Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel PhD, is the Associate Director for Design Thinking for Social Impact, and Professor of Practice at the Taylor Center for Social Innovation and Design Thinking at Tulane University, where she teaches design thinking from an emancipatory perspective.

Design Thinking is a powerful set of tools and mindsets that can help people solve problems. But which people and which problems?

So first off, if you’re new to this conversation, design and design thinking can be racially biased, because people are racially biased. As Dr. Noel says in the opening quote I chose, most of us don’t understand our positionality - especially if you see yourself as “white”. It’s essential to see and understand what position are we looking *from* when we look *at* people and the problems we seek to solve for them.

Design is, in essence, making things better, on purpose, and it’s a fundamental human drive: To improve our situation by remaking our surroundings. But when we design for and with other people, the process becomes more complex.

So, you might not see yourself as a designer, but if you solve problems for other people or build systems that other people use to solve problems, you might be a designer in the broadest sense, or design thinker, even by accident.

So...you need to get serious and clear about how you learn about problems (ie, do research), frame them and solve them for others (ie, design - attempt to make something better on purpose).

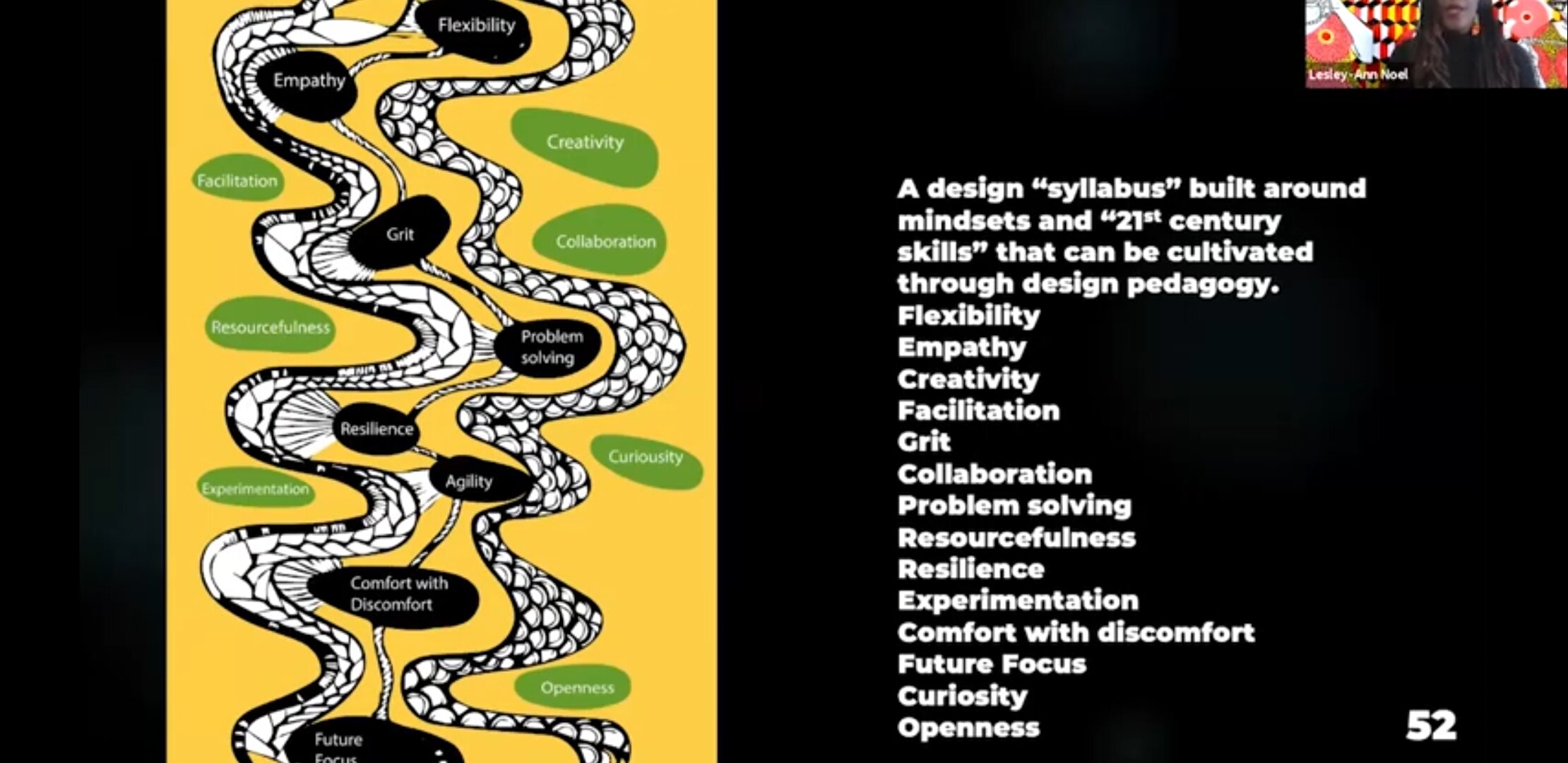

If you do see yourself as a Design Thinker, you might feel challenged by Dr. Noel’s reflections on Design Thinking, not as a set of Boxes to be ticked, but as a universe of different ways of thinking and knowing. Dr. Noel makes beautiful diagrams and models for the creative process that breaks out of the hexagons and double diamonds beautifully. I recommend checking out the screenshots I’ve taken of some of these models from her talks in the Links section

Another resource I suggest you dive into is Dr. Noel’s Positionality Worksheet, 12 Elements to help you and your team see the “water they’re swimming in.” You can also check out a Mural version I mocked up.

As Dr. Noel writes in her excellent Medium article “My Manifesto towards changing the conversation around race, equity and bias in design” it’s essential to start with positionality, for yourself and for your teams. That’s point one. Who are you in relation to the people you are working with and solving for?

Point Two of her manifesto is about seeing color, oppression, injustice and bias. For this I recommend getting a deck of her Designer’s Critical Alphabet cards on Etsy. They’re awesome!

Point 3 might surprise you: Dr. Noel suggests that we “Forget Diversity, Equity and Inclusion”...and instead embrace Pluriversality. DNI assumes an inside and an outside, an includer and the included. Pluriversality looks to remove the center and honors multiple ways of knowing and doing, each with its own valid center.

It’s nice to believe in a single ultimate truth for everyone...but that’s not going to happen. Pluriversality suggests that there are more than one or more than two kinds of ultimate reality. Pluriversality is essential for our time - finding a path forward together while respecting other’s paths and ways.

Pluriversality was a new term for me. I suggest you watch Dr. Noel’s talk at UC Davis on Embracing Pluriversal Design to learn more.

And I suggest you read the rest of her Manifesto for yourself!

I am thrilled to share Dr. Noel’s ideas on DeColonizing Design Thinking. It’s a critical conversation for our time. Design Thinking still has so much to offer the world if we are willing to lean into it and engage in dialogue with fresh and evergreen interpretations of it. People have been designing for as long as we’ve been people. Learning and respecting the pluriverse of Design Thinking in all cultures can deliver powerful progress.

Enjoy the conversation as much as I did.

Design Thinking as Curry:

DeColonizing our Bookshelves:

Using Mural to explore Positionality and Identity: A positionality worksheet More on that here

Slides from Dr. Noel’s talk on Pluriversal Design, illustrating many ways to visualize the design process.

The Designer’s Critical Alphabet...a powerful resource to check your biases as you create.

Minute 3

And then I started to see, well, okay. Actually as designers, design thinkers, whatever term you want to use. People who are creating the solutions, our positionality affects how we create a solution. Our positionality affects how we view the people that we're working with and sometimes we don't see our positionality. There are elements of our personality that become invisible and so I created that theme thinking of twelve elements that we might include in a positionality statement.

If we were writing research, I thought, how do we make this visible and interactive for people who are going to embark on a design process, right? So that we could see our positionality both individually and as a group and then understand how that impacts the work that we're doing throughout the process.

If we are to pick on white men as we always do, right? If we are a group of white men, let's say we are a group of six people working on this project. The idea was that after we went through this positionality exercise where we talk about race, gender, language, sexuality, ability status, social class, after we talk about all of this, we use the positionality wheel. It then becomes evident that, oh, our group actually does not have diversity in this area, or even if we're not talking about not having the diversity, at least we could see. Oh, actually, we all speak English only. And we are all upper middle class and we're doing this research with this group of people in New Orleans. How are we going to get a perspective? How are we going to be able to understand their perspective better when we are so different to them?

Minute 9

I actually was interested in that mass design surprisingly through a social lens because I always was thinking. Okay, well, how do we mass produce this thing to make it more accessible to people? But definitely, I have learned that diversity is very, very, very important focusing on the needs. Well, this is a human centered process that we really talk much more about today than when I left university focusing on the needs, the very specific needs of individuals that come up with design that then actually serves more people, I think is important.

Minute 11

And maybe about three years ago, I was in a design thinking space and someone told me, okay, well, here are the steps, you do this and then you do that. And I said, well, actually, I've been doing this for many years. And they're, yeah, but you have to follow these steps. And the thing is, I found that I was horrified that we had reached this space where people really felt that, okay, if you haven't checked off all of these boxes, you're not doing it right. When those of us who studied in the '90s and the '80s and I think, anytime before 2005, let's say, we were encouraged. Maybe we were shown different processes along the way, maybe each professor had a different model but we knew that we were going through a type of process that would get to an outcome at the end without learning those models.

Minute 38

Again, actually, I had a conversation yesterday where I was saying organizations actually need one or two angry people who are always going to be pushing you to make things better so you need to figure out, okay, where is this angry voice going to come from, right? Whether it's within the organization, or whether it's somebody from outside and that angry voice is going to push us a little bit, that little bit of dissatisfaction is going to push us to do things in different ways.

Minute 43

we just have to go through life with this openness and always this willingness to learn new things and understand new perspectives and talk with new people. The man who cuts my lawn, we normally have a good conversation on all that. We have just been talking and talking and talking about tips about gardening, right? And again, this all sounds random but it's not random. It's about how relationships with people help us to become, I guess, better designers.

Full Transcript

Daniel Stillman:

And I'm going to officially welcome you to the conversation factory, Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel. I'm so glad you're here.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Thank you, Daniel. Thanks for the invitation.

Daniel Stillman:

Thanks you for saying yes. Yes, and happy Friday. I don't know whenever anybody else is going to be listening to this, it probably won't be Friday. There's a one in seven chance that it is.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

It's always Friday.

Daniel Stillman:

But it's always Friday inside.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yes.

Daniel Stillman:

There's the question of where to start the conversation. I feel I have point one of yours from a talk you gave, which is that everything starts with positionality. I feel it's worth setting up your positionality however you'd like.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Okay. Yes. Well, thank you.

Daniel Stillman:

It's a broad question.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

No, it is a broad question and it's specific and thank you for noting that because I really do think that positionality is important. I start all of my classes with positionality so my positionality, I am a black woman from the Caribbean specifically from Trinidad and Tobago. I add to my positionality that I did undergrad in Brazil. Fortunately, the Brazilians haven't yet said, oh, she's stealing our identity because this is ... I left Brazil more than 20 years ago and I still consider myself very, very tied to that country. I do a lot of collaboration with Brazilians so I do consider that part of my positionality as well. I am a parent so I'm a mother of a 13-year-old boy. What else can I add to the ... I guess that's where I will leave it for now because sometimes in our positionality there are things that we want to share and there are things that we don't want to share. But the things that are most apparent are that I am someone from the African diaspora.

Daniel Stillman:

Yes.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Right. And then once I open my mouth, you say, okay, she has a different accent so I clear that up very quickly. I'm from Trinidad and Tobago. And I consider myself very much someone from the Americas, from the Caribbean and with this connection to Latin America.

Daniel Stillman:

Yes. Where do you ... There was an article, sorry. An exercise I saw the evidence of you running in one of your talks about Who Am I? in getting students. You're a professor of design thinking and so you teach this stuff to students all the time, when and where and why do you run this Who am I? exercise? Because I just saw the mural board and I can suspect I saw clusters and I wasn't sure if you put those gray bubbles there, or here, or where do you have this type of identity? And maybe you can just talk a little bit about when and how you run through that exercise with people because I think it's a really interesting and important one.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Okay. I have a PhD in design and the way I did my work is qualitatively. And so very often when you're doing quality to research, you have to start off with this positionality where you write a positionality statement and you say, well, okay, who am I?, so that the person who is reading the research will understand. Okay, if you think about me again, this person is a black woman from the Caribbean and that affects how she wrote this research. And then I started to see, well, okay. Actually as designers, design thinkers, whatever term you want to use. People who are creating the solutions, our positionality affects how we create a solution. Our positionality affects how we view the people that we're working with and sometimes we don't see our positionality.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

There are elements of our personality that become invisible and so I created that theme thinking of twelve elements that we might include in a positionality statement. If we were writing research, I thought, how do we make this visible and interactive for people who are going to embark on a design process, right? So that we could see our positionality both individually and as a group and then understand how that impacts the work that we're doing throughout the process. If we are to pick on white men as we always do, right?

Daniel Stillman:

It's totally fine.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

If we are a group of white men, let's say we are a group of six people working on this project. The idea was that after we went through this positionality exercise where we talk about race, gender, language, sexuality, ability status, social class, after we talk about all of this, we use the positionality wheel. It then becomes evident that, oh, our group actually does not have diversity in this area, or even if we're not talking about not having the diversity, at least we could see. Oh, actually, we all speak English only. And we are all upper middle class and we're doing this research with this group of people in New Orleans. How are we going to get a perspective? How are we going to be able to understand their perspective better when we are so different to them? It just brings that identity to the surface so that you don't ...

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Because what sometimes happens in design is that, we assume that the decisions that we're taking represent a mainstream, or we don't understand how our assumptions affect the design process. This is to bring our personalities out in a visible way and we can talk about this. It also helps us see where there might be some hidden benefits within the team, or hidden alliances. Once I did this exercise with a very large group of people, about 75 people and as we were analyzing bubble by bubble because we did this now on a mural but on a remote white boarding app. Right? And as we started to analyze bubble by bubble, someone piped in and said, oh, I speak Vietnamese. And look, there are three other people who also speak Vietnamese. And so it also revealed some very interesting things about your group. Yeah.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah, and things that you wouldn't normally know. Otherwise, I think we've all made assumptions about people's background and sometimes it's wrong. Right?

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yeah.

Daniel Stillman:

And that can be both offensive or surprising or delightful, there's a whole range of possibilities.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yes. You're not going to look at me and know that I speak Portuguese. Right?

Daniel Stillman:

Right. Well, if you navigate in Brazil as we've talked and I would hope eventually you made it through that but it's really interesting because I think we have some affinities, if not shared identities because I studied industrial design as did you. And I think there's the promise of universal design was something that I believe I was taught is that, that was certainly the vision of post-World War II. Bauhaus design was like, let's make things that everyone can afford and that everyone will love and everyone can use and everyone will understand using universal language. And I think what I'm hearing you say is that, that is not necessarily possible.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

I definitely say that that is not possible and like you, I believed in that idea of designing for many. And I actually, when I left university in Brazil, which gives me then a completely not a completely, it gives me a very different kind of framing. Right? I was so in love with the idea of mass.

Daniel Stillman:

Like mass appeal?

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

But I was ... Yes, I loved designing for the masses rather than designing for a smaller group. I actually was interested in that mass design surprisingly through a social lens because I always was thinking. Okay, well, how do we mass produce this thing to make it more accessible to people? But definitely, I have learned that diversity is very, very, very important focusing on the needs. Well, this is a human centered process that we really talk much more about today than when I left university focusing on the needs, the very specific needs of individuals that come up with design that then actually serves more people, I think is important.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. And I want to go to that in a second but the first thing I wanted to touch on in this idea of universal design is, I was reading an article where somebody was writing a very, very high level overview of design thinking and it was hilariously general. They were like, well, so as we all know, by definition design thinking is a human centered design process that has five phases and here are the five phases. And everyone who's not, because there's no video for this. Her eyes widened everyone. That should have come with a trigger warning. I apologize, Dr. Noel.

Daniel Stillman:

But one of the things that I really loved about, I watched one of your talks was the ... I suppose, excessive is the wrong way to put it. The abundant model making that you've participated in. There were three or four different and I want to just flash them on the screen. There was like, oh, a woman in a head dress. And like an organic, it looked like a batik print. And I read an article of your students, many, many self-made models and I have always believed that it's important for people to map and understand their own design process and to craft it for themselves. What is important to you about people making their own design process?

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

I'll tell you my own triggering experience. I graduated in 1999. No, actually not '99. I finished university in '97 and then the ceremony, the walk was is in '98, right? I've been a designer for a little while, right?

Daniel Stillman:

Yes.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

And maybe about three years ago, I was in a design thinking space and someone told me, okay, well, here are the steps, you do this and then you do that. And I said, well, actually, I've been doing this for many years. And they're, yeah, but you have to follow these steps. And the thing is, I found that I was horrified that we had reached this space where people really felt that, okay, if you haven't checked off all of these boxes, you're not doing it right. When those of us who studied in the '90s and the '80s and I think, anytime before 2005, let's say, we were encouraged. Maybe we were shown different processes along the way, maybe each professor had a different model but we knew that we were going through a type of process that would get to an outcome at the end without learning those models. Right?

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

And so it's, while I will actually say, so as someone who studied way back then and we'll actually see then the proliferation of templates of how you do design thinking. It's actually, it can be helpful. It gives you a shortcut where you're like, okay, so maybe I'm in this field and maybe I'm in that field but I'm into something called critical pedagogy, which means that ... No, it's not even, which means that. But using this research, people are actively involved in shaping their own knowledge and so that's why I ask people to draw their own process. I pick them, in my PhD research, I did some work with some children where we discussed what designers do and all of that.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Then I asked them who they would identify as designers and then they told me some people. And then we were together for three weeks and each week I had the children, I asked the children to draw the process that they were using to solve the problem and each week they would look back on the process from the week before and they would decide how they would tweak it. Right? We don't have to show people models for design thinking. We could talk about, okay, what are we doing? And then we could let people create models that are relevant and also see how they have to edit the models to suit what they're doing. Another way that I describe it, which I think people enjoy is I describe it as cooking.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah, design thinking as curry.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yes. You know that word, right? Yes.

Daniel Stillman:

I do. It's a beautiful metaphor and I love curry.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Who doesn't like [inaudible 00:14:37]?

Daniel Stillman:

Jokes. This is just a total side issue, but what do white supremacists get to eat?

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Oh boy. What do they get to eat?

Daniel Stillman:

Do they get to enjoy Thai food or do they think that white supremacy extends to culinary activities as well? Can a white supremacists enjoy Thai food? I shouldn't be laughing but I've always thought it's like, I love Thai food. I love Caribbean food. I'm a Universalist, I come from New York city where we eat the whole world on the street so that's just me.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yeah.

Daniel Stillman:

I'm really glad you talked about this because there was a phrase you used about liberatory versus depository. And I thought this was a wonderfully clear way of explaining how I like to teach people, which is pulling it out of them as opposed to inserting it into their brains. And I think people would be surprised to think that design thinking could be fully decolonized and self discovered by a group of what was it? 10-year-olds?

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yeah. And I think maybe the oldest was nine to ... We had an outlier who was 12. But yeah, let's say ... Yeah.

Daniel Stillman:

What about the C-suite? Can the C-suite do what a group of 10 to 12 year olds do?

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

It takes more work per C-suite.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yeah. It definitely takes more work. Children are more open, even when I work with college students, college students sometimes want to know. Okay, so what textbook is this in? And I'm like, the textbook is forthcoming. But children are open to trying things out and that's something that we have to learn to cultivate. One thing that I do like about the design thinking work that people do and in a more commodified way is, I love how much fun they inject into the process. I sit there and I step away. Right? No, but I want to do it in a fun way but for those of us who are going through design education, it's because it's our main career. It might not have that level of fun but it's like when you take design thinking into somebody's boardroom, you make it all fun and whatnot because it's a secondary space and I think that that fun is important.

Daniel Stillman:

I'm just disrupting you for a second because I feel I have a rare opportunity to actually get you to like ... I'm flashing, I caught a couple of screenshots from one of your talks of just some, what I thought is just a revolutionarily, a radically different way of visualizing processes and I loved this one because this is a black woman wearing a traditional head wrap and each fold in her wrap is a different strength, or focus core area of a design process.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yeah. But this one is less of a process. This is actually an imaginary curriculum where each ... It's a series of curricula that I had been designing. And this one I created, well, in June. In May, June, at the height of the pandemic as a response to George Floyd's murder, where I was thinking of who is excluded very often in design and design thinking and what does the curriculum look like from their perspective? What are the things that a black person ... I am a black woman. As a black woman, what am I going to put into a design curriculum for other black people? Right? And this actually started out of ... I did this in June, 2020 but it's a question that I've been asking for quite some time because I came to the States in 2015.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

And so, I had never taught a predominantly white class before. Right? Even when I lived in Brazil, I was never in a predominantly white design space. And for the first time I was in this space in the US. And I once had a small class, like a Saturday class with all black students and I asked, okay, so why aren't you doing these design classes? And then they said but these classes don't have material that we're interested in. And so that's how-

Daniel Stillman:

It's not for us.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yeah, it's not for us. And so, I've been starting to ask all of these different questions. What do different types of design curriculum look like? Designed by the people or with the people.

Daniel Stillman:

These visuals and this one, which is very organic and sort of cell-like, that was very beautiful and this other one here, very sort of traditional colors. And this one, I love too because it's like, oh, this looks pretty conventional. It's some concentric circles and there's something in the center. What does having a visual do? How does it change the conversation about what we're doing here together, like what our process is?

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

I think if we're talking about how we think as designers and not designed thinking, or how do we think as, we can make it about the two groups, artists and designers. We manipulate information and knowledge in different ways. And so the experiment about drawing new frameworks, drawing the curriculum as an image, drawing processes by hand, these are to really dig into the way that we learn to work with information as people in these visual fields. Right?

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

And currently, my students are not generally not coming from an art and design background and so I have to really bring them back to that space of, it's okay to draw. It's okay to doodle so I have one, at least one assignment within my courses where students have to give a reflection but I ask them to challenge themselves to do the reflection visually. They don't have to but I give them three alternative options of doing the reflection because the assumption is that they have to write. I said, you can do a voice note for this reflection. And then the other thing that they can do is, they can draw because I'm thinking of different senses.

Daniel Stillman:

And different ways of knowing.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Again, different ways of knowing. I really try to do a lot of the work that I do through a conscious lens of anti-hegemony.

Daniel Stillman:

Yes.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

And so in doing that, I'm trying to say, well, okay, not everybody wants to write, so what is the alternative road?

Daniel Stillman:

Can we unpack anti-hegemony for those people who don't know how to-

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Right. Okay. Actually, maybe I'll just use a completely different way of describing it. In the work that I'm doing, I'm assuming that's somebody's perspective is normally considered dominant, or will take up the most space and I'm seeing, how can we consciously make sure that the people who are in the dominant space recognize that they don't, they're not all ... Well, see that they are normally in the dominant space and understand how they have to change that position and also make everything. I'm trying to create these spaces where people with different identities and positionalities can contribute in different ways. And we don't just be food to this person's perspective that is normally dominant.

Daniel Stillman:

It's interesting and I want to unpack this. There's several things I want to make sure we hit on here because in decolonizing design thinking, I don't think many people realize that there are inherent challenges with designing for other people. It's not just that like, oh, and I'll admit my positionality when I've read some of these articles that say like, oh, how can a white person empathize and design for someone else? It's hard to look at the limits of one's positionality, right? And say, because I was certainly taught, I should be able to, as a human being empathize with and take on the perspective of anyone like universal humanity if it's a reasonable position. And yet there are plenty of examples of white Western, "First world people gazing across at third world communities and saying, "I know exactly what they need making it and it not working for a whole host of reasons." Most with which go into them, not possibly understanding the complexity of the challenge that-

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Of the problem. Yes.

Daniel Stillman:

... they're trying to solve. And so this is the question of, how do we ... This is the gaze of the "privileged to the non privileged." And one thing I heard you speak about in some of your talks is seeing power and trying to shift power so inverting it, sharing it, redistributing it. And certainly, maybe you can talk a little bit about sort of the Trinidad for California project because I think that was just a wonderful thumb in the nose of this common pathway of power and inverting it.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yeah. Yeah, so that was an experiment that came about my friend, Glenn Fajardo, who is a design educator in California.

Daniel Stillman:

I know Glenn.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

You know Glenn? Okay.

Daniel Stillman:

Well, that's right. Oh, this is a small world. Well, okay. This wonderful. I'm going to have him on this show for sure.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

The worlds gets smaller and smaller, right?

Daniel Stillman:

Glenn's a deal, man.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yes. And Glenn and I were actually, I think literally we were standing up next to each other. We didn't know each other that well yet and we were probably like, sure, that's a shoulder. We were listening to a conversation and there was something in the conversation that just sent up this light bulb for both of us, that we felt demonstrated the need to consciously decolonize this kind of international collaboration. And we both turned to each other and said, well, okay, how about we start thinking about doing something, right? And so Glenn and I planned this class with a colleague of mine, Michael Lee Poy, who's now a professor at OCAD in Toronto. But Michael is Trinidadian. Well, Trinidadian, Canadian. Right? And so, the three of us, we started this conversation as, okay, well, how do we flip this?

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

How do we have this class so that the students or the designers from the so-called developed country, we want to assume that they are the ones with the power, right? And how do we design it so that the students in the developing country, again, so-called developing country know that they actually do have more power than they think they have? Because sometimes in the international collaboration, it isn't just always about the people from the global North, assuming that they're the ones with the power. It's that in the global South, you also get messages that you are the one without power. Right? And so we wanted to flip that and so we created this class where the students at a business school in Trinidad actually had a little bit more power in the class than the student in the school in California. And so we didn't go through the entire design process but it is a project that I would love to do at some stage where we go through the entire design process. The students in Trinidad had to diagnose the problem.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. And reading the responses of the California students was like this ... It was hilarious. Honestly, I think this was like the best design thinking joke ever because they're like, I don't know.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Oh, is that a joke?

Daniel Stillman:

But they had this experience of like, oh, they just swooped in and I felt like they didn't really understand everything about me. And it's like, well, all right. This is empathy. This is the dawn of empathy in them.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yeah. Yes, and really it's a very reflective exercise. I could see why people might see it as-

Daniel Stillman:

I don't mean to ... It's a cosmic, sorry. My father saw everything as a joke. It's like a cosmic reversal, which is how God laughs at the world. That's-

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

I guess so. Yes. Yes. But where we were trying to get to was some light bulb moments and we definitely got that.

Daniel Stillman:

You absolutely did. Here is the question because a lot of the people listening to this are in corporate settings where there is real imbalances of economic power. The idea that the person inside of a corporation gazes out of the world at a consumer, diagnoses a need, designs for it, that's an imbalance of power. And co-design can seem like paternalism, right? I'm going to bring you into my co-design circle but there's no actual re-distribution of power which is a terrifying thing because that can sound like, I don't know, socialism which United States, Americans have been taught to be afraid off. How can-

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yeah. That's a long conversation.

Daniel Stillman:

It is. How should people who are listening to this who are in capitalist endeavors, who are designing for audiences, change the gaze and transform this researcher subject conversation, redesign that conversation so that it is more egalitarian and that power balance is shifted in a way that matters?

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

You're asking me such a hard question. You're going to edit some of this out?

Daniel Stillman:

We can. Let's talk it out because it is a hard question. That's why I'm asking because-

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

It is hard question. Yes. And sometimes I have to say both to myself and to other people, I am in Academia, which ends up being a luxurious space where I can experiment with ... Actually, in Academia, I should not be maintaining the status quo because I'm in a space where I can be experimental. And then the people who are out in industry can say, oh, they tried that experiment and now let's take that experiment freely in a different way. Right? I was in a conversation with someone, this conversation is tied to your question. I was in a conversation with someone yesterday where I described that class, the Trinidad, California collaboration.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

And I said, well, okay, what does that actually tell me if I'm back into the corporate world? What did students in Trinidad, or actually even before that. Glenn, Michael and I were talking about, where is the power? What's the power that the students in Trinidad have, where is their advantage? Okay? And what is the advantage if you are from ... This will probably sound like stereotyping but I'm going to run that risk, right?

Daniel Stillman:

It's totally fine.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

If you are from Trinidad, Brazil, Mexico, there are some places in the world where one of the advantage of people have, people really know how to socialize and how to build community and how to build networks and all that. And so that was actually how the students in Trinidad diagnosed the problem in California. They said there is a problem here that these people don't understand how to socialize. They are socially isolated and all of the conversations that they had, they picked that up. Right? And so now if I come back to the corporate space, I might say, actually, if I want to design a social network, I need to go to Trinidad, not to California where Facebook is. Right? Facebook should be designed in Trinidad or in Brazil or Mexico, or where people are really good at building community not in a place where people are socially isolated. That doesn't actually answer your question at all.

Daniel Stillman:

Because that's still taking inspiration from another culture rather than-

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Well, engage that. You see, I'm not anti-core design, you know?

Daniel Stillman:

Yes.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

I would still come back to something like co-design or I'm still trying to think how to really answer your question. Yeah. Ask me another one. Push me a little further.

Daniel Stillman:

Well, so what I'll say is the framework that I've seen is called the IAP two framework, which is from ... it's called the International Institute of Public Participation. And they have ... It comes from political participation, this idea of like, I'm going to tell you what's going to happen versus we're going to truly work on this together.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Build it together. Yes.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah, so it's like, am I empowering you, or am I might consulting you, or am I just like informing you and everything in between. This is just me personally. I think, being explicit about the power dynamics is the first step, is like saying, hey, we're just going to listen and we're not going to do everything you tell us, just so you know. I think from my own experience in design thinking, it can be very frustrating to ask people to participate in a process when nothing is done with their input.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yeah. And actually that is my frustration with design thinking. And in some of the work that I do because I have been involved in a few civic type of projects. I really enjoy conversations about utopia and co-designing utopia and co-designing utopian concepts that could lead to policies and services and whatnot. But there is some frustration sometimes as a participant, as you rightly identified, if you get involved in this process, how do we move it forward? As an academic, that is a little bit of my frustration as well. Our students design these fantastic policies and programs that every semester and how do we actually move these forward. But I'm happier with co-designing than nothing at all. Right? I think better co-design could happen if we really have commitment to implementation and I think that that sometimes is not there.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. Maybe this goes to some of the questions we were talking about earlier, before we started about ways of connecting with people and communities in ways that are not predatory, that are synergistic when there's the gaze relationship of like, oh, I'm going to go and study them and then make my own interpretation versus I'm going to actually participate with this community and understand that what they need.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yes. Yeah. I think that that's a possible challenge that we have all the time in research, when you operate through a critical lens, you end up with frustration, right?

Daniel Stillman:

Why is that when you operate through a critical lens, you wind up with frustration? Can I just unpack? That's as a really interesting idea.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

A frustration, because you're reflective.

Daniel Stillman:

Yes.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

And then this even as the designer thing where you know that your design is always in progress so like I've been involved in research where when I sit back and I reflect, I'm like, this could really be much more effective if we did X, or and sort of my frustration question sometimes is, okay, how do we ensure that there is more benefits to the community participants in the project, right? And so, I consider this a little bit of a saving grace for me that if I live with that frustration, I will design projects where there is more benefits. Or if we have that frustration, we will have the eye to see that we have to go through that. And so, I think that little discontent is something that we're going to live with to make things better.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. It's interesting, I think. Certainly, in corporate America, there's always this like, well, let's just get on with it. There's this pace speed of, let's get going and slowing down and saying, well, who are we? And what are our positionalities? Seem like, come on teacher, time's running, we got to get going but having the conversation can give you so much benefit. Can you talk a little bit about the designers critical alphabet? Because I feel like, having that critical conversation is something you want more people to be having more often so you want to spread more frustration at the same time.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Exactly what I thought. Yes. Yes. Before I started, as I had said, so when I was working on that project with the children, one of the board members who was responsible for this school said, okay, you want to get these children angry? And I'm like, geez. I want to make angry, which I actually think that people mustn't be afraid of anger and angry people. Again, actually, I had a conversation yesterday where I was saying organizations actually need one or two angry people who are always going to be pushing you to make things better so you need to figure out, okay, where is this angry voice going to come from, right? Whether it's within the organization, or whether it's somebody from outside and that angry voice is going to push us a little bit, that little bit of dissatisfaction is going to push us to do things in different ways. Right?

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

The thing about the designer's critical alphabet is that, it's me trying to get, I was building tools so even the positionality wheel is one of those. I was trying to build a series of tools to get designers to see the world around them through more complex lenses. Okay? I operate through an emancipatory frame, which is about making sure that I'm thinking about shifting power, making sure there are participants very involved in the work, or that I'm doing the work from the participant's perspective and not from my own so that card that's in there, there's a feminist card. And there are some cards that are around things like attitudes that we have to take on like self-awareness which you might not always have as a designer. You might enter the room and we walk in with our fancy clothes and fancy glasses and all that and we're not really self-aware, right?

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Or you drive into your community project with a big car and we don't always stop to reflect on these things, how we show up in spaces. The positionality wheel is one of those things, that's what we were talking about earlier. And then the critical alphabet is about introducing a new type of language to designers, a lot of languages I picked up in my PhD and in my reading and then with the question below that makes this theory relevant because that's the other thing. If I tell them about decolonizing spaces and decolonizing the field that we're in, we have to make language accessible. Even if we jump away back to design thinking, that's a bit of an issue in design thinking. It's just still jargony so like how do we talk about brainstorming without using that word or prototyping without using those words? How do we make all of this stuff accessible? The critical alphabet is about making critical language, or perspectives accessible. I was thinking specifically about designers but a lot of other non-designers use the tool as well.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. And it's available but people get can get a deck of these cards to thumb through.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yes, they can. They could actually Google critical alphabet or designers critical alphabet and an Etsy link will come up. Or it's tagged in all of my profiles, if they find me on Twitter or Instagram or something like that, they can get it. They'll find the link.

Daniel Stillman:

I think it's one of these things where, I think we share a mission, which is having everyone be a reflective practitioner. Right?

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yes, that's exactly it.

Daniel Stillman:

You did this with the fourth graders-

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yes.

Daniel Stillman:

... to be reflective about their practice, what process do you think you're following? What happened last week? What would you like to happen this week? And don't keep looking back so that you can keep looking forward.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yes. And I teach in a vague way around questions that must be very frustrating for students but at the end of it, it's about them learning to be reflective, to also ask questions and not just assume that the knowledge that is given to them is valid knowledge, so try to question it.

Daniel Stillman:

This seems like the path towards de-colonizing design thinking.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

It could be. I've come back with my vagueness, it could be.

Daniel Stillman:

It could be.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

It could be one path.

Daniel Stillman:

It could be one of many because there's no privileged universal perspective on it.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Exactly. And this is one tool that I've used. Right? And I may design others and I'm also anxious to hear what are other people doing to change up the space? How are other people questioning things and changing things?

Daniel Stillman:

Well, it's very clear. This is the beginning of a really ... I'm so grateful you sat down for this conversation with me. I know we've got a hard stop. People can find you on the internet. I will include all links to that. Is there anything I have not asked you that I should have asked you, parting thoughts on this very broad topic?

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

I'm going to say something really random, it's really hard to grow tomatoes.

Daniel Stillman:

It's January, even in New Orleans, I imagine it's hard.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

You're like, where did this random thing come up? I've spent about six months during the pandemic learning new things. And actually, that's the connection that I'll make, that we just have to go through life with this openness and always this willingness to learn new things and understand new perspectives and talk with new people. The man who cuts my lawn, we normally have a good conversation on all that. We have just been talking and talking and talking about tips about gardening, right? And again, this all sounds random but it's not random. It's about how relationships with people help us to become, I guess, better designers. Now that sounds a little preachy but it's ... yeah, that we have to cultivate this curiosity about other people in life and yeah, could be better at what we do.

Daniel Stillman:

It's really interesting because it feels we didn't talk nearly enough about this, is that design thinking is a conversation between a group of people and relationships. Life moves at the pace of relationships. You can't make a tomato grow any faster than it's going to grow, regardless of how much effort you put into it. All you can do is set the soils as best you can.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yeah. Life is about these conversations that we have and we can design these conversations. And so yeah. How do we design them more intentionally?

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. Yeah. And I think you've given us a lot of tools to think about, power and positionality has the foundation for making sure that it's a clean, a real relationship and not a predatory relationship and not a one-sided relationship.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Yeah, not transactional.

Daniel Stillman:

And not a transactional relationship, a relating relationship, which is really different. Well, this is really great. I'm really grateful for your time. I think there's a lot of food for thought here. Thank you so much, Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel.

Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, PhD:

Thank you. This has been great.