Today I talk with Sarah Gallivan Mitchell, Product Owner of in-car interfaces at Faraday Future, a company focused on the development of intelligent electric vehicles.

Sarah is an Ace product designer and it was a lot of fun to talk with her about her work through the lens of conversation design. We touch on some big questions, like “How can software be sincere?” and “What’s the difference between manipulation and Modulation?” And “Why you shouldn’t listen to all of your users all of the time”

Show Notes

Sarah’s IxD17 Talk:

Talk slides are here:

http://bit.ly/unicornhardwareslides

And content is here:

http://bit.ly/unicornhardwarecontent

Ixd17 link (video to come)

http://bit.ly/ixd17link

Faraday Futures

https://www.ff.com/

Discussing Design

http://www.discussingdesign.com/

https://www.amazon.com/Discussing-Design-Improving-Communication-Collaboration/dp/149190240X

Crossing the Chasm

http://bit.ly/crossingchasms

Death Talk from IxD17

http://interaction17.ixda.org/session/spark-talks/

Agile Introduction

http://bit.ly/agilereadinglist

Active Listening

http://bit.ly/activelisteningscript

Kanban

http://bit.ly/personalkanban101

The Easy Hard Problems:

http://bit.ly/easyhardproblems

Paul Pangaro’s IxD17 Talk

http://bit.ly/conversationinterface

Sarah: In every conversation that you have with another human being, I mean, most human beings, they modulate their responses in way to either fit norms, or to put you at ease, or to just not be weird, essentially. So hopefully, as long as you have sincerity behind the things that you do to try to facilitate the best kind of conversation you can have, I don't think you're really in ethical gray territory. You're just being social.

Daniel: Today, I talk with Sarah Gallivan Mitchel, product owner of In-Car Interfaces at Faraday Future, a company focused on the development of intelligent electric vehicles. Sarah is an ace product designer, and it was a lot of fun to talk with her about her work through the lens of conversation design.

Daniel: We touch on some big questions, like how can software be sincere? And what's the difference between manipulating and modulating? And why you shouldn't listen to all of your users all the time. Enjoy the episode, and make sure to check out the show notes for detailed links to lots of stuff that we talked about.

Daniel: Sarah Mitchel, thank you so much for joining me. I really appreciate it. You are the product owner of In-Car Interfaces at Faraday Future, and you've been working for giants like Belkin and Yahoo. And I was looking at your LinkedIn profile and I don't know how you feel about your LinkedIn recommendations, but there was an amazing one that kind of relates to one of the topics that we were talking about last time. I'm going to actually read two paragraphs of this recommendation, because it's so great.

Sarah: Oh my god!

Daniel: I know! "There are those easy problems that you can solve with easy obvious solutions, and then there are those really tough challenging problems you face in product design, whose approach you need to be very careful with. You know, those problems where, at first glance, there may be a hundred different solutions, but none appear optimal. We've all encountered these situations before working with product at all touch points with the customer or user."

Daniel: "Whenever you face tough challenging problems, you definitely want Sarah to be on your team, because she brings a high level of intelligent thought, reasoning, and breakdown that drives the team towards the right approach. Combined with strong leadership, research, and insight, Sarah can get the team aligned and feel confident on the best approach that has been proven in the field."

Daniel: That is a pretty good recommendation.

Sarah: Yeah, right?

Daniel: That is Eddie Lowe, who apparently thinks the world of you, by the way.

Sarah: He's pretty great too.

Daniel: One of your first slides, and the reason this conversation between you and me got spooled back up, was the talk you gave at IXD 17 about hardware, and unicorns being eaten alive by hardware. And one of your first slides says that, "Trust is built slowly and lost quickly."

Daniel: I think you were talking about the conversation between a user and a product, and the [crosstalk] behind it, but it seems like, also, that you were also talking about the trust that you know how to build within a team to get that group together to be solving a problem and being on the same page.

Sarah: Yeah.

Daniel: So how do we do that, Sarah? Let's understand.

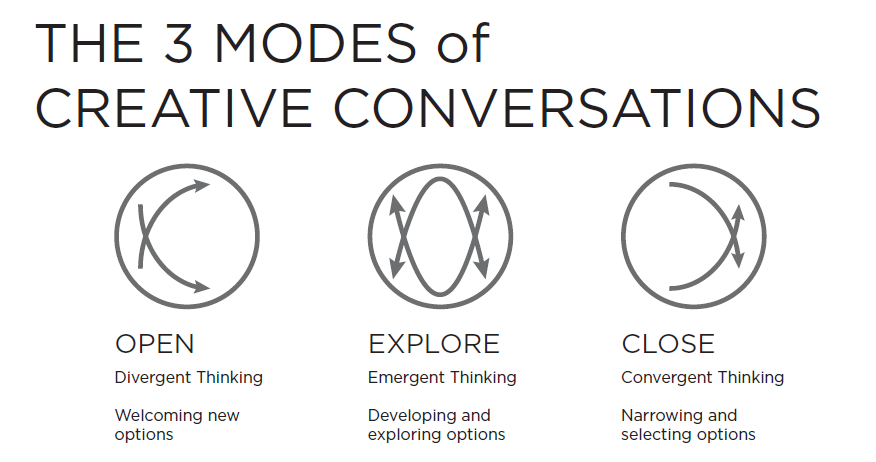

Sarah: Well, first of all, obviously communication is key. You can't build trust if you're not really talking to all the groups. And that's something that I think UX designers are famous for facilitating. But I think in terms of the stuff, the work that we did at Belkin, a lot of it had to do with constantly clearly identifying the goals across all of the groups, and then returning to them over and over.

Sarah: So we did this, we started out by working really closely with the product management team, the product leaders, and engineering and talking about their strategic goals and things they would like to accomplish. And then we looped in user research in terms of how the products were fairing as they were right then. And synthesize that into what we call design principles, just five of them. And then we hung them up everywhere and talked to everyone about them. And the thing with it was not just once, but repeatedly. At the beginning of every design presentation I would do about every step of design work we were about to take, I would talk about them.

Sarah: When we would review something, we would have to bring it up again and say well ... Because lot's of different people want lots of different things, but if you've agreed on a goal, then it's much easier to make a decision if you can refocus on it.

Daniel: Wow, that is so true. So I don't know if you went to any of the workshops at IXD 17, but Aaron Irrizary whose name ... I can never pronounce his last name right, but he and another guy named Adam who works at Mad*Pow, they wrote a book called Discussing Design, and it's a great book about critique. And one of the things they say is if you're going to critique a design, you have to have a better objective than I like it or I don't like it.

Sarah: Right.

Daniel: And having those goals being really ... Having group agreement on them, and then not seeing them once, but seeing them over and over again, that seems obvious. But obviously, everyone doesn't do that.

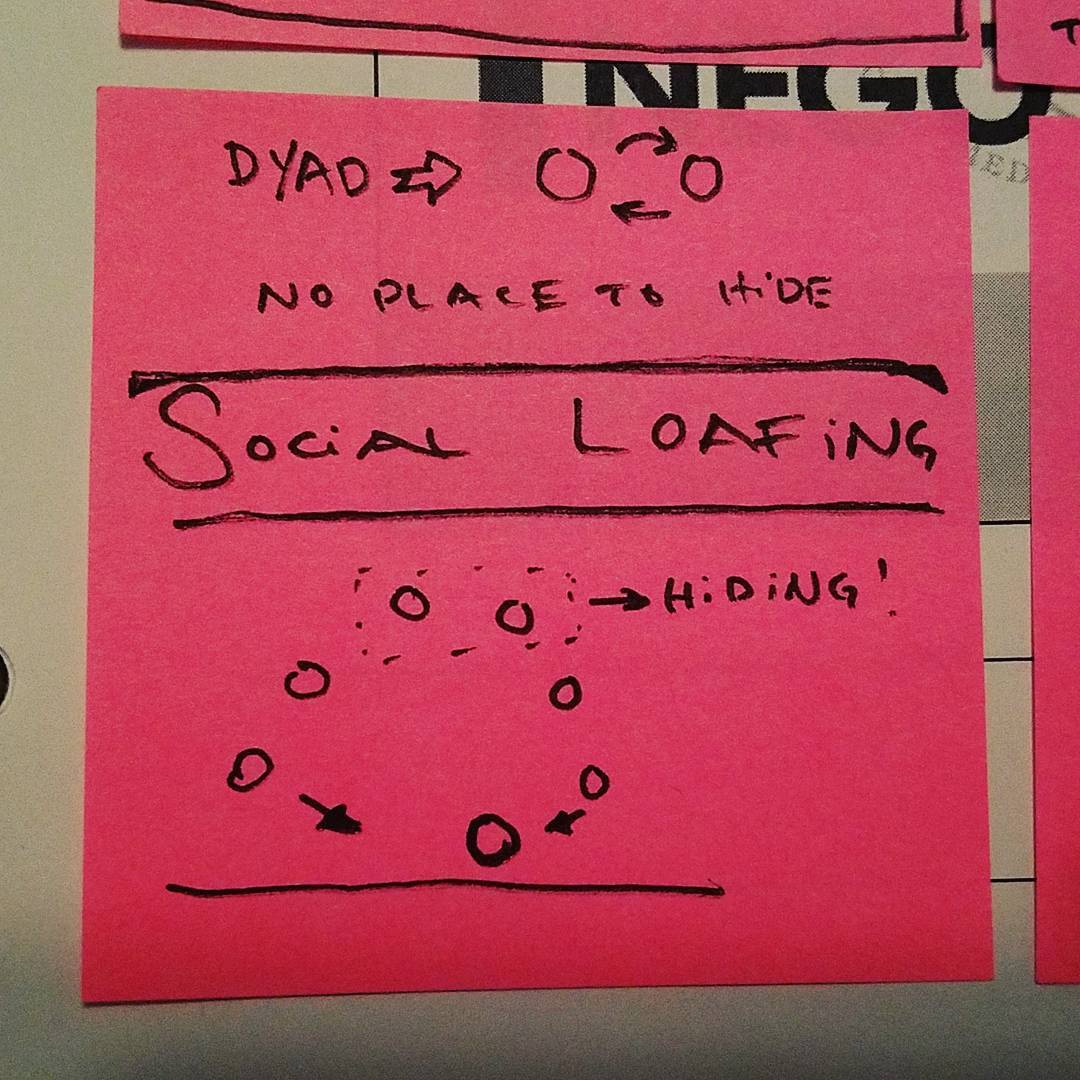

Sarah: Right. Yeah, because there are smaller goals that you need to identify. What is our goal for this piece of thing that we're working on, this design, or this screen, or this piece of functionality? And then there are larger product goals, and those aren't always the same exact thing. I mean, they should definitely align, but ... One of the things I talked about in my talk was that it's easy to get led off a side path by your very vocal early adopters. And this was something that we definitely struggled with at Belkin. I mean, it was a group of people who were totally dedicated to the product, who were really, like I mentioned, rabid review writers, and they were active in our forums.

Sarah: So they had a very loud voice, and we obviously liked them a lot and wanted to support them, but we had to recognize one of the goals that we had was about making the product really accessible to a wide market. Which is not always the same thing.

Sarah: Like advanced features. Extra controls, and fine tuning ability, and complex scheduling, and all this kind of stuff that your very techy early adopters want is not going to take you to the same place that you would go if you're focusing on start simple and work up from there.

Sarah: So we have quite a couple principles that were found around that about bringing in new people and making it easy for them to get started, and then also, one about didn't close any doors on those early adopters. So although we might not have designed the whole product with them, we want to make sure that they have a way to still feel empowered and special. But to give that the right amount of effort.

Daniel: Yeah. So you had goals at Belkin that were clearly defined about making sure that you were balancing those different user needs.

Sarah: Yeah. We tried.

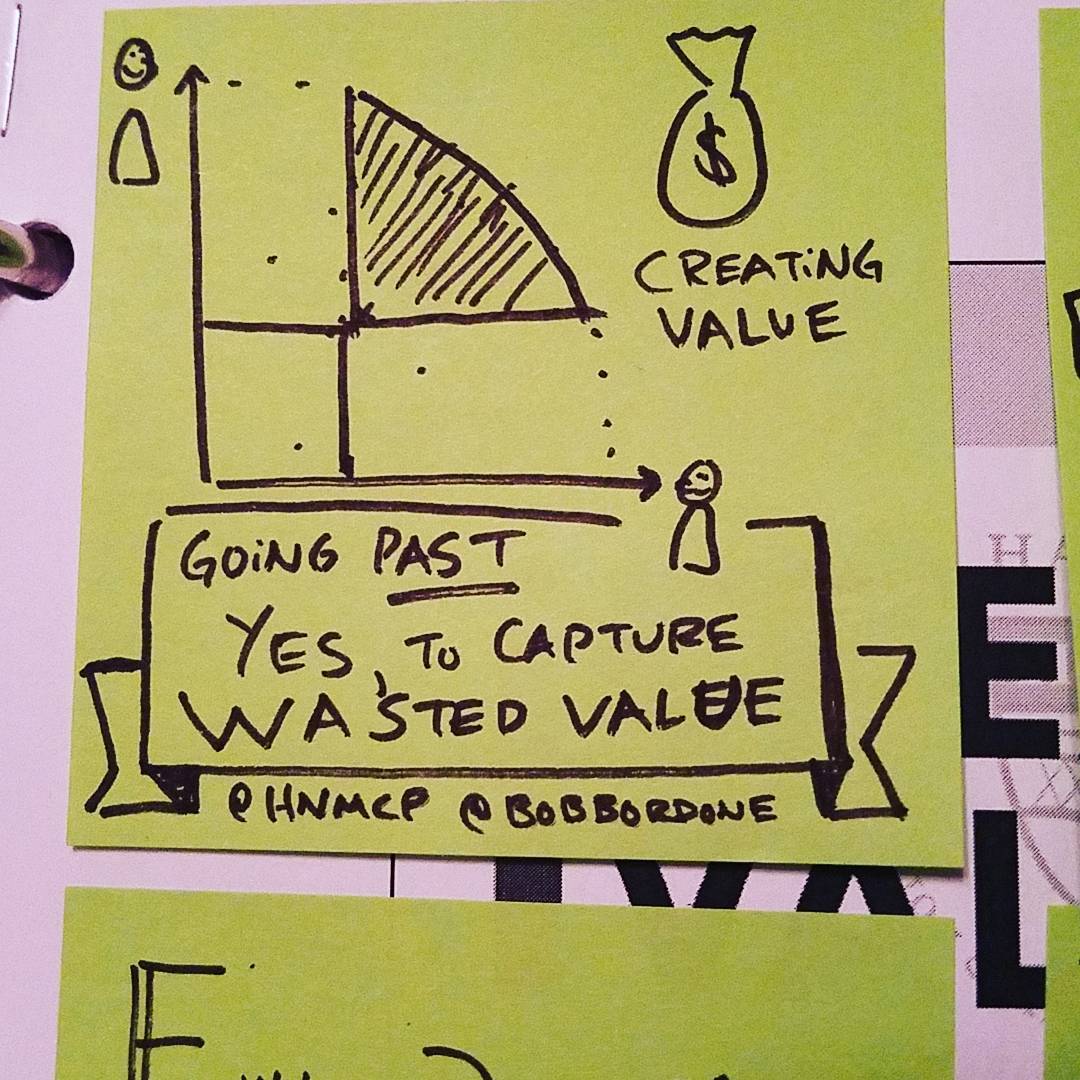

Daniel: So did that make it easy to say yes to things, or did that make it easy to say no to things, or both?

Sarah: Hopefully both. I mean, I was really particularly focused on the no. Definitely both are important, but in any fired up organization, you have more ideas than you can do. So it's really important to know which ones to say no to. I mean, I've never worked at a place where resources and time were not an issue. Everything could get made whenever we thought of it.

Daniel: Ah. Yes. That is a place ... Well, I feel like you're saying you can't have everything, because where would you put it? You'd put it everywhere! And everything is already everywhere.

Sarah: Yeah. Yeah, so it's really important because if you say, "Oh, we just spent six months working on this thing." You want to make sure that that thing is going to actually help you out.

Daniel: Yeah. You know what's interesting about the ... You're putting, the way I would put this in my conversation design language, is you're putting this sort of wave guide on either side of the conversation so that it flows, but it flows within these walls. And it seems like those walls, these goals, are things that you've co-created.

Sarah: Yeah. The co-creation is super important.

Daniel: Right. So the people are willing to stick to the goals because you've made them their goals. They are their goals. It's not an illusion, right?

Sarah: Right.

Daniel: And that's a really important thing. If I'm running a workshop, it's the same thing. I make an agenda and either I say, "Is everyone okay with this? Can we change it?" We talk about the rules of the room and we align on it. But the goals have to be co-created, otherwise it's very hard to get people to-

Sarah: Yeah, I was thinking about this topic a little bit in preparation for this conversation, and I was thinking about another example-

Daniel: You prepared for this? That's wonderful! I love that! I want to make it as easy for you as possible. What did you do to prepare? That's great.

Sarah: Just a little bit of thinking.

Daniel: That's good! Just some light thinking.

Sarah: You know, because especially when you're working on hardware, there's so many different groups that speak so many different languages.

Daniel: Yes.

Sarah: In terms of what they're focused on and what they spend most of their time thinking about. And one of the-

Daniel: Can I just apologize for interrupting you, but I'm from the product design world, but somebody listening to this might not be. So can you outline what are some of those languages, and who those people might be? What is that, who are the people in your neighborhood that you are ...

Sarah: Yeah. So obviously, many of us are familiar with the difference between a designer, and a software engineer, and a product manager, right? Hopefully they all have the same goal, but they're focused on different things. The designer is focused on either aesthetic quality, or usability, or that magic spot in between. And engineers can be just focused on efficiency, and/or simplicity. With engineers, they're either focused on how simple is it to build and maintain, or [crosstalk 00:12:26].

Daniel: They won't break.

Sarah: Make it because it's cool.

Daniel: Yes.

Sarah: So they're really focused on the underneath side of it, and designers are focused on more of the surface layer of it a little bit. And then the product manager's are often focused on the business aspect of it.

Daniel: Right. On time, on budget.

Sarah: Yeah. And then when you have hardware, you also have other disciplines that are in the mix as well. So you have industrial design, which is very focused on the form of the product itself, and the interactions with the hardware. They, plus mechanical engineers, together have to ensure the manufacture ability plus the structural integrity of it. And then if you have electrical engineers who are trying to figure out board, and then also how it meets all of the electrical certification that it will have to pass for safety. And then also the firmware.

Sarah: And when you have this thing that's running your software that is basically kind of its own little server, from the firmware, you also have to worry about all kinds of stuff that you don't have to worry about with a website or with an app. [crosstalk 00:13:37].

Daniel: Right. And it's on wheels, by the way, and it's moving fast and could kill someone.

Sarah: And it's stuck in someone's home ... Well, in the car in that case. Or it's stuck in someone's home. It's in all these different environments. You have to deal with things like dependability. Yeah, that safety and dependability and longevity of a thing that you don't worry about when you're just talking about code that's posted on a cloud server.

Daniel: Which is so easily replaceable. Whereas a steel mold, not so easily replaceable to make plastic parts. And you talked about this in your talk, upgrading firmware, which sounds like, "Oh yeah, we'll just upgrade the firmware." Is not that awesome to do either.

Sarah: Right. And there's no ... Your phone manufacturers try to make it as easy as possible for your apps to get upgraded, and it handles a lot of stuff for you. But when it comes to hardware, a lot of that process itself has to be really explicitly designed by whoever makes the product. When is that firmware upgrade going to happen? Is it going to happen automatically? How do you make sure that's not disruptive? If it's not automatic, how do you get someone's attention? How do you convince them that this is something that they have to do?

Daniel: All right, all right. I feel the paralysis. It seems like that's an environment that is very hard to make decisions in.

Sarah: Yeah. Well, it just adds a lot of conversations that you have to have.

Daniel: Yes.

Sarah: So the example I was thinking of is when you're talking about quality. One of my other points was that quality is king. If you're thinking, "This doesn't work," even just a couple of times, you're just totally done for. It's either ... There's no tolerance for that. So you have to have really explicit conversations with all of those groups about what quality means.

Sarah: Everyone might come with their own assumption. If your device really needs to be rebooted every now and then because there might be ... The Firmware has just the tiniest little gap in it somewhere, whatever. Software needs to be rebooted, we all know.

Daniel: Yes.

Sarah: Is it okay if it has to be rebooted every month? Or what if your engineers feel like it's okay if it's rebooted every week? Is that a realistic expectation? How does that impact quality? Like, "Yeah, sure. All you have to do is switch the power on and off and then it's fine."

Daniel: It degrades. That's the trust being lost quickly, that's one of those things that that can start to degrade somebody's faith in the product. It's great, but Jeez-Loueez, this thing.

Sarah: Yeah.

Daniel: And the engineers are like, "What? Just flick it on and off."

Daniel: But it's such a different perception.

Sarah: Exactly. And so you have to really walk them through what that scenario is like in real life in order for everyone to feel the same thing about what are our quality goals, and what exactly is it that we're shooting for.

Daniel: So you talked a little bit about Belkin and some of the goals, the design principles that you guys agreed on. I've done some research on Faraday Future, and I don't know how much you can talk about your work there now, but could you say a little bit about what is Faraday Future? Where you are in the journey with the company, and anything around some of these goals, and navigating some of these challenges that you're dealing with?

Sarah: Yeah. I mean, Faraday Future, we are another order of magnitude, more complex because it's an automobile. So we are ... And I can't talk too specifically about it, but we are a startup, an automotive start up. And we are very much interested in not doing things the way everybody else has done them before. So it's an electric car, and obviously, many of the car components have to be like a car that you're used to, or it would be very weird. But in terms of the internal digital experience of the car, there's going to be a lot of stuff that's very new.

Sarah: We're still in somewhat early stages with that right now. So we're still at the expectation setting across teams level. I mean, we're doing a bunch. There's so much work to do, there's so many things to design and to make, that we are still trying to ... We're working in detail on some, and at the framework level on others. But we haven't ... The car, we revealed the car at CES this year, so just in January. And we pretty much revealed only the exterior of the vehicle. A lot of work on the interior of the done, we just haven't revealed it yet.

Daniel: And it's a beautiful car. It's very cool. The texture treatment is awesome.

Sarah: Yeah. And the inside is super cool too, and I can't wait to be able to share that and to share details of what the digital experience is going to be like with it. But we're still working somewhat removed. We're thinking a lot about the car context, and we have a lot of ways to test things in the car context, but not fully yet. We don't have enough ... We're not quite at the stage in development yet where we have enough access to the vehicle to be doing real drive testing of our interior systems yet, so we will have a lot of those conversations.

Sarah: And we do have a lot of them with ... We have even more groups, because we have three different levels of servers and processors inside the car.

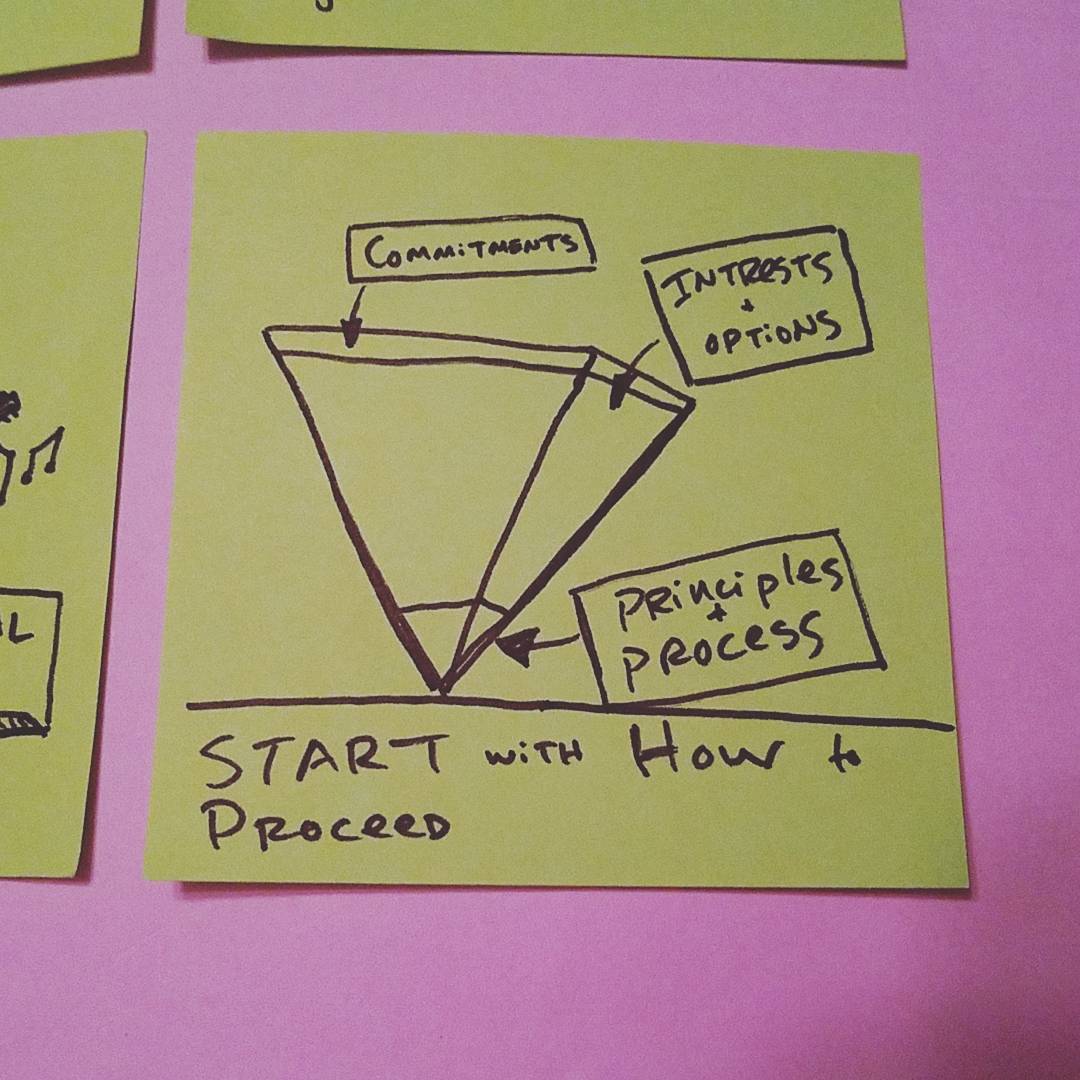

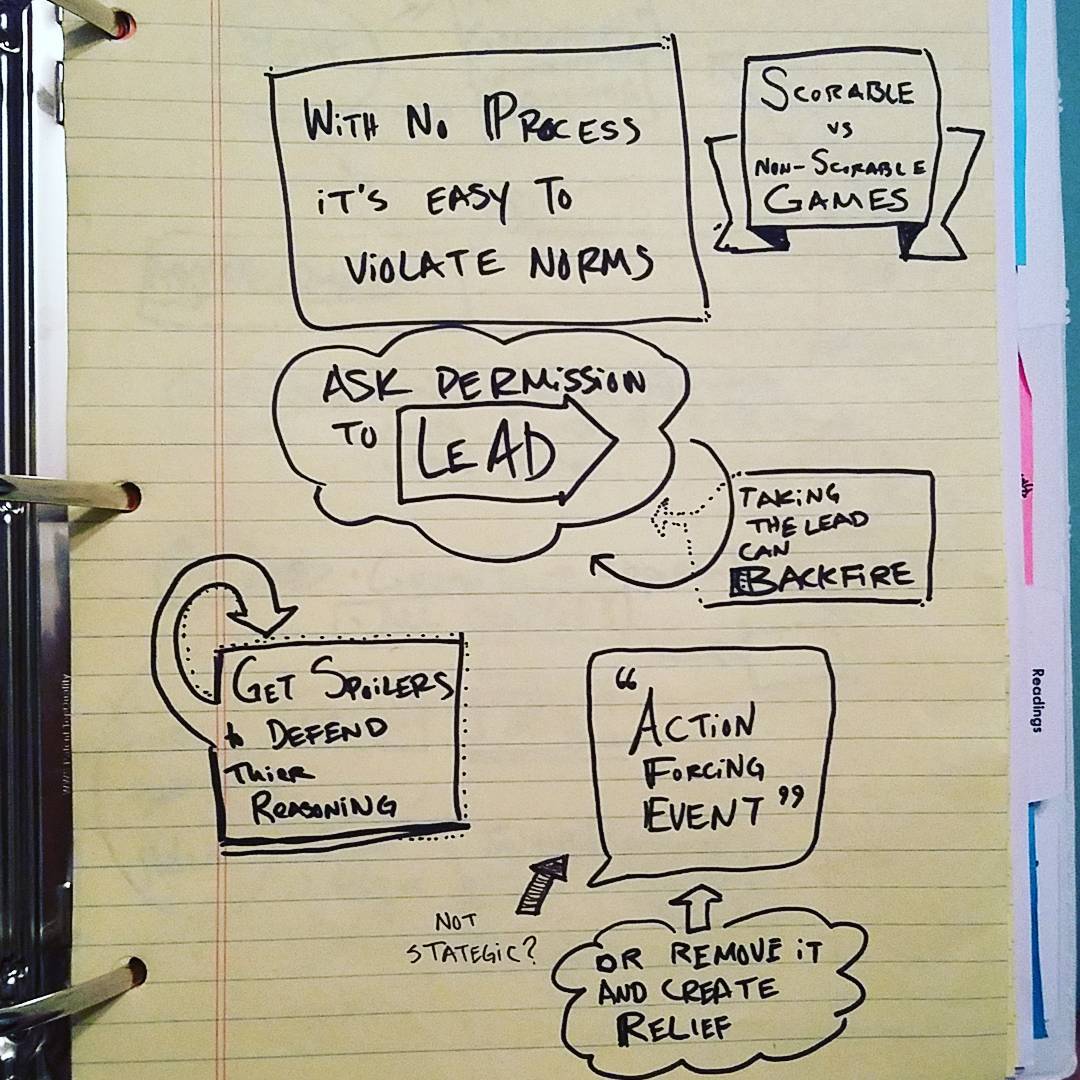

Daniel: You talked about the detail versus the framework level conversation, and that's a really interesting thing that I think everyone probably has to deal with in their work. And that's setting the expectations for the level of detail that a conversation should go into. And to create that barrier, to say, "Today, we're talking about a framework. And if you go into details, it's not going to be so helpful." And, "Today, we're talking about details, and if you try to change the framework, you're a jerk."

Sarah: We've all had that experience though, right? Sometimes, it's inevitable. And I think one of the lessons someone gave me once is that it often goes down to the detail level because that feels like a thing you can control, whereas the big level is a little harder to grasp or to understand.

Daniel: Well, yeah. And also, it seems, one of the challenges, I think, is when you've got multiple stakeholders. You've talked about all of these different concerns. Industrial design with manufacture ability, engineering with reliability, interaction design with usability and the four dimensional experience of an interface. Everyone's got their own details that they're concerned about, and the framework is something that has to connect all of those dots.

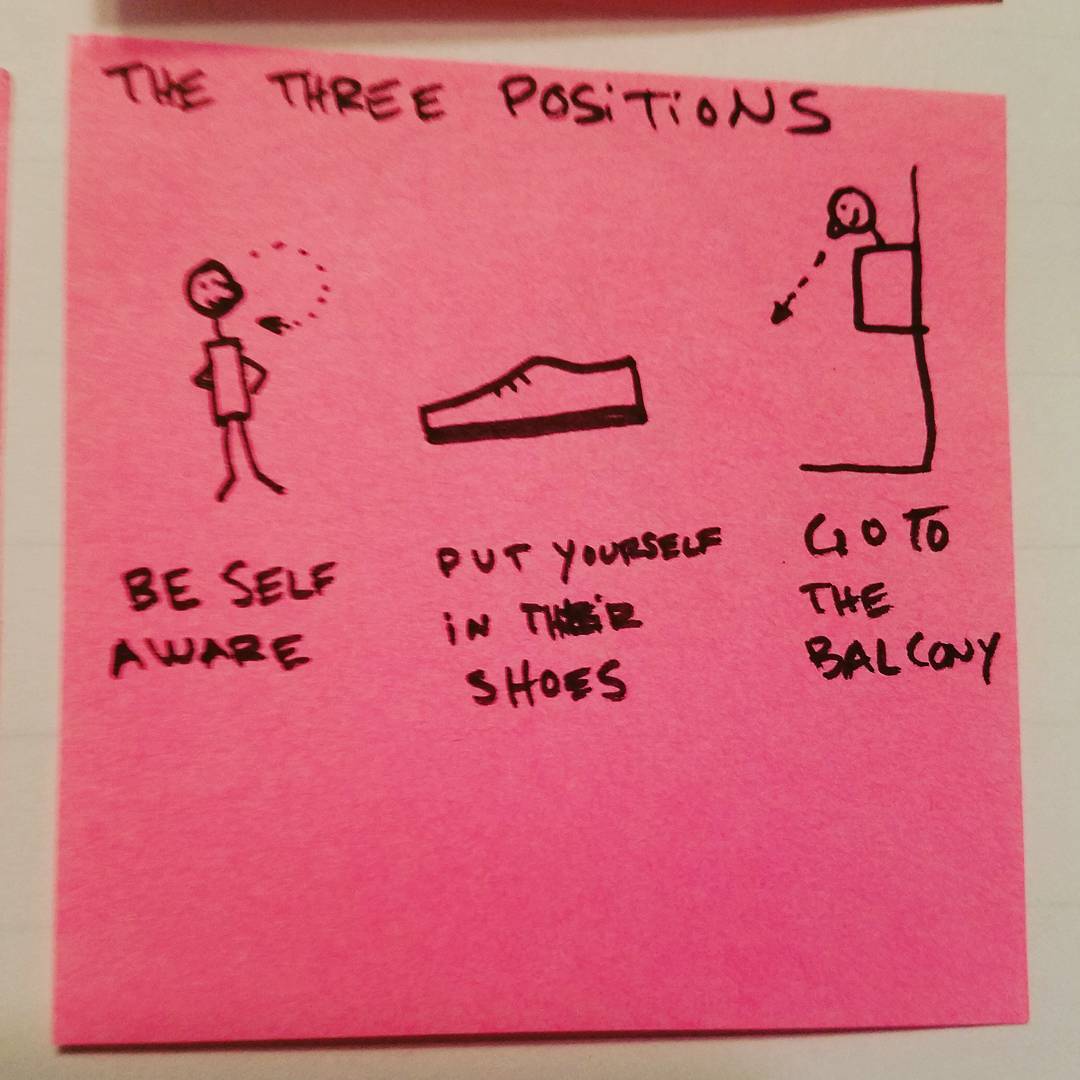

Daniel: So everyone has to, I don't want to say feel like they're giving something up, but has to really deeply empathize with everyone else's concerns. So how do you know? You apparently are good with this strong leadership. How do you ... What advice can you give to people around navigating that interplay between everyone's concerns? And empathy for other people's concerns at the same time.

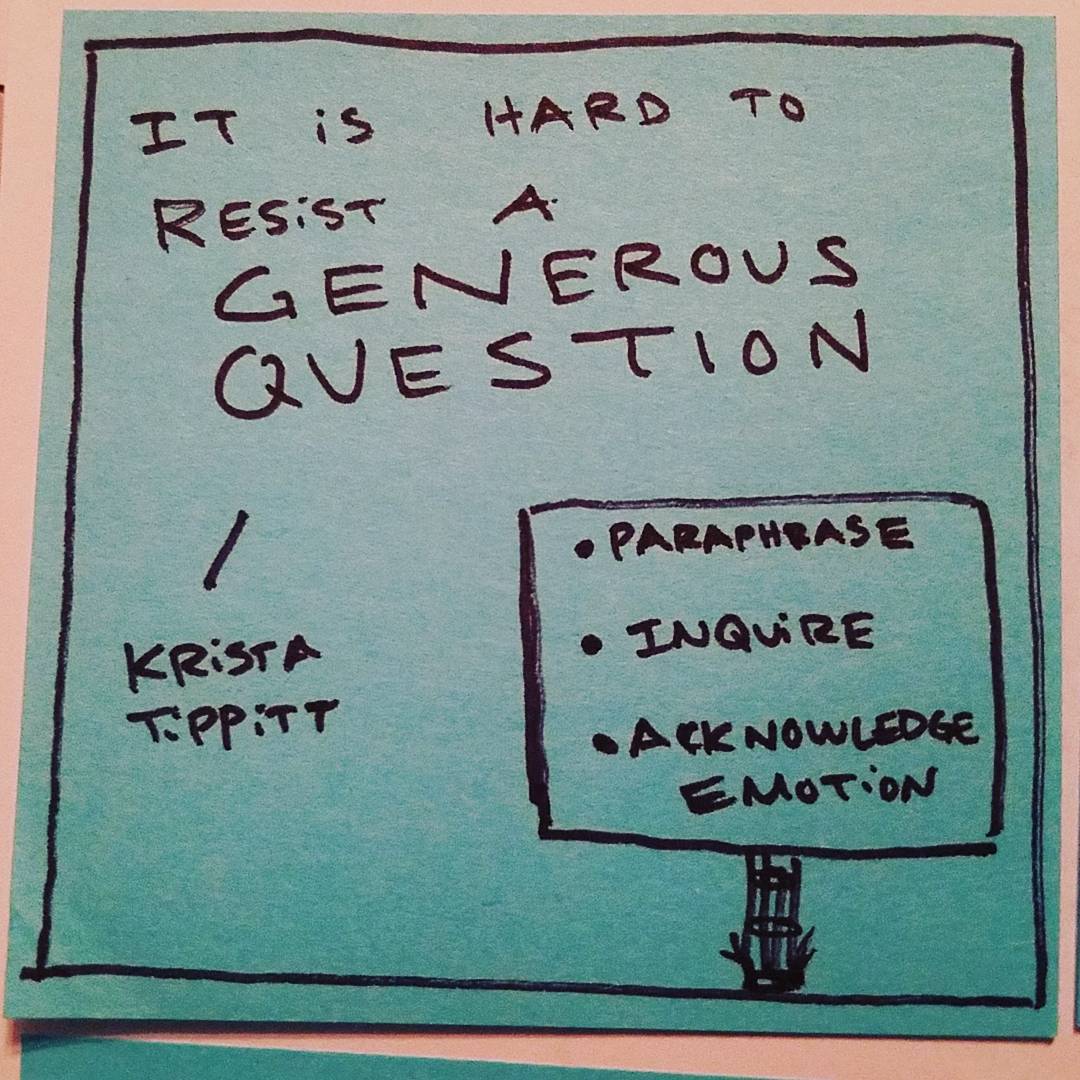

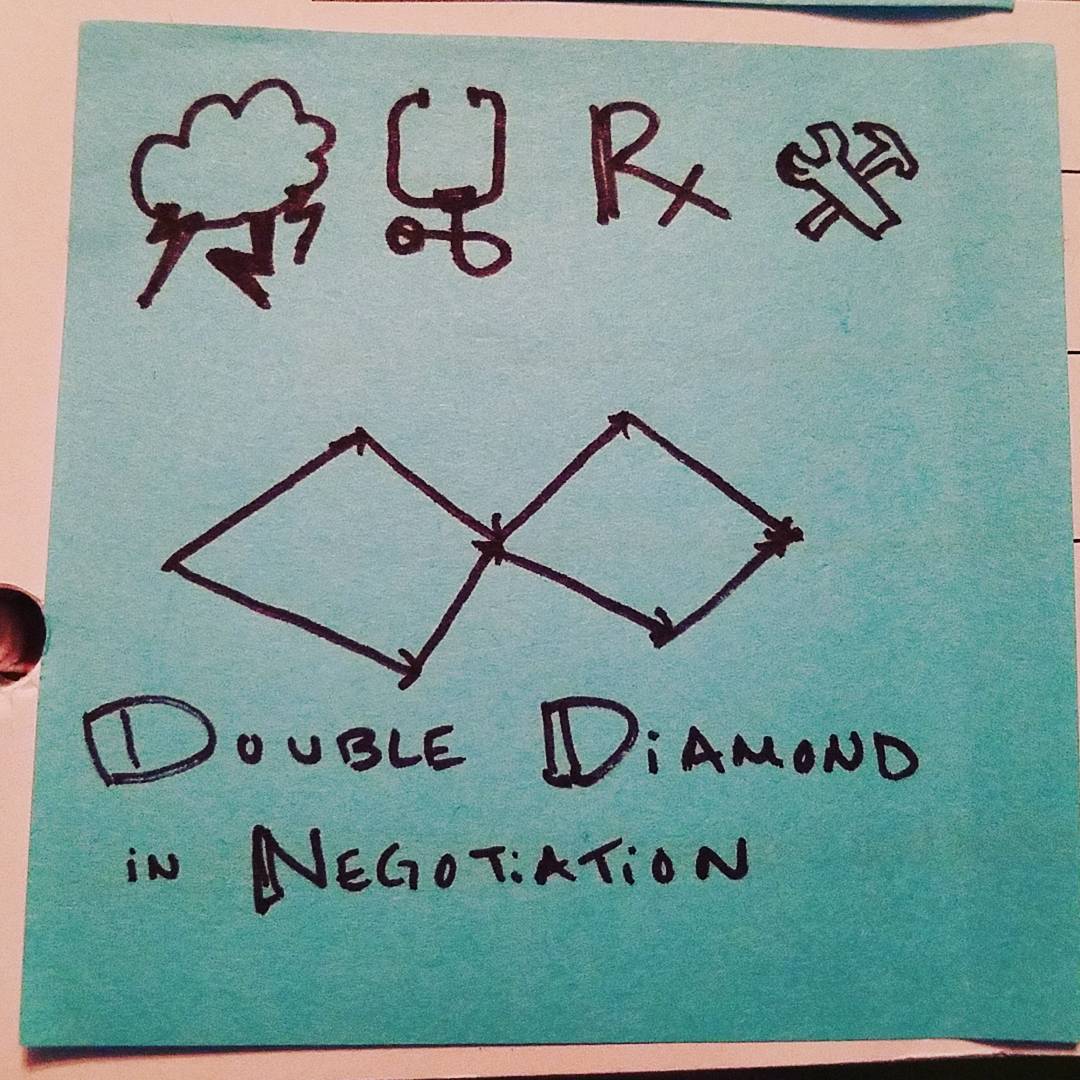

Sarah: So some of that is just good conversation skills, which is that you can really verbalize that empathy. That you can say, "I hear what you're saying and it sounds like this." And repeat it back in clear terms. And what you want from that is this, so I understand why you're saying that, and then you can say, "And now we're going to talk again about the context. This is where we are, this is what these other groups want. This is what the overall goal was stated to be." If we want to readdress what the overall goal is, or if we want to readdress the context, like do we have an additional two months for development, or something like that.

Sarah: Then you can make clear, what are the components you're talking about and not just my way versus your way. But what is the actual outcome of that?

Daniel: Yes. And this is, it's a very ... The way you're describing it is very rational and I think I ... I'm drawing the picture in my mind that I think I've drawn in these situations, where you're like, "This is where we are, this is where we need to be, and these are your concerns and these are their concerns. And if we do everything, then we add five months and have our whatever millions."

Daniel: And then we say, "So now we're all faced with a choice."

Daniel: But to be able to get to that choice, you have to do that very deep listening.

Sarah: Yeah.

Daniel: Right? It sounds like-

Sarah: Yeah, it's super important.

Daniel: Right. And you used the phrase that I use when I teach people interviewing skills, which is just the active listening of like, "So what I'm hearing you say is this."

Daniel: Is that right? You're saying you're here, and you want to get there. And I think that some people sometimes feel that that is a little facile, but it's a really important skill of just literally making sure you heard somebody right and then making sure that they heard themselves.

Sarah: Yeah. I also think, when you do it right, again, not to be controlling, but just when you cal really show someone that you've heard what they're saying, because sometimes they don't know exactly what it is that they want either. They're just having a reaction to something.

Daniel: Yes.

Sarah: But sometimes, when you can clearly identify and succinctly state what it is that they're driving towards, what it is they actually want out of it. Sometimes I get this where I feel like there's a sense of relief on their face. Oh, yeah. Because everybody wants to be heard.

Daniel: Yes.

Sarah: It's super frustrating in a situation when you feel like someone's like, "That's nice, but no."

Daniel: Yes. Well, the classic example of when, and my ex used to say this, "Don't tell me I'm overreacting." You're just reacting. And just listening to somebody's reaction is sometimes the best thing rather than trying to oppose it.

Sarah: Right. I think it's also important actually to have a process for cataloging those things. So you may come up with, "Oh, hey. We all have this goal, and we all agree we want to have this release on this date, so we need to put something in this right now in this release."

Sarah: But what are you going to do with that feedback then, to make it feel like it's not just lost? We're still, to be honest, we're still working on that process at Faraday, but at Belkin, we used to use Agile for design. We used to use JIRA, and we would use it as a way, we'd be able to say, "Hey, that's a great idea. And if you write a story for that and put it in the backlog," then we know it'll be there and we can talk about prioritizing it when we have more time to do something new so that it's not lost. That you have this process for capturing.

Daniel: So JIRA, for people who don't know, is a ticketing system, basically, where you capture user stories and put them against what you want to make, and they become backlog.

Sarah: Yeah. We just used it. we used it basically as journal items, so that everything would stay in a place where it could come up again for discussion.

Daniel: So what you're talking about there is also making work visible, which is one of the things that Agile is really good at. I lately have just gone back to having a Kanban board on my wall for just my own stuff, because it's just the best way to make work visible.

Sarah: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Daniel: You're like, “These are the things I said I would do. These are the things I'm doing, and these are the things that I've done. Don't I feel nice about that?” It's like people forget that done part too. And I think that's what you're also saying with we have to do this release. What can we do that is going to meet our standards, right?

Daniel: You said something though, which is really interesting, where you said that a person will sometimes react to a certain detail, and I think that is ... My suspicion is that there's a moment where somebody experiences some panic or fear, or a feeling of, "I'm not going to get what I need." And it seems like what you're talking about with the active listening was just giving people a chance to be heard, and then also to step away from that a little bit.

Sarah: Yeah. I mean, I think I've experienced it more as frustration, this, "Oh wait, but this isn't what I imagined." If someone had something in their head that they thought as the most important thing about it or some other way to express it. And they don't see it, and then they feel frustrated.

Daniel: Yes.

Sarah: But that's just not part of what they're seeing. And then they articulate it, and then you say, "So I hear what you want is this, and maybe we did miss it, or maybe you didn't have it communicated before. Maybe that wasn't our priority for right now."

Sarah: So as long as you can then say, "We hear that loud and clear and we'll put that somewhere so it won't get lost."

Daniel: Yeah, it gives them that sense of there's some psychological safety that's being given to them. Where there's, "I understand that I'm being heard. And even though I'm not being listened in some sense, this is not actually going into the release, but now I understand that I will be included. I have the opportunity for inclusion in the future," Which is great.

Daniel: So I wanted to shift gears. One of your slides from your talk was a picture, which think is from Crossing the Chasm.

Sarah: Yes.

Daniel: Right? Which is a great mental model that I think everyone needs to know about, and I want to talk about this because I don't think many product designers think about a product as a conversation between a team or a company and the people who use it. And you are talking about managing multiple conversations, where you've got the early adopters who are super enthusiastic about your work and are giving you feedback. Very happy to fill out all the surveys you might send to them, who will maybe even sign up to be beta users.

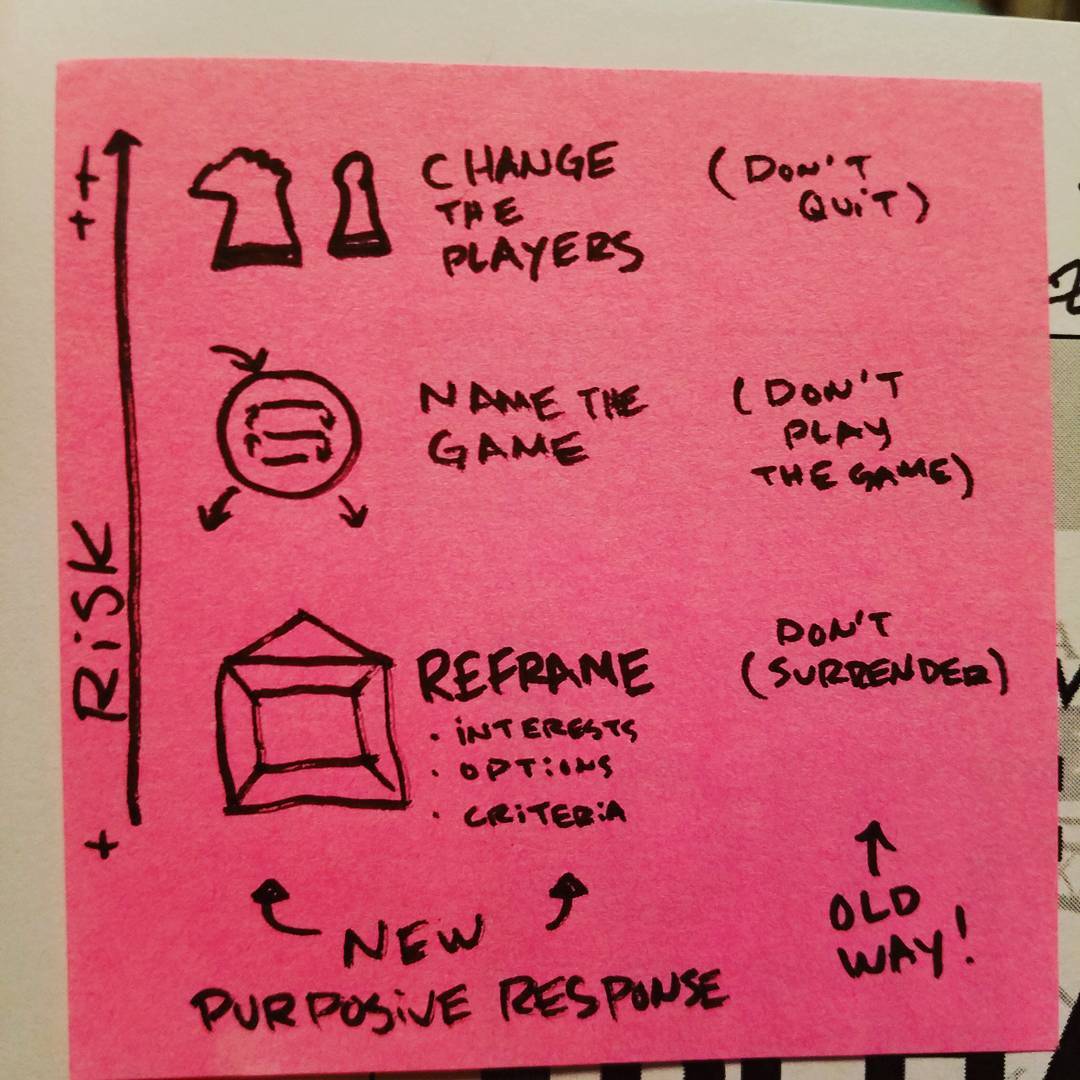

Daniel: But then there's this point where you have to stop listening to them, or listen to them less, and also explain to them why you're listening to them less, while you try to start a new conversation with the late majority. And that is a moment in every company's growth that is challenging. And I'm wondering what you can tell me about this, because I don't think many people think about that conversation shift that a product has to make.

Sarah: Yeah. That's very true. And its so interesting, I see it so much in the kick starter smart hardware. The entrepreneur crowd, I mean, because the other thing that I mention is that all of your product managers and your founders and whoever, they're all very much like your early adopters. That's the thing that makes it extra difficult. They're very similar in terms of mindset. They already see the promise of the product, they are more technically minded. They don't need an introduction to it, because they already are at some level, bought in. Whereas that late majority, they need a really nice introduction first before they can even begin the process of getting bought in.

Daniel: Yeah.

Sarah: And sometimes, that can be hard for your internal team to remember.

Daniel: Right. Well yeah, Snapchat didn't really explain itself a hell of a lot. And it wasn't designed for a 40 year old.

Sarah: Right.

Daniel: And then at some point, yes, where everyone's using it, and so they actually slowly evolved the interface to make it slightly more usable and less weird.

Sarah: They did. And they got some backlash for it from their users. I mean, that's one of the things that you have to deal with too, is that people will post scathing reviews about how you've dumbed it down and it's just no good at all anymore.

Daniel: So what do you do in that situation? It sounds like you had to face that, certainly at Belkin. How do you navigate that challenging moment?

Daniel: So what do you do in that situation? It sounds like you had to face that, certainly, at Belkin. How do you navigate that challenging moment?

Sarah: Well, it's not just one moment. It's a lot of moments.

Daniel: It's a constant barrage of moments.

Sarah: Yeah. I mean, obviously, data will help you. So in my talk, what I said was build bridges, and what I meant by that was really explicitly figure out how you're going to get in touch with that group that is outside the late adopter group. The group that is less likely, that isn't so vocal. And you have to be really specific about, "I'm going to do surveys in these places. I'm going to run tests on my packaging in these places. I'm going to do ethnographic research specifically like this."

Sarah: And then you also have to have access to the data that can keep you on course, because the early adopters are so loud. It's really easy to empathize with them and freak out. If someone writes some totally scathing review, it can be very easy for, especially for management or whoever, to say, "Oh my gosh, we have to fix this right now!"

Daniel: Yeah. And that may be right. The squeaky wheels do get the grease.

Sarah: The only way to avoid that is to have data to backup that that's not the majority. Whatever data that might be.

Daniel: Yeah, well that's an interesting thing. My friend Carl likes to say that the plural of anecdote is data.

Sarah: Yeah. So analytics, if your product is out live, some analytics will help you. And if you have ways to do larger scale tests in unfriendly markets ... That conversation begins with marketing and packaging. So that was something that we focused on a lot, was our packaging is selling to people who already know what we are, but it's not doing a good job of telling people who don't know "What we are what are we and what can we do for you," really quickly.

Daniel: So how does this change in this world where, you talked about the kick starter-ization of products, and I'm sure you in the internet of things, hardware, software, figital space. Seeing people who are just making another smart watch. Maybe they never want to cross into the late majority. There's a much ... Everything's becoming a niche now. Maybe more and more products don't have to worry about that late majority. Belkin was a very mass market product. Is Faraday Future, are you guys shooting for a niche, or a mass audience?

Sarah: The first car will most likely be niche, but the plans are for it to be sort of a brand gateway to more of a mass market. A set of products that might come later. And I hope I'm not giving away too much stuff there.

Daniel: No, no. I think that's certainly what Tesla has done. And that's sort of a reasonable strategy, but it sounds like at some point, you guys will experience a backlash then. Right?

Sarah: So the reason why this is problematic with hardware is because of manufacturing. So if your manufacturing costs are totally great for your margin at small scale, then more power to you. Then you can totally accomplish that. But when it comes to scale and hardware, a lot of things become profitable when you're dealing in a quantity that's large enough to offset your manufacturing costs.

Daniel: And most people do not realize this. That the difference between getting 100 things made and a 100,000, and a million, huge.

Sarah: Right. And so I think many of the people who are making hardware products now, they may be doing okay, but the margins are going to be smaller and you're not going to be making ... Usually, I mean, you're not going on speaking on generalities, but in order to make it so that you're at a comfortable income every month, is a challenge. You become really successful when you sell in large quantity. Just [inaudible] manufacturing.

Sarah: And this obviously might change. There are obviously all kinds of small scale manufacturing technologies that are coming up today that are totally changing this, and I think that's great. It's still not super widespread or necessarily quite affordable enough. And you'll see this actually, if you look a lot of kick starters for hardware. Even hardware that's not smart, even just things like bike bills and things like that that getting the manufacturing to the right level of quality and affordability and then stock quantity is a thing that everybody struggles with. It's a magic equation.

Daniel: Yeah. My first business was 3D printed jewelry using Shapeways, and that company was called GothamSmith, and what allowed us to ... Shapeways absorbed everything. They would print things on demand, and our costs were entirely fixed. It allowed us to make things that would be weird to make otherwise. But there are some things, like we had this key which was beautiful, but was way expensive. It was like $40 worth of metal because it was a bottle opener. To sell it as a necklace was ridiculous when people were going to thrift stores and buying old antique keys for like $5 in a big bucket. Or people were stamping them out of metal in China for $3.

Daniel: We were selling this ... We had to sell it for $80 because of the cost of materials was $40. So it just made no sense at all. So the four founders of the company, they still have them on their keychains but no one else does.

Sarah: Right.

Daniel: And so that's the limit of manufacturing cost scale.

Sarah: I mean, the other thing with smart hardware is of course the cost of sustainability. The more users you have, the more server fees you pay. And then if they're collecting years worth of data, or you're collecting their year's worth of data, how are you paying for that? And then all of the support, the back versions of firmware. There are a lot of hidden costs that really add up with it too that the product strategy really needs to think about those things up front. Those are all part of the "Let's make a product" conversion that needs to happen that are often things that you don't think about until it's late.

Daniel: Yeah. So there's two things there. Did you go, there was one of the lightning talks that was a bout death. I can't remember which day it was. So you think about zooming out on the timescale of a product, you're talking about the long use of the product and the cost overtime. And she was adding like, "By the way, there are people who have been long dead whose families are still using Facebook pages of the deceased as repositories for ongoing memories of these loved ones."

Daniel: And that was a huge ... I mean, that was an amazing talk. And amazingly lighthearted for being about death. So here's the thing, and this kind of shifts me into another question that I really had for you, was we talked briefly ... And also, your recommendation hits on this, that there are easy problems that you can solve with easy, obvious solutions, and then there's tough problems where there's no obvious ... There's many solutions and there's no conventional solution.

Daniel: And one of the things that I think is interesting is that in story telling, these simple scenarios inspire people. You're like, "Home automation is going to be amazing!" And then you can get bogged down in complexity.

Daniel: So it seems like you're talking about the same thing when you're like, "Oh, there's this cost of having the use over time, and they might die. And there's these all these servers and everything."

Daniel: So we get bogged down in complexity. Meanwhile, you want to make sure that I stay connected with these goals of user success. How do we ... There's these very two strong gravitational pulls. How do we navigate that?

Sarah: I don't know if I have an answer to that.

Daniel: That's okay.

Sarah: I mean, that's the crazy discovery process of this work that we do, right? Yeah.

Daniel: Well, I guess maybe the question that is possible to answer is what do you do for yourself to maintain both your creativity, but also your sanity in dealing with all of ... In navigating this complexity for yourself? Because obviously you're not at work all the time, but you think about work a lot. How do you step away, and what do you do to continue to be able to be a high functioning person?

Sarah: Oh. Lots of things. I mean, I think as designers ... I love people. So one of the things is that my goal is always that these things should help make people's lives better. So we need to, as a company, we need to make money. So we need to focus on trying to make that happen so that everyone who works there can stay happy, but also the end goal is when you do something that works great for someone else.

Sarah: And we would celebrate positive reviews for example, as a way to refocus the company around "This is why we're doing these things."

Sarah: And I think similarly, outside of work, spending time with people in the real world is really important. I have two kids, and talking to them, especially ... They're getting a little bit older now. Not that old, but nine and five, and talking to them about the way the world works. Talking to them about, for example, the semi autonomous car that I'm working on has been super fun. And seeing the questions that they ask about it, and how they are imagining it in their lives is always re-energizing.

Daniel: That's wonderful. I think being able to, and enjoying, explaining your work to people who are not in your work. My mother loves what I do. And I think she gets it. And that's really cool. To explain service design blueprinting to my mother, which I have done, and have her to be like, "You're right."

Daniel: Business is like ... To be able to see that spark go off in your mother's head, or your five year old son's head, and be like, "Oh, wow."

Sarah: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Daniel: When you said that you love people, that is a great way of reinvigorating your spark. Just sharing what you love about your work in the simplest way possible, which is really beautiful.

Sarah: Yeah. And also just paying attention to the way people act in the world even if it doesn't have to do with your thing specifically.

Daniel: Yeah. Well, yeah. This goes back to the designer always being a noticer. Observing.

Sarah: Yeah.

Daniel: What do you ... Are you a photo person? Do you absorb these little ... What details are you absorbing around the world? What amuses you when you're walking around?

Sarah: I sometimes take photos, but not always. I'm mostly just look at things and then think about them, and then find someone I can tell about it.

Daniel: So is it like what, there should be no confidential issues for this one, I hope. Is there something recently that you're like, "Well, hell. That is just crazy."

Sarah: You mean aside from politics?

Daniel: Yeah. Well, we could just spend a whole nother hour talking about that. Yeah, no. In the sort of-

Sarah: So that's taking a lot of my mental space lately.

Daniel: Oh, it sure is.

Sarah: I mean, and actually, well. I don't know how relevant this is to the conversation, but as a part of that, I was reading an economics article about populism and about how technology relates to populism. Specifically, actually, automation, and how that is impacting our job market. So I've been thinking a lot about how people interact with automation lately. That, and also how people need work. How people really enjoy productive, meaningful work, and the sort of tension between those two things has been something I've been thinking about a lot lately.

Daniel: Yeah. I mean, it's weird making ... Every time I get into an Uber, and I haven't deleted Uber because I haven't, but I love talking to my Uber drivers because they're always such interesting people. If you get into an uber or Pittsburgh or Chicago or Singapore, you hear a great story. And everyone I talk to, I think to myself, "What's going to happen when this is a fully autonomous car?"

Sarah: Yeah.

Daniel: These people who have been picking up extra money and have enjoyed the flexibility and are being able to pay off their lease on their car, I definitely have that question where it's like, I don't think Uber is going to pay a tax to transition these people into a new form of work.

Sarah: Right.

Daniel: And that is a real thing.

Sarah: It is a real thing. And I feel like it's something that we as designers who work on technology, should be thinking about. I don't have any answers for it for sure, but I think that the way that our work impacts people who aren't actually just our users I think is really important. And I feel sort of surprised that I actually haven't been spending as much time thinking about it, because [inaudible] that I've started thinking about it so much now, but haven't before. So in retrospect, it's sort of surprising to me.

Daniel: Well, you know, that's a really great question because I think in the design school I went to, Pratt in New York, I definitely started to see, when I would go back over the last ten years for thesis presentations, more and more people becoming more socially aware in like, "What are we making? Why are we making? Should we be making anything? Aren't there enough things already?"

Daniel: I think design is waking up. So I wouldn't be so hard on yourself. I think as a young designer, you do it because you love making stuff and you love helping users in solving problems. And then you begin to realize-

Sarah: Right. Not just products but I think technology as a whole, right? I think it's easy for this sort of Silicon Valley, even New York City, that mindset of like, "Well, technology is great. Technology can save the world. Technology is such an overwhelmingly positive force." But just to think about the greater society and humanity that it resides within, and the fact that it maybe isn't always.

Daniel: So that leaves me with my last index card, which was from the last five slides you had, which was about just giving more love. And you took hearts and you put them over most of the issues, like how do you give more love to all of these things? What does that mean for you? What does giving more love in this context mean?

Sarah: Right. So I said briefly in my talk, what it means to me is focused attention and committed engagement. I mean, that sounds like love, right?

Daniel: Yeah. That is love, yeah.

Sarah: You know. It means showing up and paying attention, and having conversations that might not be easy conversations, and not taking your eye off those things. In any of those examples, engaging more and prioritizing more around that topic would be helpful. And giving it any of the energy that you can find, whatever that might look like.

Daniel: Yes.

Sarah: So I wasn't super prescriptive about, "These are the five activities you should do."

Daniel: Yes, yes.

Sarah: But in general, I think paying attention, empathizing, communicating, and acting. All of those things together.

Daniel: That's really ... I mean, that is just so simple but I'm going to have to say, when you were talking about the meeting structure, when you're navigating framework versus details and really hearing somebody, and making them heard before you say yes or no. Just saying yes by listening to them, but then making up a concrete action that shows evidence that puts your money where your mouth is, you say. "I'm hearing you, and put that In JIRA." And guess what? If you keep telling that person, "I hear you, and put that in JIRA," and it never makes it in a release, what do you think they're going to ...

Daniel: Eventually, they're going to be like, "I never get it into the release." Well, you need to eventually actually take real action.

Sarah: Right. I mean, hopefully, those things come up for conversation at every spring planning. That you say ... You talk about the reasons for, and the reasons against, and you talk about what the overall goals are. And then we definitely had moments where we realigned our goals, because we realized that we were constantly leaving out a certain group of things that a lot of people felt were a priority, but that due to our current structure, weren't making it into any release. And we said, “This is a thing that's happening, and we notice it, and we need to find out why and to restructure our goals to make sure that we get some more balance of this consideration."

Daniel: So this adaptive cycle is really important, and I think you see it in one on one conversations, and you see it in team conversations. It's really good to hear you talk about that.

Sarah: Yeah, it's super important because none of these things are a solution, they're all process.

Daniel: Yes.

Sarah: They all, you need to come back to them and rework them, and continually pay attention to them.

Daniel: So Sarah, the hour has just flown by. It is an absolute delight to talk to you. I would like to ask you my favorite question, which is, is there anything I should have asked you that I have not asked you?

Sarah: No. I mean, I don't know about should have.

Daniel: Well, is there anything else you'd like to share around these topics that we haven't hit on?

Sarah: I mean, I'm particularly, to backtrack a tiny bit, I'm particularly interested in how automation, in terms of simple automation, like in your home, how that really needs to actually have more conversation built into it. How there's this sort of an idea that, "Oh, this product can now do this thing for you." So it's just going to do it for you, is actually really flawed. And instead, it actually needs to act more like a person, then. If it's going to behave like a person and take care of something for you, then it needs to actually communicate with you like a person.

Daniel: Yes. Oh yes, we didn't talk about that at all. So yeah, this is the ... I finally read that Easy Hard article, and he talks about the, "Okay, so when I walk into the room, the light will go on. That's easy. But wait, my wife is in bed sleeping, so okay, well, sensors to detect that she's in bed."

Sarah: Right.

Daniel: And then it's like, "Oh, well, there's a dog sleeping on the bed. But I still want the lights can go on because I don't care about waking up the dog."

Daniel: And then, "My wife is lying on the bed watching TV, and I want the light to go on when I walk in."

Daniel: And the solution is, "Read my mind."

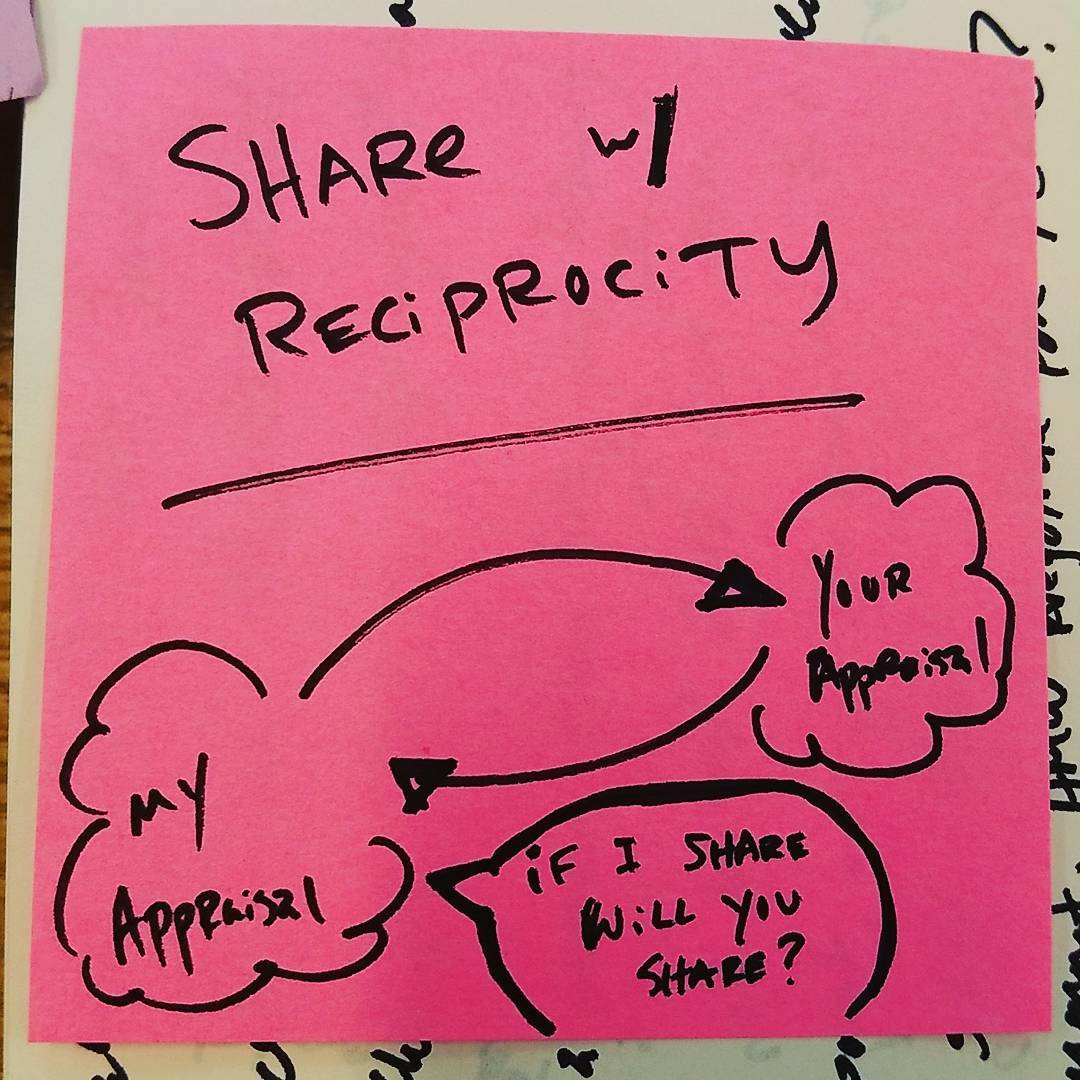

Sarah: Right, exactly. So you and I also talked in person, we talked a little bit about the nest for example. Where the nest just said, "Oh, I've just figured everything out for you, and I'm just going to do it. But I'm not going to tell you about it, nor am I going to allow you to ask me about it. I'm just going to do it, and you don't get to know."

Sarah: If a person did that, you'd be furious. So I think that the more of that consideration of, if something's going to take agency on your behalf, it has to be able to communicate with you in a way that ... Sort of a similar way that you would expect for a person who takes agency on your behalf.

Daniel: Yes.

Sarah: Does it tell you before? does it tell you after? "Oh hey, I did this thing for you." And definitely, if you ask it, "What did you do?" It should be able to tell you.

Daniel: Yes. So right, I actually have this as a card which I was going to leave, because I didn't want to push too hard on this, but yeah. An agent is somebody you say, "Can you just go do this?" And then they do it. And something that has agency, there's more ... We talked about the ramp of trust. You give more trust to that thing, and they handle a lot of stuff in the background for you. How does that ramp of trust, how does this agent, this digital agent, build that trust?

Daniel: That's what you're talking about there, that conversation that this digital agent is willing to have with me. To say, "Hey, I'm going to go take care of this thing for you. Is that cool, boss?"

Daniel: And you go, "Sure, absolutely."

Sarah: Yeah. I mean, I think a lot can be learned from the way that people do that same interaction, which is that idea of first, I notice that you do this thing, and I tell you, Hey, I notice that you do this thing."

Sarah: And then I say, "Do you want me to set it up so that it will be like this?"

Sarah: And if I say no, then you might say, "Well, why?" Or you might try again later.

Sarah: And if I did do it for you, then I reassure you, and I say, "Hey, just so you know, I did this for you."

Sarah: So that you don't wonder, "I told you to do it, did it do it?"

Sarah: And then you offer ways for people to check. If past all of that, they have this question, "Hey, did you do this thing?"

Sarah: My favorite thing is that a lot of the smart home ... People have this moment where they're like, "What is happening right now?" Because the system is behaving in some way that is impenetrable, and you have to be able to have an answer to that question. What is happening right now? You have to have an answer that is easily provided.

Daniel: That is actually so interesting. It's almost like ... I'm a PC user, so I don't know if you even know what I'm talking about, but if you ... On Mac, there's a task manager. You can just see what programs are running. Like, "Why is my computer fan going at a million miles an hour and everything's hot?"

Daniel: You're like, "Oh, right. It's because Skype has decided to use 90% of my resources." That's something that I want to be able to do. Check my email.

Sarah: Right. Because if you can't get the answer to that, then you figure everything is possessed or crazy, or broken. And then it has lost all your trust.

Daniel: Right. Well so, then this brings the question up, because we talked about Clippy last time, which you described as oversold or over-scoped. Because, "I can do everything!" How do these agents become more like Alfred in the Batman? Where deeply trusted, deeply capable, but obviously some things he knows he's not good for. He's not going to actually fight the Joker, ideally. There are limits.

Sarah: Yeah. I mean, some of it comes down to personality. Clippy's personality was just completely all wrong. But then yeah. I mean I think it is about scope. You wouldn't pick some stranger up off the street and then suddenly have them manage everything about your life. You would start small, and you would double check on it, and then you would slowly begin to trust it, and then you would maybe expand from there with constant checks.

Sarah: Like I said, any time when trust is lost, then you have to be able to scale back without ... And/Or investigate why something went wrong.

Daniel: So this is still a big burden, because in the Easy Hard article, he talks about a voice system that as a 10% failure rate, is really frustrating to work with.

Sarah: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Daniel: And we have a very quick level of like, "Wait, this doesn't do everything? This thing is dumb." Response.

Sarah: Right. But everything ... Yeah. I mean, there, because the boundaries aren't clear with a voice. With voice, through the promise is, "Oh, it can talk to me." So you don't expect it to be able to turn on the washing machine by itself necessarily, or buy milk. But you do expect it to be able to talk to you. So its boundaries and what it can do that are narrow, are narrow in ways that aren't super clear.

Daniel: Yeah, because people love asking Alexa to tell them a joke.

Sarah: Right.

Daniel: Or the, I think one of the talks was about Alexa versus Siri when you say, "Siri, do you know my husband's name?"

Daniel: And then Siri's like, "No, you haven't told me that yet."

Daniel: And Alexa says, "I'm concerned that you don't know."

Sarah: Yeah.

Daniel: And those are two ... When you talk about personality, those are two really different personalities.

Sarah: Yup.

Daniel: The analogy I often use is, I don't know if you're a comic book fan, or if you've watched the Avengers movies, but at one point, he's got Jarvis who's running the Iron Man suit. And Jarvis is this English butler that he's programmed, and at one point, Jarvis breaks, and he gets Friday, which is this plucky 1950s newspaper reporter gal. It's like, "Right on it, boss! I'll get that for you!"

Sarah: Right. Yup.

Daniel: And I don't know which personality people want. My girlfriend calls her Alexa echo, because I think she thinks it's vaguely sexist to have it be her female slave. So how would you navigate that Scylla and Charybdis of all these personality requirements that people have?

Sarah: Well, I mean, obviously, getting feedback is important. I mean, picking one that you can establish some branding around and really focusing on making that one as appropriate as possible, I think is really important to start out with. Because if you just go out with just a huge wide array that people can choose from that people don't really know, and it also makes it harder on the team to make sure that they all are really great.

Sarah: So picking one ... I mean, I mentioned that branding and that sort of emotional design, that affection development between your product and your users, is really important and can really help you in cases where something might go wrong.

Sarah: So those things just have to be tested, and tested, and tested. Because people internally might think one thing, and then ...

Daniel: Yes.

Sarah: They might be wrong.

Daniel: So this is very interesting, because I was talking with Paul Pongaro earlier this week, who gave a talk on conversation design at the IXD conference. We talked about conversation design as a manipulation, right? And that there's both good and bad connotations to manipulation, but when you're talking about building capabilities into an agent to allow me to trust it, you're manipulating people to feel a certain way about it by giving it a certain personality, certain relationship building skills. You are making this thing that is going to manipulate us, and that's a very ... That's a heavy responsibility.

Sarah: It is. But you're playing within the bounds of social behavior.

Daniel: Yes.

Sarah: I mean, obviously, you're not trying to make it lie or [inaudible 01:01:32]. Not disclose its taxes or something, but you're ... You know-

Daniel: The American people don't care, by the way.

Sarah: No. In every conversation that you have with another human being, I mean most human beings, they modulate their responses in a way to either fit norms, or to put you at ease, or to just not be weird, essentially.

Daniel: Yeah, you're right.

Sarah: And so hopefully, as long as you have sincerity behind the things you do to try to facilitate the best kind of conversation you could have, I don't think you're really in ethical gray territory. You're just being social.

Daniel: Yes. I want to celebrate the word you just used, because sincerity is such an interesting word, I think. I've been having some conversations about conversations where authenticity comes up, and it's a very ... Especially around brand people, they're like, "I don't want to talk about authenticity anymore." It's like it's a very tired word. But sincerity is a very human word, and I think there's something really lovely about that, that particular choice.

Sarah: Yeah. Me too, and I think people have fairly strong sincerity meters.

Daniel: Right. And the designer behind it being sincere, the relationship between the company and the person not being overly extractive, right?

Sarah: Yeah.

Daniel: And so that's something where that is all about building trust. That Amazon, Alexa's not going to buy something without you understanding what you're buying. And you can return it if they did. So that kind of transparency and trust is definitely a part of that agency. That trust that you give to that agent.

Sarah: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Daniel: Which is really cool. Well, that is a really ... I'm glad you brought that up, I'm glad we talked about it. I think we're out of time. I really appreciate you giving me your time, this is a real ... We touched on some really great stuff. I will include your talk, both the medium article and the slides in the episode notes, and I just really appreciate you talking the time to talk about some of these topics because I find them very essential for our times.

Sarah: Yeah. It was totally my pleasure. I really enjoyed it.

Daniel: Awesome. Thank you so much, Sarah. Have a great weekend!

Sarah: Thank you! You too!