. And you want to have a human response from your team members and be listening to how they're responding. So these are... Yeah, sorry. Go ahead.

Emily Levada:

And that's obviously particularly for direct reports and one-on-ones, that is also a skill and a conversation that you build over time. You can ask that question of anybody, even if it's your first day managing them, but you want to build a relationship where an employee walks into the room and says, I'm overwhelmed, or says, you know what? I've been really bored. Right? And where you can just have those conversations openly without having to go dig for that information.

Daniel Stillman:

And this is psychological safety, which is why it matters. And I want to loop us back to the question of, what we're trying to optimize for. And if I'm understanding you right, it's that if we can keep our team in the learning zone, they can adapt to anything. And what we're trying to optimize for is getting their creativity, both pre but also post layoff, that if we over index on protectionism and don't lean into managing and anticipating some of these negative emotions, especially when we're going to need it most after we've had a reduction in force and we want people to do more with less, we're not going to be able to get that creativity out of them if we've lost trust, if we've afraid of telling us what's really going on.

Emily Levada:

And you're always going to see a drop in productivity after layoff. Actually, you're going to see a drop in productivity after any major change of transition, not just a layoff. And the question is, how quickly do you get back? And I will say this is particularly important in roles and jobs and companies where there's a really high degree of uncertainty and complexity and ambiguity.

Daniel Stillman:

So most of them.

Emily Levada:

Right, so most of them, if you're making widgets, actually managing by fear might work just fine.

Daniel Stillman:

Fear and Fiat, all the apps, but we're talking about not, the other thing. You need to get the best of people.

Emily Levada:

But people cannot do creative knowledge work when they feel fear and anxiety and boredom. Those things are just incompatible.

Daniel Stillman:

So when we talk about driving resilience and creativity, how can we build our toolkits as leaders to set ourselves up for success pre layoff? And you've talked a little bit about this, but I think we could double stitch on it and then post to reduce that refractory period.

Emily Levada:

Yeah, I mean, I think the first and most important thing, and sometimes the hardest is developing this measurement piece to sort of know where your team is. And part of that is because you're going to do different things. If your team is bored versus your team is anxious, you're going to do different things to solve those problems. And so you kind of have to know where your team is. And so as we talked about, some of that can be individual, talking to people on your team. Some of that can be quantitative measures by doing surveys.

Some of it can be observation of what's not working, or what questions are people asking. And after our last layoff, I just did a listening tour that was, go talk to as many people as I can in three weeks from all across my organization at different levels and different functions and hear what people are saying and then try to distill down from there. And so I think that's the big one or the big first step is actually getting good at figuring out where your team is. And then there's basically two levers that you're going to pull.

One is creating better systems of accountability and challenging your team more. And the other is building psychological safety or trust with your team. And we could talk about when you do which things, but ultimately I think it comes down to having those two skill sets or those two tools in your toolkit.

Daniel Stillman:

So my follow-up is going back to a point you made earlier, sharing, being transparent about what some of the challenges are. It sounds like if you want to involve your team in helping you solve that challenge, share that challenge with them in a way that they can participate in that challenge.

Emily Levada:

Yeah, I think so. And certainly I think if you're running a large enough organization, at least tapping the middle management layer or the layer below you to say, hey, here's how I'm thinking about this. Here's what I see. This is what I think we need to be driving, because they're going to be right that much closer to all of the individual employees on ground.

Daniel Stillman:

So what do you feel like is the most effective way to pull the most effective lever for you?

Emily Levada:

Well, I think it depends on where your team is. I think in today's environment, it's sort of most likely that people are in... Sorry, that's my dog squeaking his squeaky toy.

Daniel Stillman:

What's amazing, Zoom has filtered so much of it out.

Emily Levada:

Okay. Good. Can you not hear him squeaking?

Daniel Stillman:

I think I can. I'm aware that he's really got his jaws around that, but I'm cool with it. It's not showing that bad.

Emily Levada:

Okay.

Daniel Stillman:

I think they know that we're talking about them right now. He just looked up. It's like, me?

Emily Levada:

Okay, sorry. What was it?

Daniel Stillman:

No, it's all good. We're talking about where most people are right now is, there's a lot of fear.

Emily Levada:

Where most people are right now is either sort of apathy or anxiety. And I say that because those are the two states where you don't have psychological safety, and that lack of psychological safety is going to get you into one of those places. The difference is that in anxiety, the thing that creates anxiety over apathy is actually the high expectation. There's an expectation to do something, to be accountable for something. And there's some fear that if I don't do my job effectively, I'm going to be held accountable. With apathy, you actually have that fear, you're like, whatever. I can do this job in my sleep. I don't need to worry. Or who cares?

Daniel Stillman:

It doesn't really matter.

Emily Levada:

And so the important thing to do is, in that sort of apathy state is actually, I mean, the first thing to do is actually to drive that accountability. And when I say accountability, I don't necessarily mean if you don't hit X number, you're going to get fired. I mean, that sense of ownership and that sense of urgency, that little bit of stress that makes you really productive.

Daniel Stillman:

The dog requires attention. But it seems like you're also asking us to give people, it seems like in a way, the antidote to apathy is engagement, giving people things that they are truly excited about, that matter most to them, where they feel like they're impactful.

Emily Levada:

Yes. And I think sometimes that looks like a challenge, it looks like saying, hey, I have high expectations of you, and I believe you can meet those expectations, and I'm challenging you to do this thing, to own this thing, to deliver this result. And oftentimes, there are sometimes teams where that ownership actually isn't clear and people don't understand how their work connects to what the company is trying to accomplish. And so it is about how do you drive down to a discrete enough thing, an ask that feels like it's going to be meaningful and valuable and impactful and purposeful, because that's what people want. They want to feel that they're having an impact and having a purpose.

And that is going to challenge someone, right? Because ultimately, if you don't feel a little... Not really, not an exceedingly hard challenge, but that little bit of a challenge that makes someone sort of have to work. And I think that in some way, I know that's counterintuitive. If someone's feeling apathetic, give them more to do. But it's a little bit of this, it's easier to act your way into a new way of thinking than to think your way into a new way of acting kind of thing.

Daniel Stillman:

Wait, say that one more time.

Emily Levada:

It's easier to act your way into a new way of thinking than think your way into a new way of acting.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah.

Emily Levada:

Right?

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah.

Emily Levada:

Sometimes it is just doing of the task that gets us engaged, and sometimes it's hard to start. And apathy, as you said, apathy in many ways is an inertia problem. And it's like how do you break people out of that inertia? The challenge is when you do that with apathy, you're going to put people into the anxiety zone. And that in many ways is why people avoid doing it because they're not comfortable with this idea that they're going to do something that creates anxiety for their team. But anxiety is at least active. It's an active state instead of an inactive state.

Daniel Stillman:

So what's the value going back to our two by two? So the value of challenge can activate someone in a good way. It can give them a sense of, there's impact. We want to connect with what they're doing to not just output, but impact. And if we over-index on challenge, then people will just feel, we'll go back into that anxiety zone.

Emily Levada:

I think that's right. And I think also there's an underlying value here, which is maybe not in a polarity, but which is as a leader, in order to do this effectively, in order to create effective accountability for that team, you actually have to get your shit together.

Daniel Stillman:

You want to break that down for us a little bit?

Emily Levada:

You have to understand how that person's job connects to the company goals. You have to be aligned on what you're trying to accomplish. You have to set an appropriate metric or measurement for that person to hit. You have to be able to articulate to them with clarity what success looks like.

Daniel Stillman:

Yes.

Emily Levada:

And a whole bunch of things that sometimes managers are not good at, but it's a good opportunity to say, oh, this is what my team needs from me, and therefore this is what I should focus on in creating this accountability and this productive pressure.

Daniel Stillman:

Productive pressure. And that's a very delicate guiding because on one hand... Yeah, go ahead.

Emily Levada:

Well, and so then there's the second lever, which is it was just creating psychological safety. And that is the lever you need to pull when your team is in the anxiety zone. And I say it that way in that sort of order because I find if you have a team that's apathetic, it's sort of easier to get them moving, to be doing and to see results. That makes it a lot easier to then build psychological safety and trust. It's much harder to build psychological safety and trust in this sort of inactive state.

Daniel Stillman:

Why is that? There's some things bubbling up for me, but I'm curious, why do you think that is the case?

Emily Levada:

Yeah. I think that some of it is just people are not as receptive to it. And some of that is just, they're just not engaged in the conversations. It's something about doing the work that creates the context for the conversations that help us build trust, where we can get into a room and say, okay, why is it that you care about this? Or why do you want to do it this way? The work gives us a context or content for the conversations which help us build trust. Does that make sense?

Daniel Stillman:

It does. I also think conversations are about feedback loops. And certainly when we're talking about organizational emotions, I think of a one-on-one conversation as like it's here, you and I are talking one-on-one, but an organizational emotion and an organizational conversation is this longer amplitude, and it requires time to know what's happening. And so you have to get things moving in order to have a feedback loop. There's no feedback loop-

Emily Levada:

And presumably you can pull these levers at the same time, but the trust building's going to take longer.

Daniel Stillman:

Yes.

Emily Levada:

And so it's actually not a bad thing if you see your team moving from apathy to anxiety. You just need to know that in both of those cases, you're living a world where you don't have enough psychological safety. And that should be then the focus. And the other thing that I see people make a mistake on, is they see a team has this high accountability and is feeling fear and is feeling anxiety, and they're worried about what's going to happen if we don't do our jobs effectively, or there's going to be another layoff or there's going to whatever. And some leaders' instinct is actually to pull back on the level of challenge that they're giving their team, that somehow they believe that psychological safety involves going easier.

Daniel Stillman:

But.

Emily Levada:

But it's not really what it means. Psychological safety is about creating an environment where we can have productive conflict and where all of the voices and opinions are heard, and we can be proactive about resolving problems, it's not the same thing. Now, that doesn't mean that you might not be overworking your people, and you might need to pull back a little, but if you create psychological safety, then you have a scenario where someone can come to you and say, "Hey, I have too much on my plate, and can we talk about what the most important things to do are?" Or they can go to a stakeholder and they say, "Hey, you made this ask to me, but I really don't think that's going to be the most important thing for us to do to our customer." We talk through that.

Daniel Stillman:

And you want people to be able to say that to you.

Emily Levada:

You want people to be able to do that. And if you, as a manager, again, getting back to protection versus some other value, if you try to protect them by just taking things off their plate, you're actually not creating the ability for them to get into this place where they're really doing this productive, constructive problem solving that delivers the most possible value.

Daniel Stillman:

And the hope is, the belief is, that people want to do the best work of their lives. I think there's this implicit assumption and the idea of psychological safety that if we produce the right amount of productive pressure and hire well and create the right context, people want to do great work.

Emily Levada:

Yes.

Daniel Stillman:

I know.

Emily Levada:

Yeah. Yes, you are right. People do want to do great work, and great work requires ambitious goals, and it requires conflict. It requires working through difficult things. I don't know, great things don't come easily.

Daniel Stillman:

No, they do not. Then they would be common. And in a way, I'm looking at apathy and fear and creating clarity and creating productive pressure is your way of getting people out of the apathy zone and to get them activated.

Emily Levada:

Right?

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. So I mean, it's crazy. The time goes so fast. What have we not talked about that we should talk about? What have I not asked you that we should have asked you?

Emily Levada:

Well, I think just going back to the beginning, I think it's important to recognize when you do a layoff, that you're going to see fear and apathy, and it's maybe boredom. It's less common. It can happen. And the thing I think is important to stress is that, I mean, not only is seeing those things as normal and natural, but it's a thing that a manager can actively address in the way that they approach the team. It's not just the thing that happens to them that they have to wait for it to go away. And it's also incredibly unnatural after a layoff to say, oh, the thing I should be focused on is putting pressure on my team. And I think that learning, getting comfortable with this idea that there's a certain type of production pressure that allows the team to move forward and to feel like they understand that impact that they're having, they see results, and that allows them to create a context in which they can build back trust and psychological safety, actually gets you to where you want to be faster.

Daniel Stillman:

And that before, during, and after one of these events, knowing that they're coming, one of the things I heard you say is, get your shit together. The job of knowing what's going on with your team will determine which approach to use to get the most out of them.

Emily Levada:

I think-

Daniel Stillman:

And to create the best context for them to work through this.

Emily Levada:

Yeah, I think that's right. And again, to what we're talking about before, I think there's also a lot you can do before and during the process that helps you get there faster, right? Yeah. I mean, obviously I'm not helping former employees find jobs just because it creates psychological safety. I'm doing it because it's the right thing to do. And because I think they're amazing performers, and I want to see them be successful, and I would never have wanted to cut them for my team in a different situation. But it does help to be able to authentically say, this is why we are where we are. This is why we made the decisions. And by the way, we really believe, even though we've let these people go, we want to see them be successful, we want to help them. We're going to do right by them in the ways that we can. Those things all do contribute to your ability to build trust and psychological safety as quickly as possible back with the team that is still in this.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. You can't withdraw from the bank of psychological safety if you haven't invested in it.

Emily Levada:

That's true. And you also can't just hide and pretend that it didn't happen.

Daniel Stillman:

No. So I think the surprising bit of feedback from this is that post layoff, if I've set myself up for success, well, and there is psychological safety, creating positive pressure post layoff may be the most unexpected move to make.

Emily Levada:

Yeah. I mean, in a world where you did have psychological safety, I think what you would most likely see is boredom. Because basically the boredom happens in a world where you have psychological safety, but people aren't really sure what to do. They don't feel challenged.

Daniel Stillman:

Yes.

Emily Levada:

Oh, they don't have alignment. They don't know which direction to go. And so being able to sort of step in and say, focus on this thing, run in this direction. Here's the expectation, I'm setting a high bar. Actually, it creates that forward movement that is self-reinforcing.

Daniel Stillman:

So when will we have you on for a three-peat to talk about your book? Because you're just in the early stages, right?

Emily Levada:

Yeah, we are in the early stages. I don't know. I'll let you know.

Daniel Stillman:

Okay. That's a strong commitment. It's a challenging and emotional process. I'm glad you're working with someone.

Emily Levada:

Thanks.

Daniel Stillman:

I have someone I had on this podcast a while ago who talked, describes your work as being a book doula, and I think it's a very apt metaphor.

Emily Levada:

Yeah. This book has been rattling around in my head for seven years, and so it feels great to finally start getting some of it out into the world.

Daniel Stillman:

I'm really excited to see it real. In the meantime, how should people interact with you post this conversation? If they want to stay in the loop about all the things Emily Levada, how are they to do it?

Emily Levada:

Yeah. The best way is probably on LinkedIn. That's where I'm the most sort of active and plugged in.

Daniel Stillman:

Yes.

Emily Levada:

Nowadays.

Daniel Stillman:

Hit that follow button on LinkedIn. I hope you have that as your first.

Emily Levada:

I do.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. As your default action. Well, good God. An hour is barely enough time to scratch the surface of this topic, but I really appreciate your generosity in working through some of these questions, and I know that there's a lot of goodness in this. So thank you so much for this time.

Emily Levada:

Thank you for having me.

Daniel Stillman:

Well, we'll just call scene then if we feel complete.

Emily Levada:

Yes.

Daniel Stillman:

And we are complete.