My guest today is James Rutter, Chief Creative Officer at COOK, the pioneering frozen food company, where he oversees internal and external branding and communications. COOK is a founding UK B Corp, committed to using its business as a force for good in society, and has been ranked in the top 100 Best Companies To Work For every year since 2013. COOK’s award-winning frozen meals and puddings (which are desserts, btw) are made by hand in Kent and Somerset, and sold from 98 of its own shops nationwide, in 950 concessions and through its own home delivery service.

James joined COOK in 2010 after 15 years as a financial journalist and editor, and he speaks and writes regularly about purpose-driven business and brands. You should really follow him on LinkedIn!

James and I talk about the glory that is a proper Fish Pie, and about citizenship and participation. James’ leadership philosophy for his internal team is grounded in a sense of play and a recognition of community.

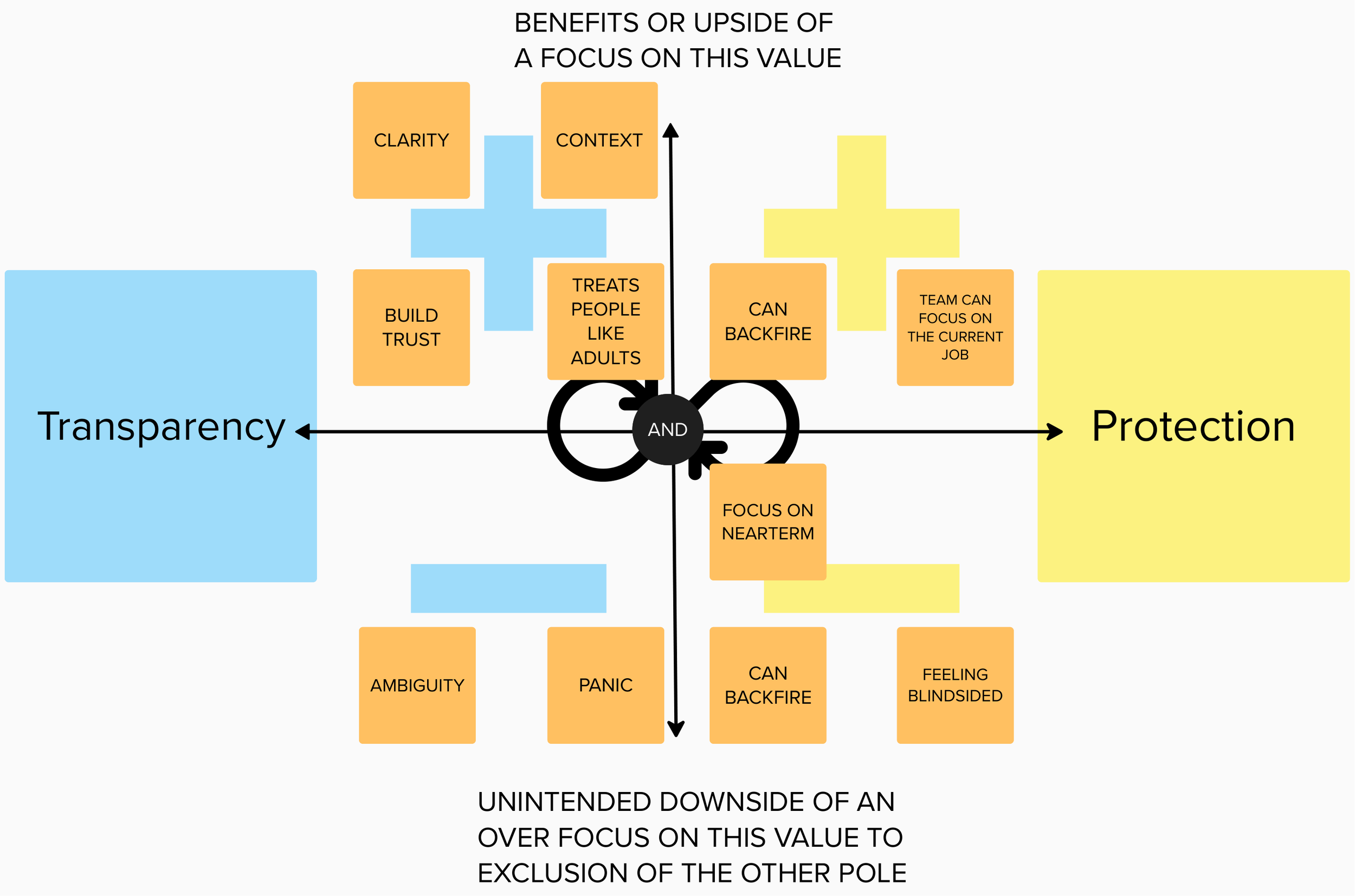

He shares some of his favorite insights from Peter Block’s book, "Community: The Structure of Belonging" and the deep value he’s found in working with Jon Alexander on Citizenship and Participation. Jon Alexander is the author of the bestselling book, "Citizens." James references Jon Alexander’s Participation Premium Equation in the opening quote.

There is so much goodness in this episode!

At Minute 27 James shares his community and transformation insights from Peter Block, including the essential idea that a small group, a community, is the fundamental unit of change, especially when that group is grounded in possibility. He also goes to share the impact that Block’s ideas of Inversion have had on him:

As James says, summarizing Block:

“It's not the performer who creates the performance, but the audience… And again, in a conversation sense… it's the listener who creates the conversation whereas we often think it's the speaker who creates the conversation… it's the child who creates the parent, not the parent who creates… this is (not) some kind of answer, but… a thought to play with. What if that's the way it works? How would you approach it differently? If the audience creates the performance, then how are you seeking to bring the audience into it? How are you giving them the power?”

At Minute 42 we discuss the importance of Connection over content:

“...you've got to seek to build the human bonds first before you seek to do whatever the worky thing is you want to do.”

In essence, we are marinating in Danny Meyer’s ideas of an Employee-First workplace, which is why we talk, at the end of the episode, about how Happy Cooks make Happy Food, referencing an earlier conversation we had.

And James insisted on talking about my Mom being on the Mike Douglas show with John Lennon, Yoko Ono and Chuck Berry in 1972, hosting a historical cooking segment - this episode is famous because it’s the first time John and Chuck met and Played together. You can see A Tiny Video Clip of my mom on TV here (most of them seem to get pulled down). At a crucial moment in the cooking segment, my mother, just 22 and not actually my mother yet (or anyone’s!) realized that the studio band was playing chaotic music, and that everyone was in a chaotic space, and she announced that unless we had a calm, peaceful environment, the food would taste chaotic - our intention and our energy would flow into the food. The Host, Mike Douglas, asked the band to play something quieter and more mellow, and John Lennon, assigned to cut cabbage, began reciting the mantra he wanted to suffuse the food:

“Rock n Roll…Rock n Roll…Rock n Roll”

What do YOU want to suffuse your work with?

Links, Quotes, Notes, and Resources

Peter Block on Community: The Structure of Belonging

Jon’s Agency Equation: A Proposal

Agency = Purpose + Belonging + Power

Agency: the ability to shape the context of one’s life

Purpose: the belief that there is something beyond your immediate self that matters

Belonging: the belief that there is a context to which you matter in turn

Power: practical access to genuine opportunities to shape that context

Exit, Voice, Loyalty: An essential book on people and organizations

Finding flourishing and play at work - inspiration in https://www.punchdrunk.com/work/

Quotes no one said: “Teach Them to Yearn for the Vast and Endless Sea”

Via quote investigator: https://quoteinvestigator.com/2015/08/25/sea/

Matt LeMay on Agile Conversations

Happy Cooks make happy food: On Daniel’s Mom being on the Mike Douglas show with John Lennon, Yoko Ono and Chuck Berry Hosting a cooking segment: Context and History!

Why this episode is famous - it’s the first time John and Chuck met and Played together.

A Tiny Video Clip of my mom on TV! (most of them seem to get pulled down)

Key Quotes

Min 27 “If we're seeking to…restore community, then people have to come together and have a conversation about what's possible, not be anchored on what the problem is, what the solution it is that needs to be found to the problem, what power needs to be exerted to make things work better, but to be open minded to the possibility of what they can create together. And that ultimately that is where community drives from…the unit of transformation is a small group.”

Min 29 “I think you might like this idea as well from this community book, which is about inversion…inversion in terms of thinking about: It's not the performer who creates the performance, but the audience…And again, in a conversation sense… it's the listener who creates the conversation whereas we often think it's the speaker who creates the conversation. He says it's the child who creates the parent, not the parent who creates. I think there's some really interesting kind of. That's not meant to say this is some kind of answer, but it's just a thought to play with. What if that's the way it works? How would you approach it differently? If the audience creates the performance, then how are you seeking to bring the audience into it? How are you giving them the power?”

Min 42 “I do think that in this kind of “be an overnight success, kind of move on, climb the career ladder, have a million jobs in ten years” type vibe. People overlook the real value of established teams and what teams that work together for a long time can really deliver and achieve. Because that's when you do get really high trust. You do get a sense that people turn up and are much more open, are much more willing to be vulnerable. It's human nature. We're not prepared to risk so much with people we don't know so well. If you want people to come and take the mask off, you've got to seek to build the human bonds first before you seek to do whatever the worky thing is you want to do.”

Min 49 “Genuinely, I think the more time we collectively spend thinking about how we are together within our organizations, our businesses… The more productive we're going to be…fulfilled…the more we're going to feel able to take those masks off and be who we genuinely are together and hopefully help each other into a kind of more flourishing future.”

AI Summary and Key Moments

James Rutter and Daniel Stillman discuss creating a sense of community and enabling creativity throughout an organization, with a focus on giving everyone a voice and establishing trust.

They also talk about the power of playfulness in leadership and the value of established teams and long-term relationships in achieving high trust and vulnerability. James emphasizes the importance of starting with people and their relationships in organizations to create a great product.

Key Points

James explains the importance of giving everyone a voice and creating a sense of community at a diverse workplace with 1800 employees (3:43)

James and Daniel discuss the importance of human flourishing and how it relates to creating a sense of community and enabling creativity throughout an organization (5:56)

James discusses the challenge of enabling people working in a factory to flourish and how their company provides benefits and opportunities for growth (8:30)

James discusses the importance of individuals seeing their own impact on the world and how their company tries to bring that to life through initiatives like care cards for retail teams (12:48)

James shares a story of a customer who received a care card and how it made him feel seen and recognized, highlighting the impact of creativity at an organizational level. (14:10)

The company runs a program called Raw Talent that trains and employs people who have been in prison, homeless, or dealing with addiction or mental health problems (17:15)

James talks about giving everyone a voice and pushing them out of their comfort zones to create creative tension, and mentions an impactful session they had with immersive theater group Punch Drunk. (32:17)

They discuss the atomic unit of change - conversations - and how they can create alignment within a group, and James talks about his role as Chief Creative Officer in holding space for creative team conversations (37:55)

James suggests that building human connections and establishing trust is key to creating an environment where people feel safe to be themselves and take off their masks. He also emphasizes the value of established teams in achieving high levels of trust and vulnerability. (41:05)

More About James Rutter

James is chief creative officer at COOK, the pioneering frozen food company, overseeing internal and external branding and communications. He joined COOK in 2010 after 15 years as a financial journalist and editor. COOK is a founding UK B Corp, committed to using its business as a force for good in society, and has been ranked in the top 100 Best Companies To Work For every year since 2013. COOK’s award-winning, frozen meals and puddings are made by hand in Kent and Somerset, and sold from 98 of its own shops nationwide, in 950 concessions and through its own home delivery service. James speaks and writes regularly about purpose-driven business and brands.

Full AI-Generated Transcript

Daniel Stillman 00:01

I will now officially welcome you to the conversation factory. James, I actually am really pleased that all of our conversations have led to this next conversation, because I've learned so much from you, not only the joys of fish pie.

James Rutter 00:21

You're going to have to explain that to everybody a bit later.

Daniel Stillman 00:24

Yeah. Yes.

James Rutter 00:25

Recipe in the show notes.

Daniel Stillman 00:26

Is that what you meant to say? Yeah. Well, I'm still waiting for the official recipe.

James Rutter 00:31

I've kind of, like, send you the official recipe.

Daniel Stillman 00:34

I've had to hack it together, but I was trying to make a low carb version, so I use solariac and anyway, let's just start with fish pie, because this is a great example of culture, because I think we talked about this in our last conversation. Many of the recipes for fish pie just sort of assume that I live in Britain because it's a very british dish, and they say, oh, go to your shop and get a fish pie frozen mix, which includes various types of fish, and then bang some peas and carrots and what, and then everything that comes out. Those are all things I knew about. I was like, what kind of fish is in a fish pie? No one could really explain. It took me a lot of research to try and pierce the veil of the cultural chasm separating England and America, which was shocking.

James Rutter 01:23

Yeah. Two nations divided by a common language. And fish pie.

Daniel Stillman 01:26

There you go, fish pie. Exactly. So maybe you can put yourself in context. What on earth does a chief creative officer do and where do you do it and why?

James Rutter 01:39

Gosh, I don't know what a chief creative officer should do, but what I do is an entirely, probably different kettle of fish. Back on fish. So I was thinking about this the other day, actually, because people always ask me and I usually just kind of shrug and I said, yeah, it sounds good, doesn't it? I'll tell you when I know what it means, but I kind of just stretch across a lot of things from the obvious, I guess, brand marketing type of creative stuff that probably springs to mind when people think of chief creative officer type roles and then into kind of strategy. And for cook, a lot of internal kind of comms, a lot of internal culture work.

Daniel Stillman 02:28

Yeah.

James Rutter 02:28

So I try and help other people be more creative in their roles rather than assume the crown of creativity, as it were, hopefully. Anyway, that's what I do. And so I try and kind of nudge, facilitate, as you would like to say, no doubt, and generally encourage people to be more creative in whatever they're doing at cook. That's how I like to think of it. Whether I accomplish that or not is another matter entirely.

Daniel Stillman 02:59

Well, we can have one of your employees on.

James Rutter 03:01

Yeah, exactly.

Daniel Stillman 03:03

How do you determine whether or not, I mean, we were talking a little bit before we started around some of the things you're learning around community and thinking of work as a community and bringing a citizen lens. You're really intentionally trying to craft what I would sort of describe as like this cloud of conversations, rivers and valleys of conversations between everyone that eventually lead them to become more creative but also more connected. How are you thinking about the ways in which you're trying to design the conversation at work differently?

James Rutter 03:43

I think

James Rutter 03:48

the obvious thing is that we try or we seek to just give everybody a voice, and that sounds blindingly obvious, I guess. And yet is often in any larger workplace, and we have 1800 people, which obviously is small by some standards, but very big by others, but across 1800 people working all around the country because we got getting on for 100 shops or 100 small retail outlets. So we got kind of 700 people in that kind of context. We've got another 700 people in a kind of classic blue collar manufacturing context in three different sites, four different sites. And then we've got kind of a central office in a classic office type environment. So seeking to give everybody a voice across that incredibly diverse workplace is actually really difficult. Yeah, I wouldn't say we achieve it all the time. Some of the time I really hope we do. But in terms of conversations and connections and relationships, which is what we use relationships as our kind of catch all for human connection, whereas you would go with conversation. But in terms of relationships, that's what we're seeking to. We're seeking to help everybody feel that they have strong relationships with their colleagues, but also with people in other parts of the business, that they have a voice and that they are therefore part of a community rather than a corporation.

Daniel Stillman 05:33

What's important about that shift you mentioned you're reading Peter Block's book on community. What are you learning in that book that's sort of shifting how you shape community? And why is it important to get to that place where people feel like this is a community and not just work, not just a job? It's not just fish pie.

James Rutter 05:56

Yeah, right. I think a lot of this comes down to a little bit. What do you believe about people and human flourishing? In a way? What's the point of it all? Carl? We're going deep early. Daniel.

Daniel Stillman 06:12

Why? Let's go there.

James Rutter 06:14

Yeah.

Daniel Stillman 06:14

Eudemonia is one of my favorite words. That is the greek term for

Daniel Stillman 06:22

the highest state for a person, right? The tippy top of Maslow's hierarchy. Flourishing.

James Rutter 06:28

Yeah, absolutely. And I think there's that sense in which all any of us can hope for is to achieve flourishing however you want to define it. And therefore, when we come together in a workplace, if that experience, if that collection of people isn't helping us move in whatever small way towards our idea of flourishing, then really what's the point? And so when you think about all a business is, at the end of the day, is a bunch of people coming together to do something collectively that they couldn't do on their own. That's all it is. It's a fiction. Otherwise, it doesn't really exist, other than those people's willingness to come together and do stuff. And so when we're together, when we're in the same room or over a call like this, or we're in a shop or in a kind of kitchen, in our respects, what we do there together has got to feel like it's both worth something to us, individually and collectively, and is somehow helping us progress. Baby steps, it might be towards our idea of flourishing.

Daniel Stillman 07:44

Yeah.

James Rutter 07:45

So that's kind of, I think, where it comes from a little bit is that belief in what we should be striving for as people. And how can we enable that, not just for the people up at the top of the pyramid, but for actually everybody in the organization.

Daniel Stillman 08:02

Yeah. So how does creativity and community look different throughout the organization? How do you approach giving everyone a voice and making everyone feel connected and creative? There's like the coal face, as it were, which is maybe the worst. Absolutely right. And then there's communications. There's the people who are wearing different colored collars, as it were.

James Rutter 08:30

Yeah, right. Absolutely. And I think that's one of the biggest challenges and kind of struggle sometimes I have with our ambition, when you take it down to a root level, that we have people working in what most people will call a factory. We never call it a factory. It is a kitchen. But people would see it and say, that looks like a lot like a factory. And they're working in what you might say is a production line, an assembly line. They're doing a pretty repetitive manual task. How can we possibly say that we're enabling those people to flourish? Is kind of a bad day. Look at that kind of context. And then, if you like a good day, look at that context is okay. We've got these people in a room. They got smiles on their faces. They're talking to their colleagues. They're having a laugh. They're getting paid enough to live on, which is really important. Yes. They get breaks when they get fed, they get some lovely little kind of benefits, which means they can use a free holiday home, because we got a little holiday home that they can go and stay in. They get together with their colleagues and they have some fun, and they actually, every so often, they look up and they feel part of a bigger whole, and they can say that. They can see that that's doing some good in the world. And so they feel a little prick of pride. And so when they go and meet their friends and they talk about their week at work and their friend just kind of moans on about the drudgery, they can say, oh, you know what? But we did this great thing as a business, or that we get free doctor's appointments or whatever it is. We get our birthday off little things, but they feel a little bit of pride about where they work, and they feel that actually they can stay there for a period of time, they can learn, they can grow, they can move on, they can achieve something that perhaps they didn't think was possible a few years ago.

Daniel Stillman 10:42

Yeah.

James Rutter 10:42

And so even at that level, I say even that's a very kind of condescending thing to say, but at that level, we are hopefully bringing the possibility of flourishing to people in a way that another company wouldn't.

Daniel Stillman 10:59

Yeah. Is some of that have to do know? I'm wondering how the narrative of the B Corp is held throughout the company, because you are a benefit corporation, and we can talk a little bit about what that means for those folks who maybe aren't familiar with it. Do the people throughout the organization understand what that means to be part of not just their own flourishing and organizational flourishing, but also societal flourishing, which is presumably part of what a benefit corporation is meant to.

James Rutter 11:42

Know, the B Corp movement. And again, this is a classic transatlantic divide. So whereas in the US, you have benefit corporations, which is a legal structure.

Daniel Stillman 11:57

Yes.

James Rutter 11:58

You then also still have certified B Corps, which is a certification, kind of an independent certification process that is different from being a benefit corporation.

Daniel Stillman 12:11

Right.

James Rutter 12:11

And over here in the UK, we only have certified B Corp, so we don't have a legal structure.

Daniel Stillman 12:17

Right. You're still whatever the equivalent of our S Corp or LLC is to the government, you look the same.

James Rutter 12:23

Yeah, to the government we look the same. We have to change some wording in terms of how we're incorporated, say we actually take people and planet into consideration, not just profit, when making any decision, but we're not in the same legal structure as us benefit corp people. But as a B Corp, certified B Corp, yeah, the whole kind of goal is using business as a force for good in society. Now, how many of our 1800 people know about that, buy into that, get up in the morning feeling good about that? I don't know. Hopefully some. Definitely not all, I would say, but certainly some. And I guess in all this realm, be it B Corp, be it talking about kind of higher purpose of business, however you want to frame it, I do think a lot of it comes down to your role, your job, what you do day to day, and how can you witness your impact on the world. So you're going to get some pride from what the organization does, but to really have a sense that what you are doing is contributing, I think everybody needs to see their own impact.

Daniel Stillman 13:37

Yes.

James Rutter 13:40

Over the years we've tried to bring that to life with people in a number of different ways, I guess. And like I say, it's often much easier if you're like my direct team in the marketing team and you're talking about all this wonderful stuff and posting stuff on social media and what have you. Or like I say, for somebody who's in more of a manufacturing environment, it's tough. For somebody who's on the shop floor in a retail environment, it's more difficult. Two of the things we've done that I think goes some way towards achieving that. For the retail teams,

James Rutter 14:15

every year we give them, if you like, two little cards, and these are called care cards. And care is one of, we have, we have core values, of course we do called essential ingredients, and care is one of those. And each of those cards gives the holder 30% off our food for a year. And they can give that card to whoever they like, who they think needs our food because they may have health problems or their spouse may have health problems, or they may be bereaved or struggling somehow. And it's just for that member of card to see somebody who thinks needs it and say, oh, here you go, have a card, take 30% off. And the story of that really brings us to life that that kind of has the desired effect was a guy just sent us in a letter just to say, I was in one of your shops and I'd rushed in and grabbed some food, got to the till, I said, could I come back and pick it up later? And I said, yeah, of course, because he had to get to the hospital for his wife's chemotherapy treatment because she had cancer and he had two young kids and they were screaming. He was trying to get out the store and said, don't worry. Don't worry at all. So he came back a couple of hours later to pick his food up, and they just presented him with this card. And he said in his little letter, I just had to leave the shop because I was really emotional and I didn't want to cry in public. And he said, it wasn't the fact that it gave me money off, it wasn't the discount. It was the fact that somebody had seen me in my moment of need and recognized that for that kind of shop team member, that is them witnessing their impact.

Daniel Stillman 16:03

Yes.

James Rutter 16:04

And thinking, actually, I'm doing a good.

Daniel Stillman 16:05

Thing in the world and being creative. That's an example of creativity being harnessed at an organizational level. And it's a lovely story. And honestly, I can hear how it hits you because you feel it telling.

James Rutter 16:22

It, and then it gets.

Daniel Stillman 16:25

The hope is that everyone who gets one of these care cards in the organization feels that narrative impact, that they get that story.

James Rutter 16:37

Yeah, absolutely. And again, I don't think maybe this speaks a little bit to the community idea as well. We can't direct people to kind of use the cards in that way. We are giving them the possibility of having that impact and feeling that emotional connection and going home with a warm glow that night. That's almost the most we can do. We can't force it, but we can say, look, here you go, if you want to step into that, and here's your opportunity.

Daniel Stillman 17:10

I mean, they can give it to their mom if they want.

James Rutter 17:12

Yeah, no, they can.

Daniel Stillman 17:13

Genuinely legitimate.

James Rutter 17:15

Yeah, no, they can. So on the shop side, there's that kind of thing. And then, if you like, on the kitchen side of things, we run what is now quite a big, long standing program of taking people who've been spent time in prison or homeless, dealing with addiction or mental health problems. And we have a program called raw talent that then gives them kind of two weeks of, kind of quite intensive training, and then at the end of that, the possibility of a job in the kitchen. And so we've now taken, I think, 150 people over the last seven years. And again, those people then go into work, and the people they work alongside who aren't from the program when it's most successful, they feel genuinely invested in those people's future, and they feel a real sense of responsibility, but also of impact when it works and equally when it doesn't work, they feel absolutely gutted if people leave. And again, the kind of story that brings that to life for me was when we first started doing this program about seven or eight years ago, I think one of the first people we took into the program had been convicted. I think it was either manslaughter or murder. Very long standing case. And we'd said at the start, look, of the first, particularly this is early days, we're not going to take in anybody who you might feel is going to be potentially risky for your team and one of the teams in the kitchen, I think our pastry team was particularly nervous about the program and a bit resistant to letting it happen, but had reluctantly agreed. So we were a bit worried about this guy going. But anyway, he had him. He'd met lots of people in the kitchen, so we thought, well, let's let it keep going. We'll see how it goes. And first day, he kind of turned up. And at their break, at lunch, he kind of went to sit in the canteen and he didn't have anything to eat for lunch. These are date. We feed everybody there. We didn't back then. And one of the women in the pastry team just noticed it. So the next day when he came in for lunch, she just came over and gave him a sandwich and said, I made this for you today, so you can eat it. And again, it's just that sense of human connection, of suddenly feeling like you're responsible for somebody else that you're taking an interest in and that actually you can help them through.

Daniel Stillman 19:51

I think it's lovely. And this is sparking my brain to ask you about the citizens book that you're reading and if what you're learning from that is shaping how you're shaping culture now and in the future.

James Rutter 20:12

This is from the Peter Block one.

Daniel Stillman 20:14

Well, so you mentioned also John Alexander's book Citizen.

James Rutter 20:17

There's two. There's community, peter block, and citizens. So John is a guy, he's a british guy. He speaks our language literally, so he knows what fish pie is. And he's got a little consultancy or a partnership called New Citizenship Project. And they've been going for a while working around this idea that we need to reclaim our sense of citizenship. So move beyond the sense in which we're a consumer and where our only sense of agency in the world is to consume something, to kind of give over our power to the corporations who are pushing stuff at us and say that's all we can do, and to actually reclaim our agency as citizens, to come together, to decide, to create, to kind of, I guess in conversation to your theme, kind of move ourselves forward and get out of this hole we're collectively in. And so a lot of their work, where we've kind of found the amount of value in working with them, is around this idea of participation and how to really resonate with people, with customers, you need to give them an opportunity not just to buy from you, but to buy into you and participate in what you're doing. And they've got a lovely little equation, which they call the participation premium, which is a higher purpose. So as a company, to have a higher purpose plus participation. That's right. I'm trying to remember how this equation works now. Higher purpose.

Daniel Stillman 22:10

I know.

James Rutter 22:11

Higher purpose plus something in return. So it's not to deny that actually, people kind of need to feel they get something from it. Times participation creates huge value. And so where we've been playing with that from a kind of customer facing side of things is, okay, so how can we give customers the opportunity to participate in a way that isn't just buying a product? What more can we do? So is there a conversation we can involve them? Can they somehow help us solve a problem? Can we invite them into a shop to somehow create something with us? I think that side of the citizens idea from a business perspective is really interesting. So how do you open your doors a little bit to participation and enable people to be more than just if you're, like a blind consumer of whatever it is you're doing?

Daniel Stillman 23:07

Yes. So this is really emergent for you. This is like something you're noodling on, how to make this real.

James Rutter 23:16

Yeah, completely. And a lot of it can just revolve around language.

James Rutter 23:27

So we do some kind of healthy kind of pot type of deal, dishes that are kind of for lunch. And so we had a promotion on. You can get three of these pots for ten pounds. So obviously that's one way you can just talk about it, save whatever, get three for ten pounds is a very obviously consumer driven way of talking about it. But you could reframe that language as kind of one for you and two for your friends, get together and eat. And so in a way that is just slightly taking people out of the. I'm just a consumer mentality into something that is more about, well, actually, this is enabling me to do something productive in the world. Does that make sense?

Daniel Stillman 24:17

It does. And it's a reframing. There's, like, this tiny axe in the back of my head that I need to grind because there's this famous quote. One of my favorite websites is this website called quote investigator. And very often people say, like, oh, there's this famous quote from so and so. And I'm like, they never said that. There's so many famous quotes that nobody ever said. And there's this famous quote that people think they attribute to Antoine Song. I can't pronounce his last name anymore. The guy who wrote the little Prince

James Rutter 24:49

The french guy.

Daniel Stillman 24:50

The french guy. And there's this quote that everyone attributes to him. It's like, if you wish to build a ship, do not divide men into teams and send them into the forest to cut wood. Instead, teach them to long for the vast and endless sea. It's a very beautiful quote, but unfortunately he never said it. And it's not really clear that anybody ever said it. But that doesn't mean that the idea isn't true. And even something as simple as, like, I think very often people think money is the lever to pull because it's very obvious and brutish. Lever, right? Like buy three, get one off. Right. I forgot the deal already. See, because it's not that important, it's not that impactful. But when you frame it as community, when you frame it as feeding your friends, when you frame it as gathering people together and potentially harness what comes out of that somehow, like, make people feel like they're sharing those stories that they are absolutely writing society, invite someone you don't agree with to dinner. These are ways of really being part of a very different conversation than we make food and it's affordable and we're making it slightly more affordable for you. And that is a very creative approach to changing the conversation about what it is that you do and what people would say it is that you.

James Rutter 26:21

So to my other book, I'm reading my community Peter block book, which I was saying earlier, he talks about community is a conversation around possibility.

Daniel Stillman 26:31

Can you say that one more time? Let's let that sink in. That's a really great. Community is a conversation around possibility.

James Rutter 26:40

Possibility, yeah.

Daniel Stillman 26:41

What on earth does that mean? Say more about that. That's beautiful.

James Rutter 26:45

I think his point is quite a big kind of mind expanding one. If we're seeking to. He talks about restore community, then people have to come together and have a conversation about what's possible, not be anchored on what the problem is, what the solution it is that needs to be found to the problem, what power needs to be exerted to make things work better, but to be open minded to the possibility of what they can create together. And that ultimately that is where community drives from. Yes, and he's got this again, there's lots of lovely little sentences, long quotes in this book.

James Rutter 27:41

I'm going to misquote this. But anyway. But the unit of transformation is a small group.

Daniel Stillman 27:46

Yeah.

James Rutter 27:48

And that immediately reminded me of that classic Margaret Mead quote. If she really said it, you can check.

Daniel Stillman 27:54

She did say it, but I'll double check.

James Rutter 27:58

Fact checking.

Daniel Stillman 27:59

Margaret Mead.

James Rutter 28:00

Yeah, exactly. That whole never doubt the ability of a small group of people to change. The world is what it ever has. And I think it's actually a really powerful idea around how do you bring together small groups that then can be kind of energized and create real ripples through a business, through society, through a community. And the power of small groups is really interesting.

Daniel Stillman 28:32

I think this is really.

James Rutter 28:34

How do we even get onto that?

Daniel Stillman 28:35

What were we doing? Well, we're talking about community and citizenship. Yeah.

James Rutter 28:39

Because I was going to say, I think you might like this idea as well from this community book, which is about inversion. So inversion in terms of thinking about. It's not the performer who creates the performance, but the audience.

Daniel Stillman 28:58

Yes.

James Rutter 28:59

And again, in a conversation sense. So it's the listener who creates the conversation whereas we often think it's the speaker who creates the conversation. He says it's the child who creates the parent, not the parent who creates. I think there's some really interesting kind of. That's not meant to say this is some kind of answer, but it's just a thought to play with. What if that's the way it works? How would you approach it differently?

Daniel Stillman 29:23

Right.

James Rutter 29:24

If the audience creates the performance, then how are you seeking to bring the audience into it? How are you giving them the power? How are you.

Daniel Stillman 29:32

Well, recognizing that they have the power?

James Rutter 29:35

Yeah.

Daniel Stillman 29:36

I recently had a guest on my friend Matt Lemay. We talked about his one page, 1 hour manifesto, which I will link to in the show notes where he just thinks teams should only any. Nobody should spend more than an hour working on anything longer than one page to share back with the team. Just to close the cycle of conversations. He has another talk that we unpacked in the conversation around. You don't get anyone to do anything because people come up to him after his talks and say, like, well, these are great principles about leadership. How do I get people to do this? And you're like, well, you don't get anyone to do anything. We invite them. We create the conditions for. We create a space for. They have the power. Yeah, the power is yours. That's a captain planet reference for those who understand. So I was thinking, when you're talking about the Margaret Mead quote it's really interesting to think about what the atomic unit of change is because obviously in my book I would assert that the unit of change is a conversation, and I think we can have a conversation with ourselves and we can have a conversation with another person to try and create a lime or whatever. But I agree that getting a group of people to have their vector maps instead of being everywhere, to being at least directionally the same, this is leadership. And I'm curious with your. We've talked about lots of spheres of conversation. We've been talking a lot about the big community, the organizational conversation and how it exists in different strata. I'm curious, in terms of your team, how do you see yourself as a designer of conversations, in terms of getting that group of people to discuss, deliberate, decide, any other ds that we can think of.

James Rutter 31:28

Explain more. Just what are you digging at?

Daniel Stillman 31:31

Well, because you are the chief creative officer, but I presume you don't operate by fiat. There is a group of people who discuss things together and say, ought we to do a, b or c, or should we take a plus b divided by c or none of the above. Right. The creativity at the creative team level, your creative team level, you're the one who's holding space for those conversations.

James Rutter 32:06

Yeah.

Daniel Stillman 32:07

How do you do it? What's your trick, assuming you're doing it well.

James Rutter 32:17

Do I have a trick? That's a good question.

Daniel Stillman 32:20

Well, I mean, there's no tricks, obviously, there's no tricks.

James Rutter 32:23

Again, I think

James Rutter 32:27

a lot of it does come back to giving everybody a voice, making sure people feel confident enough to use it, and then seeking to push them into places where they might feel a bit uncomfortable, because that's where the creative tension you hope, will really start to grip and move them forward.

James Rutter 33:04

I don't know if there's a trick, but one of the most impactful things I ever did was do a session with the theatre group called Punch Drunk. Have you ever come across punch drunk?

Daniel Stillman 33:20

No.

James Rutter 33:20

I know they've been to New York at times, so they do these incredibly grand, immersive theatre experiences. So they've got one on in London at the minute, which is all about the fall of Troy. And it's the kind of things where you queue up, everybody has to wear a mask, like a classic half face mask, masquerade type mask. It's usually really dark. You get let out at various places, usually in a big industrial type of site where it's very dark and you're just free to wander.

Daniel Stillman 34:01

Were these ones who made sleep no more?

James Rutter 34:04

Could well be. Was it sleep no more?

Daniel Stillman 34:06

It's because it's giant, because I remember wearing such a mask? And it must be running around early, early days when it was only supposed to run for. I'll just pull rank. It was only supposed to run for a month, and then they just kept doing it. But I think that may be them, and I feel like I should know that. But, yes, sorry, please proceed. Yeah, they totally did sleep no more. That's right. Because it's beyond immersive. It's in a warehouse and there's many, many scenes going on, and it's like beyond an escape room. Right.

James Rutter 34:42

The whole thing is just all going on. But they very cleverly guide and everybody to the same place, the denumont. So everybody experiences the same. So going back some years, I was lucky enough to do a session with them where they were just showing people mostly from kind of brand marketing, creative industry types, people, how they prepare their actors for the performance, some of the things they go through. What that just really brought home to me was the power of play, because it was all around, genuine play around, kind of very unstructured, kind of improvisational games, techniques with some loose rules and frameworks, but within which you were able to do kind of what you wanted, create scenes in your mind, write down kind of letters as if you were writing to somebody who was the thing in your head, all this kind of stuff. And then the best bit was when they open the set, they let everybody into the set one at a time, at two minute intervals. And the sets are always really dark and gloomy. And hidden around the set are candles, little candles, electronic. They were but little electric lights. And by each light is a task. And so when you get led into the set, they say, right, your job is not to be seen by anybody, so you're not allowed to be seen. And you've got to find as many tasks as you can and just do the task. And so you're let into this set and suddenly it comes flooding back to you. The experience of being a child playing hide and seek, and it being the most exhilarating experience in the world to be just in a little bundle in the corner with your heart beating and hoping the person who walks past isn't going to stop and see, and then finding this little light and opening up the paper and just reading what it says and without even thinking, just doing it. And so there was one that was like, sprint down the corridor behind you. There was another one that was pick up the mannequin and dance a waltz on the dance floor. And there's all these kind of things. And it was just such a powerful experience? Because it just reminded me that if you allow people to get beyond their tram lines, that they're told they've got to stay in and really kind of play and immerse themselves in what it really means to create your own experience, you then just ignite people's kind of imagination for what they can do.

Daniel Stillman 37:32

Yes.

James Rutter 37:35

I obviously don't do anything like punch drunk, but at least seek to have a little drop of that in every gathering.

Daniel Stillman 37:44

Yeah, but you brought your team out to something, to one of those, did I understand correctly?

James Rutter 37:51

No, this was me on my own, sadly. But I tried to bring it back. Yeah.

Daniel Stillman 37:58

How did you talk to me about that? Because you talked about giving everyone a voice and bringing in play and playfulness. How do you try and create the conditions for playfulness? In what ways are you trying to nourish your team so that they have the food, the materials to do it?

James Rutter 38:21

I'm a big lover of games, full stop.

James Rutter 38:28

And you see it with any group of people. You'll know this. You'll see it with any group of people, that you give them some silly little simple game to play.

James Rutter 38:41

I think I've seen a video of you doing, like, the shaky thing.

James Rutter 38:47

Anything like that. I think ones that involve pairs of people are particularly good. So if you can do anything that involves an interaction and is a little game,

James Rutter 38:59

you'll have done this thousands of times. You'll go from, like a quiet, dull, kind of slightly lethargic room into a room that's full of energy and laughter and possibility and what have you.

Daniel Stillman 39:11

Yes.

James Rutter 39:14

In that sense, I don't think it's rocket science. It's like figuring out ways to kind of ignite the playfulness that lies inside of all of us and to make people, oh, hey, it's okay. We're allowed. This is playtime.

Daniel Stillman 39:31

Yeah, I think it's beautiful. I have a very difficult question to ask you, and I'm not sure if I've been poking at something, and I don't even know how to ask this question, so I'll try. I'm thinking about the event that I invited you to, the leadership gathering. We were talking about difficult conversations and the sense that what I find often with people is when they're in a challenging context, there's one way that they want to be something that they want. There's ways that they think they ought to be or should be in the sense that we're angry or disappointed or frustrated, but we need to be calm or patient. We're nervous, but we feel like, we need to be confident. And I'm wondering for you as a leader, how you thread that needle. Because the reason I've been poking at this is I love this idea of everyone being themselves and feeling like we're safe to be ourselves. And I also get this sense from a lot of the clients that I coach of this idea of, like, I have to put this mask on, I have to be a certain way. And I've been really thinking about, well, how do we be the other ways and how do we do it in a way that feels good to us and good to the other people? And I imagine that in your work, it's not all play. There are some challenging conversations. I'm wondering how you sort of create a shift in yourself so that you can show up in the ways that you feel you need to in an authentic way.

James Rutter 41:05

I might throw this back as another question, because do you not think ultimately that's built on human connection? So it's very hard to come without a mask if I'm meeting you for the first time. It's just difficult. Some people maybe have that superpower that it's always out there and they just are who they are, but most of us will come with a little bit of a mask on because we're not quite sure how that connection is going to go, whether there's going to be any connection, whether we just miss each other on the way past type thing.

James Rutter 41:42

So finding ways to build that relationship in a personal way as quickly as you can, I guess, would be my sense of how you get then to a place where you're going to be comfortable to show your true self rather than your master. So.

James Rutter 42:08

So again, so in a kind of cook context, we're mostly very fortunate. People tend to stick around for a long time. So you build relationships over years. And I do think that in this kind of be an overnight success, kind of move on, climb the career ladder, have a million jobs in ten years type vibe. People overlook the real value of established teams and what teams that work together for a long time can really deliver and achieve. Because that's when you do get really high trust. You do get a sense that people turn up and are much more open, are much more willing to be vulnerable. It's human nature. We're not prepared to risk so much with people we don't know so well. If you want people to come and take the mask off, you've got to seek to build the human bonds first before you seek to do whatever the worky thing is you want to do.

Daniel Stillman 43:18

Yeah, that makes sense. That's really interesting. Thank you for. I appreciate that. It's a question I've been sort of scratching at for myself. I appreciate your perspective on it. Well, so listen, we're getting close to the end of our time together. My lord, the time goes fast. You are a delightful person to converse with, James. What's your secret? How do you do it? What? Haven't I asked you that? I ought to have asked you what? Haven't we talked about that you think we ought to have?

James Rutter 43:48

What should we have talked about? We've done a lot. Haven't we talked about inversion. Inversion of all that stuff. Citizenship, community.

James Rutter 44:03

We haven't talked about your mum. It's a well known story.

Daniel Stillman 44:08

It's not a generally well known story.

James Rutter 44:11

And it's such a great story.

Daniel Stillman 44:15

I.

James Rutter 44:16

Feel like, about the coolest mum story I think I might have ever heard.

Daniel Stillman 44:20

Well, could we put it in context? How did it come up and what was your experience of being like, oh, I should definitely look into this because I feel like we were talking about food and how happy cooks make happy food.

James Rutter 44:34

Exactly. It came up because that's exactly what we were talking about. We were talking about how happy cooks make happy food.

Daniel Stillman 44:41

Yes.

James Rutter 44:41

And that led us directly to your wonderful, glamorous mother, who came across like this celebrity tv chef before there even. Were celebrity tv chefs in 1973.

Daniel Stillman 44:57

I will put a link in the show notes. In 1972, I believe, less than a year before my brother was born, before my parents were married, my mother was invited to be a cook. She was a macrobiotic cook at the time, and she did a cooking segment with John Lennon, Yoko Ono and Chuck Berry on what was called the Mike Douglas show, which was like Donahue and Oprah of its day. And what was extraordinary, this is a very famous moment. John Lennon. Yokono agreed to come on the Mike Douglas show for a whole week with the caveat that they could bring any guests that they wanted and they were into macrobiotics. Although from the look of know, I think John was on a lot of heroin at the time. It didn't look like he'd eaten in weeks.

James Rutter 45:40

He was on more than your mum's onion cakes.

Daniel Stillman 45:43

Yes. Tajiki egg rolls. And what is quite delightful about is that many of us. I saw it for the first time when I was like 15 1415, where my mother got the video through. They offered her a tape of it and she was like, I'm never going to have a machine like this. My mother was somebody who'd given up her silverware because she thought she was going to eat with chopsticks for the rest of her life. But there was a still shot of John Lennon feeding my mother an egg roll, which happened between takes. And it was just sort of accepted, like, that's a thing that happened, but it is an extraordinary thing. And what's funny is that sometime in the think VH one had the whole week on because it was a very famous. They had lots and lots of famous people on the Mike Douglas show. And so people called my mother and they're like, hillary, are you on VH one? And now it's in. Actually, that bit is in the rock and roll hall of fame because it's the first time that John Lennon and Chuck Berry ever met and played together. You can find footage of that with Yoko ono ululating in the back. Should you care to engage. I just love that and that sound.

James Rutter 46:52

That would be my go to story for every social occasion ever.

Daniel Stillman 46:55

Let me. It does come up.

James Rutter 46:56

Mum, cook for John, Yoko.

Daniel Stillman 46:59

Right. But the point is, there's this moment where they're all. It's just kind of a cluster fuck. And my mother's like, we need to have a calm and peaceful environment, otherwise the food will taste very chaotic. And she just gives everyone a job. And they start playing very nice soft jazz. And so they're playing very weird, sort of like, very chaotic music. They chilled it down. I'm so glad you enjoyed it. Hanging out with my mother circa 1972. This is a very special time.

James Rutter 47:26

I love it. I encourage everybody to watch that clip and marvel over your glamorous mother.

Daniel Stillman 47:32

Oh, thank you. I really appreciate you giving my mom a shout out. She'll enjoy this episode a great deal. Well, besides that, anything else?

James Rutter 47:46

It literally says here, your mom.

Daniel Stillman 47:48

Yeah.

James Rutter 47:48

Rock and roll cabbage.

Daniel Stillman 47:49

Rock and roll. Yeah, that's what Sean Lennon was saying as he was cutting the cabbage. Rock and roll. Rock and roll. Rock and roll.

James Rutter 47:55

No, I mean, I guess the thing we didn't touch on, which maybe we said we would, which just to finish on it, because it's a little bit encapsulated and that good cooks make good food comment. This sense of, again, organizations working from in to out. And how actually, if you don't start with your people and their relationships or their conversations in your world.

Daniel Stillman 48:20

Yeah.

James Rutter 48:20

And how those are back again. Back. And if. And how those are promoting flourishing. How on earth can you hope to have a great product out of the world that's going to connect with the people you hope will be your customers?

James Rutter 48:34

Genuinely, I think the more time we collectively spend thinking about how we are together within our organizations, our businesses. The more productive we're going to be, the more kind of fulfilled we're going to feel, the more we're going to feel able to take those masks off and be who we genuinely are together and hopefully help each other into a kind of more flourishing future.

Daniel Stillman 49:02

What's not in that mike drop. You're right. So if you were to look back on all that we've discussed, and you were to give this talk, this conversation, a title, what would be the title of our conversation?

James Rutter 49:18

Rock and roll cabbage, surely.

Daniel Stillman 49:21

Rock and roll. Yeah, that's a good one. Rock and roll cabbage. Well, then I'll call scene.

Daniel Stillman 49:35

Thank you so much, James. This has been an absolute delight. I appreciate you making the time.

James Rutter 49:39

It's fun, yeah it was fun!