“Stop thinking about drawing as an artistic process. Drawing is a thinking process. If you want to think more clearly about an idea, draw it.”

This is the simple essence of Dan Roam’s message. Dan has written five best-selling books about visual thinking and storytelling. Back of the Napkin was one of my seminal texts, Show and Tell is a blockbuster if you want to learn how to tell better stories...and who doesn’t? And you have to love the title of Dan’s book “Draw to Win”...maybe the most direct distillation of Dan’s perspective. Drawing is thinking...and thinking helps you do better work.

Who should be drawing when many brains are involved in a complex project?

What Dan helped me wrestle with in this conversation is how drawing helps groups think, together and how he, as a model-making expert, can help push the thinking of a group.

We talk through the yin-and-yang of a top-down approach of model making (with someone like Dan pushing the edge of excellence *for* a group he’s working with, vs a group hammering out a new model, bottom-up, doing visual synthesis together.

Both are powerful ways to lead a conversation.

Making a framework for a group can shape their conversation profoundly - the right visual tool can frame a conversation and ease the progress of a team’s thinking: Drawing a classic 2 X 2 creates a frame, a container for a conversation. I’ve always found that, even if someone finds a case that falls outside of the framework offered, they speak about their ideas in relation to the framework - the conversation has been anchored - which is one way to think about what I am calling Conversational Leadership.

There is power and danger in shaping conversations. Leading the conversation can mean that we’ve prevented something else from emerging - something organic, co-created and co-owned by the whole group. This is the IKEA effect...even if something that Dan makes might be technically better than what a group can make on it’s own, they may value what they’ve put their hands on more.

As with all polarities, the middle path, approaching both ends flexibly, is the most powerful. I know from experience how transformative it can be when your client picks up the pen and adds their ideas alongside yours. Who picks up the pen first can shift the direction of the conversation profoundly. Stepping back and offering the pen to the group is a choice we can all take to shift a conversation.

Drawing is how to win in the broadest sense. If you’re the only person drawing in the conversation, you will anchor the conversation and lead the conversation. If you get everyone to draw, the conversation will be a win-win and led by anyone willing to take up the pen.

Links, Notes and Resources

Dan on the Web (learn about his award-winning books and his work and more…)

Dan’s Online Learning space: Napkin Academy

Dan’s favorite, most fundamental drawing:

Some of my favorite visuals from Dan that you can find on the web...

The Power of Visual Sensemaking as an organic process:

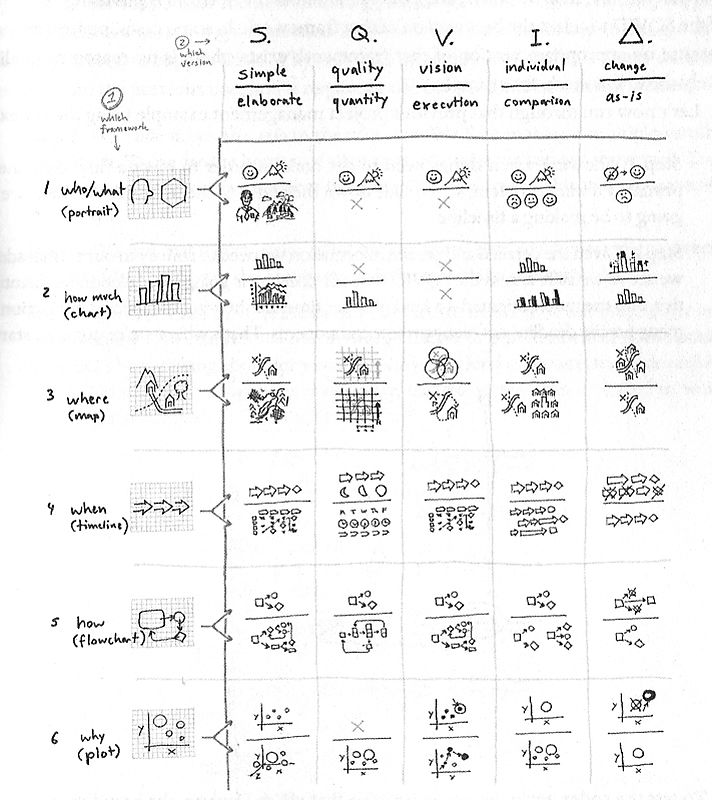

How to think systematically about being visual:

The simple shapes of Stories:

Other books to learn more about visual thinking:

One of my favorite quotes from this interview:

Data doesn’t tell a story

As I always like to say, data doesn't tell a story, people do. And Dan breaks down how to do that, in detail. As he says:

"A good report brings data to life. When we do a report right, we deliver more than just facts, we deliver them in a way that gives insight. It makes data memorable and makes our audience care."

More About Dan

Dan Roam is the author of five international bestselling books on business-visualization which have been translated into 31 languages. The Back of the Napkin: Solving Problems with Pictures was named by Fast Company, The London Times, and BusinessWeek as 'Creativity Book of the Year.' Dan's newest book, Draw to Win, was recently published by Penguin Portfolio, and debuted as the #1 new book on amazon.com in the categories of Business Communications and Sales and Marketing.

Dan has helped leaders at Google, Microsoft, Boeing, Gap, IBM, the US Navy, the United States Senate, and the White House solve complex problems with simple pictures. Dan and his whiteboard have appeared on CNN, MSNBC, ABC, CBS, Fox, and NPR.

Full Transcript

Daniel Stillman:

I'll officially welcome you to The Conversation Factory. Dan Roam, have you always been a Dan? I know this is a strange place to start the conversation but as a Daniel, I'm always curious about Dans.

Dan Roam:

It's funny, you should ask that, Daniel. By the way, a pleasure to talk with you this morning. I'm officially Dan. As far as I remember, I always really have been but when I was very young, when I was in trouble, when something was serious, my parents would refer to me as Daniel. It wasn't a sign that oh, you've done something terrible and you're going to be disciplined. It was just, this is a more serious thing.

Dan Roam:

In my mind, I've always associated the name Daniel with that which is a little more serious than just Dan. I have always been Dan.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. This is exactly what I was hoping we get to because when people call me, Dan, and I'm not a Dan, I take it as a compliment because I think Dan is a fundamentally nicer person. Easygoing guy. Dan, Dan's a great guy. Daniel is a little more serious. I've never been a Danny. I'm assuming you've never?

Dan Roam:

Danny is a no fly zone. We're not going to Danny. When Danny comes out that means someone needs to be spoken to.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah, there's major misalignment. In that case ...

Dan Roam:

Yes, no Dannys, no.

Daniel Stillman:

Okay. I'm glad we're ...

Dan Roam:

This is a no Danny zone.

Daniel Stillman:

This is a no Danny zone. Danny's like he's a good guy, but there's not a lot up top. If there's any Danny's listening, I apologize, but prove me wrong. Come at me.

Dan Roam:

Yeah, yeah.

Daniel Stillman:

Dan, for those of the world who somehow are unaware of who you are and what you're about, what's your origin story? You've written a lot of books. They are all amazing. People should read them but if they haven't, if they're unaware your existence. If we were to just have a quick napkin sketch, if you will, of Dan Roam, what's your origin story? Was there nuclear waste involved? Radioactive spider?

Dan Roam:

There were several nuclear meltdowns involved.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah.

Dan Roam:

Yeah, Daniel, thank you. That's, that's lovely. I am the guy who you all know, many of whom you are, who loved to draw back in school, especially in the early years of school, kindergarten, first grade, second grade. I drew all the time. That's what gave me a lot of pleasure.

Dan Roam:

Then, by about second grade, the teacher said, "Okay, it's enough with the picture books. It's enough with the drawing now that you know how to read let's take the pictures away and get serious, let's really educate ourselves." I was just heartbroken. Because to me, it was the drawing that was the mechanism by which I learned things and understood things and made sense of the world around me.

Dan Roam:

Then, they kind of took it away, but I said no, and I just kept drawing all the way through. My first job out of high school and then out of college was in graphic design. Drawing or sketching is really the core language of graphic design, you just map something out on a piece of paper to try to figure out what it might look like. The fact that I was drawing made sense, but then I moved into management consulting, and I was the only person in the room who still drew because management consultants, by and large, have to had the drawing trained out of them, not only at second grade level, but certainly all the way up through university.

Dan Roam:

It's not something typically that you do. That would be really the essence is I was the business person in management consulting, who did not understand what most of the people were talking about. In order to understand it, I would go to the whiteboard, if there was a whiteboard in the room, or pull out a sheet of paper if there wasn't, and just draw some very simple little stick figures and boxes and arrows. As I was listening to what people were describing and play it back, show it to them and say, if I understand properly what I think you just said, it might be something like this little model that would be on the whiteboard, how does that fit with where you are?

Dan Roam:

Every time I would do that, Daniel, the conversation would totally change. People would say, technically, "Oh, my gosh, I have never seen what we've talked about described that way." The conversation would shift towards ... politics would drop away, the sort of the unspoken who's leading in the meeting would drop away, who's right who's wrong with drop away.

Dan Roam:

What would happen is you'd have a really genuine thoughtful conversation around the picture, the drawing, that was emerging on the board. That's the story. Just never stopped doing that.

Daniel Stillman:

Do you feel like a doodle revolution has happened? I know you had, and we're going to dance all around. You have this amazing platform, The Napkin Academy. I've just started exploring all your draw together videos of two of my heroes, Dave Gray and Sunni Brown and amazing seminal texts as back of the napkin was, for me ... is more drawing happening in the corridors of business? Is it your fault?

Dan Roam:

Yeah. Great question, Daniel. We won. We won. It's been a decade. It's been a decade since my own book back, The Napkin came out, which was probably one of the first business books that was really intentionally and totally about the act of drawing as a way of thinking in a business setting. Many others were right around the same time. Whether it was Dave gray or Sunni Brown, Alexander Osterwalder with Business Model canvas doesn't explicitly talk about drawing but he uses drawing.

Daniel Stillman:

He uses a visual framework to organize thinking.

Dan Roam:

Absolutely. One of the greatest, frankly, over the last decade.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah.

Dan Roam:

There was this moment starting 10 years ago and I think the fact that it paralleled really the rise of social media and our ability technologically to send images to each other, we could always do that through email and things. Now that you think about Instagram or Pinterest or even Facebook, the incredible amount of attention that is given to simple images. There's good and bad on that. This notion of using a picture, whether it's a photograph or a drawing or a sketch to help amplify or clarify an idea has never been new. It's been with us for a long, long time.

Dan Roam:

Many of us just helped push that forward. I think, in a way, we succeeded.

Daniel Stillman:

How does that feel?

Dan Roam:

I don't go into a meeting now where people don't draw and that's not true of 10 years ago.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah.

Dan Roam:

I mean, every time I go into a meeting now, someone's drawing something, which is great. Yeah, I think, it's been successful. Now, knowing that, it's time to push forward on what might be the next evolution of using the visual mind and what have we learned from social media in particular, that maybe isn't quite so beneficial, related to the power of the visual. Because it can be used for good or for not good.

Dan Roam:

I think it's time for us to reflect on a bit what have we learned about the power of the image? How can we use that as we move ahead?

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. I want to loop back because the question I wanted to ask you around top down versus bottom up visual thinking, I think, Alex's diagram was clearly hard one. I think he followed the dictums of ... well here, I'm going to I'm going to pause there, I'm going to loop back around. Do you have a favorite drawing of yours like an iconic like this is Dan's most favorite sketch ...

Dan Roam:

I have two. I have two. Yeah, Daniel, I probably have two. It's a great question, it makes me think how do you pick your favorite after having drawn 50,000 drawings? How do you pick your favorite?

Daniel Stillman:

At least.

Dan Roam:

At least. Whichever one I'm working on right now? No, but there's an answer. The simple one would be the simplest possible smiley face, has become the emoticon. In a way, if you think about it, there are versions of the simple stick figure smiley face all the way back onto the walls of the caves of Lascaux and some of the most ancient written communications by humans that have ever been found are Essentially stick figures.

Dan Roam:

The stick figure smiley face would be my favorite because you can go anywhere with that. There's one more, which is a little more elaborate drawing. It'd be interesting for people listening, if you can, not if you're driving. If you could just close your eyes, just try to visualize with me for a moment, we're going to draw a picture together. What I'd like you to do is just take a sheet of paper and there's going to be three simple shapes on this sheet of paper. Pace yourself accordingly.

Dan Roam:

You're going to draw from left to right. Over on the left, I'd like you to draw or imagine just a square, maybe a couple of inches on the side, just a square, square. Imagine that. Draw it in your mind. Then, to the right of that square, about the same size, draw a triangle, a pyramid, with a point at the top. Then, moving one more space to the right, draw a circle of about the same size.

Dan Roam:

Now, you're going to have three shapes in a line. You're going to have a square, a triangle with the point pointing upwards and then you're going to have a circle. A square, a triangle and a circle, and they're all of about the same height. What I'd like you to do is in between that square in and that triangle, put a little plus sign. It's almost as if we're making a mathematical formula here. Then between the triangle and the circle, put a little equal sign.

Dan Roam:

What we have is a little visual formula that says square plus triangle equals circle. I'd like you to just see that and now let me explain or share with you why I think it's important and what it means. This is probably my favorite go-to drawing of all time to explain and represent the power of a simple, simple picture. The square can be used to represent the world as we know it today. It's square and there's a lot we can go into, Daniel, about really, Carl Jung and the understanding of these sorts of shapes psychologically, what do they seem to mean to the collective mind?

Dan Roam:

A square seems to be a shape that represents something that is known and pretty well understood and stable. That square that we drew represents the world as we know it today. A triangle. Daniel, when a triangle appears in a formula, you just like physics. What does a delta mean? What does a triangle mean? What does it represent?

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah, delta is the Greek symbol for change. Usually, if you put one side a little thicker, that's like, yeah.

Dan Roam:

That's very fancy.

Daniel Stillman:

That's what makes it a delta.

Dan Roam:

We'll talk more about that. The triangle represents change. Now what you've done is you've drawn a picture that says there's the world as I know it, and I'm going to add change to it. When I do that, when I take my square and I add change, do I end up with another square on the other side?

Daniel Stillman:

No.

Dan Roam:

I do. I end up with something else. What might I end up with? Probably something quite different than where I began, a circle. This little drawing, the square, which is known, the triangle representing change, and the circle, which represents what's going to happen on the other side of that change, is a really lovely way to introduce almost any concept of change in a management consulting meeting.

Dan Roam:

Anytime someone's got a problem and you want to try to work with them to help them clarify it, you can start with this picture and say, what do we know about the world as it is? How well defined is your square? Great. You can write a whole bunch of things or draw other pictures and say, my business is perfect. It's highly optimized. Or, I know I'm losing revenue or I'm gaining market share, whatever it is, these are things that are known.

Dan Roam:

Okay, now let's talk for a moment what do we know about change? What's entering into your mind space or into your market space that might be causing you to think about things differently? There's a whole lot you can write there. There's no change in my industry or there's massive change or now that we've got COVID-19, everything's upside down, what have you.

Daniel Stillman:

Yes.

Dan Roam:

Then, on the other side of that, the circle. Say, okay, so now, let's brainstorm a bit. On the other side of that change, what might our world look like? What does that circle represent? You can write or draw. I've gone on for a little longer than I meant there, Daniel. It's simple picture. My favorite. Incredibly rich, no words required, just those three images. What do you think of that?

Daniel Stillman:

I mean, it's interesting because I drew that with you when I was sitting in your workshop at the CIS conference, which was like, again, super fun to draw with you. I'll be honest, at the time, I was like, okay. Now that I'm drawing it with you, I'm like, whoa, because, as I was drawing the circle, and maybe it's because I was just listening to your interview with Dave Gray. I think I learned from him, maybe I learned from you is that the idea of a circle being what's in and what's out, right, that's probably a little washed out.

Daniel Stillman:

The circle is really a fundamental idea of like, what is the whole that we're creating? What's not in that whole? It's just drawing a boundary, just drawing a circle is just ... it's strange how profound it is to say, this is what we're doing. Then, everything else we're not doing. This is and everything else is not.

Dan Roam:

Might we, Daniel, push that a little bit further?

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah.

Dan Roam:

This could be a little philosophical but it's interesting, isn't it that planets are the shape of a circle? They're a sphere with three dimensional circle. Cells in the body tend to be generally circular if left ... anything in zero gravity, that is a liquid or a shape that has the ability to form itself is going to form a circle or a sphere, a three dimensional circle.

Dan Roam:

The circle really is the element of life. It really is. It represents a thing, an organism. By definition, that means there's something inside it and then there's everything that's outside it. It's really this most binary model of all. That's why I intentionally put the circle as where we're going because it's so open. It could be anything, anything.

Daniel Stillman:

The reason I wanted to ask you that is like I have two drawings of yours that I have doodled on here that were very seminal for me. Then, I'll loop back around to the Alex Osterwalder question because the look, see, imagine show diagram that you did in The Back of the Napkin. I don't know if that sparks in your brain, if you can see what I'm seeing of, here's just the world which is all these little shapes and many, many little ... there's disarray.

Daniel Stillman:

Then, seeing is finding order in that, imagining what could be where the white spaces are. Then, making an effort to show somebody what you're seeing. On the flipside of that drawing is the collect, layout, establish fundamental coordinates and visual triage diagram, like those two diagrams I've kept written on my heart for 10 years. The thing is that bottom up sense-making is really hard. It takes groups of people a lot of mental work to establish those fundamental coordinates and to practice visual triage and to make sense.

Daniel Stillman:

Top down is when somebody like you or Alex says, here are these four buckets, let's fill those four buckets. You help somebody's thinking. I think there's this fundamental tension I have as a consultant with people of getting them to create their own thing that they own and they really believe in. Because when they establish their own fundamental coordinates, they are bought in and they get it and it is theirs. Versus here's these four elements, let's get started.

Daniel Stillman:

I hold them in tension because Alex's Business Model canvas does not say, let's have a conversation of what you think the fundamental components of a business model are and let's really think about it and let's come up with your own framework for that. Then, let's change them. He's like hear the nine everyone, strap in, we're going for a ride. In Draw to Win, you're like, here are the four buckets, here's a PUMA, let's get going.

Dan Roam:

What a fabulous, fabulous insight. I would add a couple of thoughts to it. It has been my understanding learned that as the author of a book, the expectation is you provide the top down framework. That's what a book is. A book is not a conversation. A book is a lecture or a magic show or a presentation or a vaudeville routine, whatever it is. The book is you as the expert or you as the authors having a point of view and prescriptively telling the rest of us, here is a way to think about the world, that's what it is.

Dan Roam:

If you choose to take the path of writing a book, number one, you're going to need to have a point of view. Number two, you're going to need to have that framework, that top down. I hadn't thought about it in this way. I think your example, Alexander Osterwalder could have written a completely different book about how to build a business model canvas but he did not write. He said, "Myself and my friend, Yves, Yves Pigneur, have spent the last decade researching how businesses operate, business models, and we have come up with the co-authorship of many, many people around the world, this framework, it works, trust us, use it." He's turned out to be geniusly right.

Daniel Stillman:

Yes.

Dan Roam:

I want to talk just for a moment about frameworks, because that ... you were mentioning coordinate systems, coordinate systems frameworks to me. What I did not share with you when you were asking about my origin story is I have always built models and frameworks. As a kid, I built model airplanes. That was a way to interact with the world and make sense of it. That all I do to this day is really the same thing, building models of what we hear people talk about our systems within a business or an organization.

Dan Roam:

We're building a framework or a model. Often, I make them and I have some skill in doing that. You're right, because a truly interesting conversation workshop or problem solving session is where we do say let's create the framework together.

Daniel Stillman:

I mean, I think, there's something magical in giving somebody those fundamental coordinates. Because when you draw, the four story arcs in Draw to Win, really, you're not telling somebody about how to do every piece of their presentation, but you're saying here are these four fundamental ways that you can draw the arc of a conversation, right? That's helpful for people.

Dan Roam:

It is. I had feedback. I'm constantly, as you are, constantly revising the tools and doing presentations and collecting feedback. It's always an evolving process. I've recently, Daniel, started working with another client, a giant technology company here in the Bay Area, and introduced this idea of visual thinking as a problem solving tool with a 30-minute Zoom session that was very, very well attended and very, very well received and feedback was great.

Dan Roam:

Then a week later, additional feedback as people have reflected even more saying, "Hey, Dan, could you please have been more prescriptive?" "Could you have please just told us what picture to draw when?"

Daniel Stillman:

Yes.

Dan Roam:

It's interesting because as all of us are so busy and so engaged in whatever it is that we need to do, our life, the problem we need to solve, the thing we need to move forward, it seems often what we're looking for is not necessarily someone to tell us what to do. Certainly, someone to give us another possible way to think about what to do, so we can put it in our toolkit and imagine, of all the things that I've been shown that ways to solve this, what would be a good one right now?

Dan Roam:

A tool, a hammer, doesn't normally present itself to you and say, how would you use me? A hammer says, this is how you use me. There is a specific act in your building of a house that's going to require a hammer. There's another act that's going to require a screwdriver and another act that's going to require a saw. Now, this is getting super philosophical, but that is what ... What I often hear from people who have a task to get done is, Dan, the best thing you could do is tell me which hammer to use and show me how to use it.

Dan Roam:

Again, it goes back to what is your role as an author? I think, Daniel, let me turn the question back around to you.

Daniel Stillman:

Sure.

Dan Roam:

You are a conversation starter and facilitator and guider. When you think about the difference between a top down solutioning mindset or a bottom up solutioning mindset, what is the essence of the question that you're after, do you think? Tell me a little bit about your thinking on the difference between those two? Because there's a framework right there.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah, yeah. Exactly. I mean, I think, I came to design from physics and in industrial design, I discovered that I was much better at the research and the talking to people part. When I was working as a consultant, we had to make meaning, we had to tell a narrative we had to explain to our customers, here's what we're seeing in the market. Here's what we think people are doing.

Daniel Stillman:

To me, it feels more honest to look at the data and to enliven it. I actually have a quote here from your book that I think is, "A good report brings data to life. When we do a report right, we deliver more than just facts, we deliver them in a way that gives insight. It makes data memorable and makes our audience care." That takes work to do to hammer out data into information and insight. It's not data anymore. I think the IKEA effect is that people care about the ... we put the energy in and so we care more about it.

Daniel Stillman:

I've always found getting my clients to pick up the pen is profoundly impactful. I guess the question I have for us is, as consultants and educators because you do some of both, some of it is teaching and evoking and other times it's like it's getting them to pick up the pen. It's like, well, why are they paying you if they're doing the drawing? There is that sense of like it's all coming from them, the best stuff does come from them. That's what I love about the bottom up and to ask as much as possible to be an active listener.

Daniel Stillman:

At the same time, I think their intention, I don't think it's an either or. It's like at some point, it is helpful to be like, yes, and let's ... maybe if we push it in this way, it will help the conversation. I don't know if that's answering you but ...

Dan Roam:

Daniel, this is triggering something in my mind, I want to talk if you don't mind about another framework, because it does create that tension of we work from frameworks ... What I'm loving about where we're going with this and this is new thinking for me right now, is there is one act which is the act of distilling and creating a framework. Then, there's a second distinct act which is filling the framework in. Both are very valid and both have a different role to play.

Dan Roam:

Thinking about that, listening to you, what occurs to me is if you think about what Joseph Campbell did in his life, the uncovering and sort of the clarification of the monomyth, frequently referred to we all know as the hero's journey. It is in many ways, at this point, everybody's familiar with the hero's journey. It's become quite a trope. It's a really good one. It is the framework that appears to be very parallel in many, many of the great myths from all of human history. Not all of the myths, but many of those that have stood the test of time and continue to inform the stories we do now, we tell now.

Dan Roam:

It is a very, very simple framework and it is kind of an immutable framework. There are a series of steps that take place in a hero's journey. The beauty of that is we could either rework the journey, which is an interesting exercise that many people do. Or we could accept the journey, basically as articulated by Campbell and many others, and use it as the framework by which we create our story, which is of course, what everyone from George Lucas to JK Rowling to J.R.R. Tolkien knowing it or not knowing it, did.

Dan Roam:

They all follow exactly, their greatest works all follow exactly the same storyline to the letter, to the character, to the tee. Here's the thought. When you are telling a story, how often or when you are telling the story, Danielle, how often do you fall back upon a known framework of telling a story and just use that as a way to tell a great story versus how often do you fall back on rewriting the structure of the story? That's a question for you.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. Right. That's a great question. It seems like what's the business of the moment, right? When it's about creating fresh insight and building something truly new, which some teams do, it's really important to, I think, start from the bottom and build up. Then, maybe the second phase is where you really want to have that fundamental physics of good storytelling. You don't want to necessarily reinvent storytelling unless you're a storytelling consultant.

Daniel Stillman:

Or you maybe want to iterate within the storytelling framework. Yeah, you just want to get down to the business of let's write a story, not, let's not think about the essence of a story.

Dan Roam:

It's funny because you're triggering me, you had quoted a little bit from the book Show and Tell which I wrote six or seven years ago now. What was really fun about that, the core framework of that book, you mentioned this thing called the PUMA, the presentations underlying messaging architecture, that's the acronym, the PUMA, the underlying architecture of the story you choose to tell. I worked and worked and chipped away. Again, in the creating of a framework, and it's kind of a framework of frameworks said, there are effectively four stories that you can tell.

Dan Roam:

Yeah. Anytime you make a blanket statement like that or you come up with a framework of frameworks, it's only going to come ... it's quite a rule, it's only going to cover 80% of the stuff. There are infinite number of other storylines you could tell but they do tend to be a little bit on the fringe. For the purposes of people who are going to buy and read a business book, they're looking for prescription, generally, they're looking for the hammer.

Dan Roam:

Here they are. You mentioned, we have a report, that's fine. Reports tend to not drive a lot of change in your audience. A report might as well just be a written document that's a pre read or something. There's really no point in presenting a report not much interesting is going to happen. Then, you have an explanation, which is really the telling of a story for the intention of specifically teaching someone how to do something. How to sail a boat? How to tie a knot? How to cook an omelet?

Dan Roam:

The steps are pretty well known. There is a series of steps that you can go through. It's not necessarily emotionally exciting, but most stuff that we just need to learn in order to know it isn't always very emotionally exciting like math, there's a series of steps. Then, the third one would be the pitch. The pitch is kind of interesting because what the pitch is it says, hey, we have a problem. I think I have a solution to it. Let me toss you this ball and see if you can catch it and if that means something to you. Do we agree that that was a great way to do it? The pitch is obviously the sales pitch type thing.

Dan Roam:

Then, the fourth framework is back to this monomyth. I just called it the drama. The drama is the ultimate presentation storyline to evoke someone's emotional response. It is exactly, it is Joseph Campbell's monomyth. If you want to evoke an emotional response, an essentially guaranteed way to do that is to tell a story that says, this is us and everything's pretty good today. Boom, some really terrible thing has just happened and because of that, we have stumbled and fallen.

Dan Roam:

As we are falling, as inevitably happens, we accelerate downward and things get worse and worse and worse. Until finally, we're at this point where everything is so bad, we might as well just die. It's all over. It's finished. At that moment, in that pit of despair, some voice comes back into our mind out of a mentor, perhaps a spiritual guide, perhaps it's an ancient memory, something comes back that says, not today. Today, I'm not going to let this thing kill me.

Dan Roam:

It is that moment, that reflection, that spark from inside or from out that allows us to get a foot underneath ourselves and start to stand up again. As we begin to stand up, we begin to accelerate back in the opposite direction, back towards the surface, back upwards. As we do that, one good thing falls into alignment after the next after the next. Before we know it, we push, zoom, come right back across out of the surface and fly higher than we ever were at the beginning.

Dan Roam:

Even Daniel, I'm done. Even telling that, just like that as generic as it was, I'm giving myself goosebumps.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. I'm re-watching half a dozen Pixar movies because there's always that moment ...

Dan Roam:

All of them. Always. All of them, all of the greats, yes, yes ...

Daniel Stillman:

When all hope is lost one tiny glimmer explodes into ...

Dan Roam:

It's that little spark. That is that ...

Daniel Stillman:

Is that teachable? Do you think? I know this is what you profess as some of what you do is to teach people that, the ability to create drama is obviously an important skill for a leader, a facilitator, anybody who's trying to create change. It is not a trivial skill. Do you think that even if you give somebody the framework, the fundamental coordinates of drama, can they follow the instructions and create drama?

Dan Roam:

Absolutely. I can say that with 100% confidence, Daniel, because that is one of the things in my workshops that I do is working with typically fairly senior people in large organizations, sometimes small organizations. The funnest thing that I've ever done in facilitating or training or working with teams is showing people that drama framework, which I didn't make up, nor did Joseph Campbell.

Daniel Stillman:

It's physics.

Dan Roam:

You're right, it's underlying physics. The physics of narrative when audiences ... it's like revealing the ultimate magic trick. It always works. It always works. It always evokes an emotional response. Yes, to your question, is it teachable? Absolutely. You can break the hero's journey down into a discrete number of steps. You can identify the archetype characters that you probably want to introduce at each one of those steps, the typical turns of the story, and you can reveal them relatively easily. We're all familiar with some of the same really great tales and movies.

Dan Roam:

I have seen business audiences for whom, yeah, this is another facilitation session, I'll check the box, I've done my learning and development, my professional education for the quarter. When you have shown people this drama map and ask them to take a business problem that they have, a business problem, I can't figure out the code to finish my game or we're running out of money or we need to reallocate resources or we need to create a new organizational structure.

Dan Roam:

Tell it to me in the form of a drama. Oh my gosh, people do not want to leave the room. That's all they want to do is tell that story and then allow them to share it. There were tears, people are crying over the story of the installation of a new ERP system. Actually, that makes sense because installing a new ERP system always makes people cry.

Daniel Stillman:

It's a fundamental human drama retold.

Dan Roam:

Yeah.

Daniel Stillman:

It's a timeless tale.

Dan Roam:

I really appreciate your question because I just feel the passion coming up in me. Yes, the hero's journey, the monomyth, the drama is absolutely a teachable skill. It is once taught something people never forget and extraordinarily powerful.

Daniel Stillman:

This is really interesting because I want to reframe this because you as a facilitator and a trainer, I'm looking through these four types, the report, just A to B, the explanation, the pitch and the drama. It seems like at least three of those four might need to be alternated and pulled from your toolbox over the course of one session with a group that you sometimes do need to explain and maybe sometimes even pitch an idea to them and to lay out the drama for them as well. I don't know if that's a question. I just realized that.

Daniel Stillman:

I've been thinking about the components, the elements, the fundamental jobs of a facilitator. I had never thought about explaining this dramatic role is really critical. You can deliver that drama. It's a skill you have. You can explain things clearly and succinctly. I quoted a part of a book that you wrote seven years ago and it came out if you like nothing. It's clear to me. What other fundamental coordinates are there, do you think that you think you're drawing from as Dan Roam the facilitator and an educator and consultant, what are your fundamental coordinates in terms of how you're showing up in the room?

Dan Roam:

Yeah, what a fabulous question. It is an evolution from me. I'm trying really hard to improve this. I see it in your work. I was looking through some of your Medium posts and looking through your website and some of the tools you offer. I see this reflected in there as well. The trick for an author is that as we were talking about what is the purpose of a book, a box of knowledge is you must have a point of view. You must be opinionated. You must provide a framework. That's what the book does.

Dan Roam:

By virtue of doing that, it does become about you. There is not an author on the planet for whom the book is not about them. The fundamental question is as a facilitator, are you positioning yourself as a teacher or as an instigator or as an enabler, they're all legitimate. There's a time for every one of them. What I'm trying to do is really think through perhaps better than I have in the past, it really isn't about me. I'm in the room because I wrote a book or have a reputation for something that someone might find meaningful. That's the reason you're invited.

Dan Roam:

You have to keep that in mind. I have seen facilitators who come in and say, okay, what do you want to do today? Tell me what your problem is. That's fine. That works. To me, that falls a little flat. Wait, we already know why you're here. You're here to elucidate us. That's why we've asked you to come. The needle that needs to be threaded by the thoughtful facilitator is the balance between when is it about me and the message I want to share with you? When does that shift to it really being about you and the value you are going to get from this for yourself?

Dan Roam:

It's not easy and there's no great answer. That is the space that I'm really trying to work now. To balance being a good speaker and an even better listener and to have that be true, is really hard. That's the work for me.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. I feel that. I struggle with this too because expertise is what gets you in the room. Pulling things out of them is what widens it up for me. Tell us exactly how to do it.

Dan Roam:

Then, add into that. I hear you Daniel. I think you're right. I think there's a third stage there. You're invited in because you've got expertise so share it with us. Now pull out of us, says the audience, our work but leave us with us feeling that it's truly ours and something has changed in our life. To shift it from being about the presenter to truly being about, we'll call it the participant, but the attendee.

Daniel Stillman:

Yes.

Dan Roam:

Who's then going to leave that meeting or that workshop and hopefully go do something different that's valuable for them and pass that along. That third step is the trickiest one and yet when you do it right, as the facilitator, I will share one story with you. I do a lot of full day workshops at substantial organizations. I would think they're paying me and sometimes as the facilitator, you think it's kind of like you're being paid by the pound. How much knowledge did you leave on the table today? You're right for that.

Dan Roam:

I'll tell you the thing that was interesting that was the big breakthrough, probably five or six years ago, was the more time you spend silent in the latter half of a workshop, the better the workshop is. In the opening quarter or the opening half, you must provide the content. That's why you're there. Once you've provided it, provide less than you think you need to and intentionally design the second half of the day to be one in which you say almost nothing.

Dan Roam:

If you do that, your ranking as a facilitator is going to go up. It's the weirdest thing. You think, but I didn't even say anything in the last half of the day and now I'm getting fives across the board. Yes. I'm talking a lot, but it's the same idea that the best interview is the one in which you get the interviewer to talk about themselves. It's so funny because we all think that we were listened to really well and that's very valuable.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah.

Dan Roam:

That's what we want. We want to be listened to really well.

Daniel Stillman:

Dan, we're getting close to the end of our time. There's two questions. I don't know if we'll have time for both of them. One is what haven't I asked you that I should have asked you. Also like, how can people find more things Dan Roam, your live sketching, your next book, I want to hang out for that. Did I say that correctly? People can hang out and draw with you while you write your next book?

Dan Roam:

I am. I'm writing a new book. It's called the Pop Up Pitch. In two hours, create the 10 pages that will transform your audience. It's a cookbook. It's another framework. It's a very specific framework. I'm writing it together at this point with about 180 other people that have joined me online and we get together once a month. It's called Draw with Dan season two on thenapkinacademy.com.

Dan Roam:

If anybody's interested in pursuing that, napkinacademy.com, Draw with Dan season two. We're not co-writing the book. I'm writing the book, but along the way, everybody else is writing their book too.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah.

Dan Roam:

It's quite fascinating. I really appreciate that, Daniel. I'm going to have to roll off here too.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah, it's time.

Dan Roam:

I so appreciate your time and letting me share some of my thinking. If we wanted to have one, should we do one closing thought? What have you not asked that would have been great to talk about?

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. For our next conversation.

Dan Roam:

We'll leave it for our next conversation is hey, Dan, what is the 10 page pitch? Yeah.

Daniel Stillman:

Okay.

Dan Roam:

We'll leave that for next time because it is the ultimate framework combining to your earlier point, all four of the different storylines. Combine them into one storyline to rule them all. It is the infallible. If you don't know how to tell your story, tell it like this and it will work.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. Dan, thank you so much. People should definitely check out The Napkin Academy. It's shocking how much great stuff there's there without even having to pay you anything. There's also some great courses. I'm taking your online meeting magic and I'm enjoying it.

Dan Roam:

Good. I'm glad. Thank you.

Daniel Stillman:

Thank you.

Dan Roam:

As we've all locked ourselves at home during this COVID time, it's been a great opportunity for those of us that are ... all of us content creators to take more time to create more really, really, really good stuff because what else have we got to do? It's been, in its own way, a good time. It's a lot challenging but it's given us some good opportunity.

Daniel Stillman:

Yeah. No, I agree with you. Dan, honestly, it's a real privilege. It's a joy. Thank you so much for your time and sharing so much of your hard won visual triage wisdom.

Dan Roam:

Thank you for listening, Daniel. I really appreciate it.