Buckle in, ladies and gentlemen, for some straight talk about the future of work, the nature of the universe and the power of changing systems to change behavior.

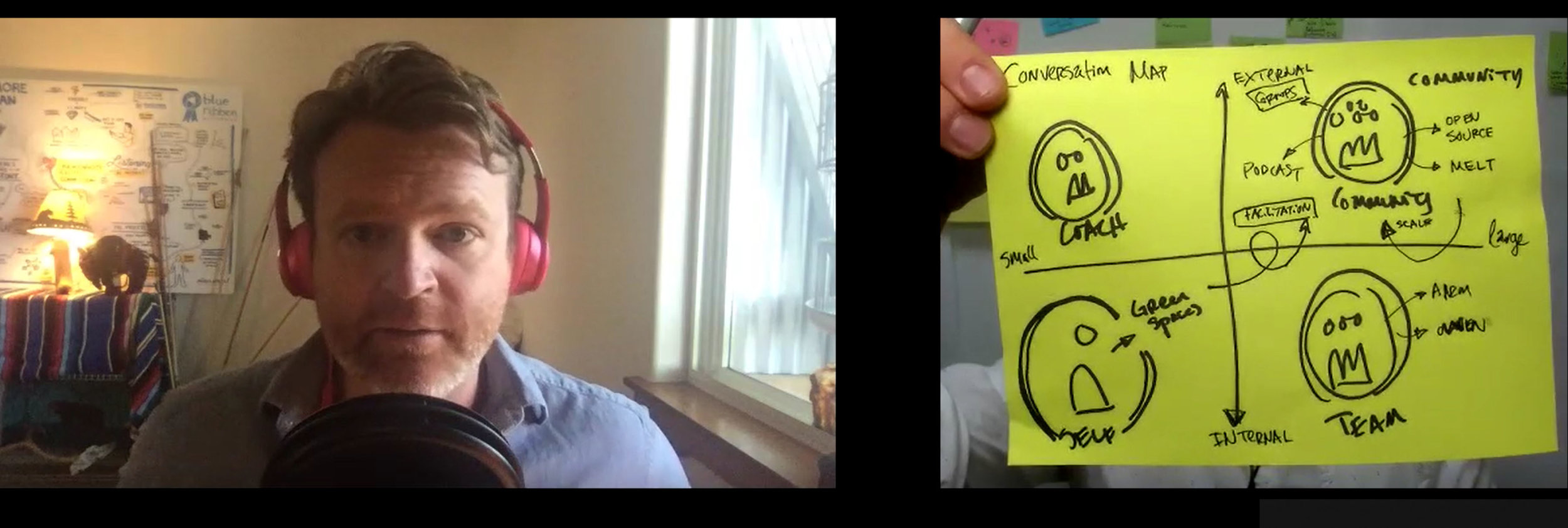

Today I’m sharing a deep and rambling conversation I had a few months back with Aaron Dignan, author of Brave New Work and founder of the Ready, an org transformation partner to companies like Airbnb, Edelman and charity: water. He is a cofounder of responsive.org, an amazing community of like-minded transformation professionals. If you haven’t checked out their conference, it’s great. I co-facilitated some sessions there last year and I can highly recommend it. You should also check out the episode I had recently on asking better questions with Robin Zander, who hosts the conference.

http://theconversationfactory.com/podcast/2019/4/23/robin-p-zander-asking-better-questions

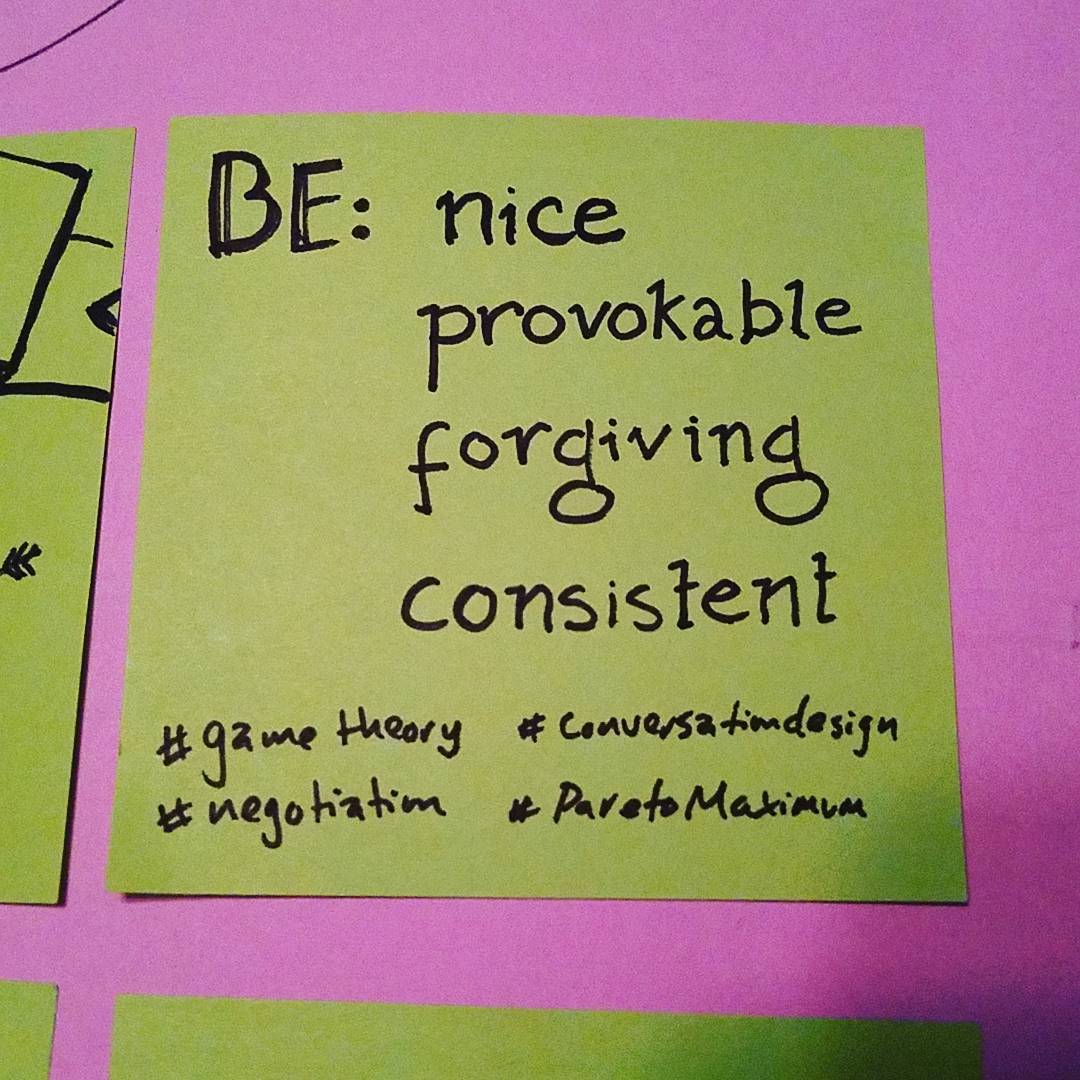

I owe a debt of gratitude to Aaron. It was his OS Canvas, published in 2016 on Medium, that got me thinking differently about my own work in Conversation Design and led me to develop my own Conversation OS Canvas. His OS Canvas clarified and simplified a complex domain of thinking – organizational change – into (then) just nine factors. In the book it’s evolved into 12 helpful prompts to provoke clear thinking and to accelerate powerful conversations about how to change the way we work – if you are willing to create the time and space for the conversation.

Aaron doesn’t pull any punches – as he says, “the way we work is badly broken and a century old”. And he figures that “a six year old could design a good org, you just have to ask the socratic questions.” His OS Canvas can help you start the conversation about changing the way you work in your org and his excellent book will help you dive deep into principles, practices and stories for each element of the OS.

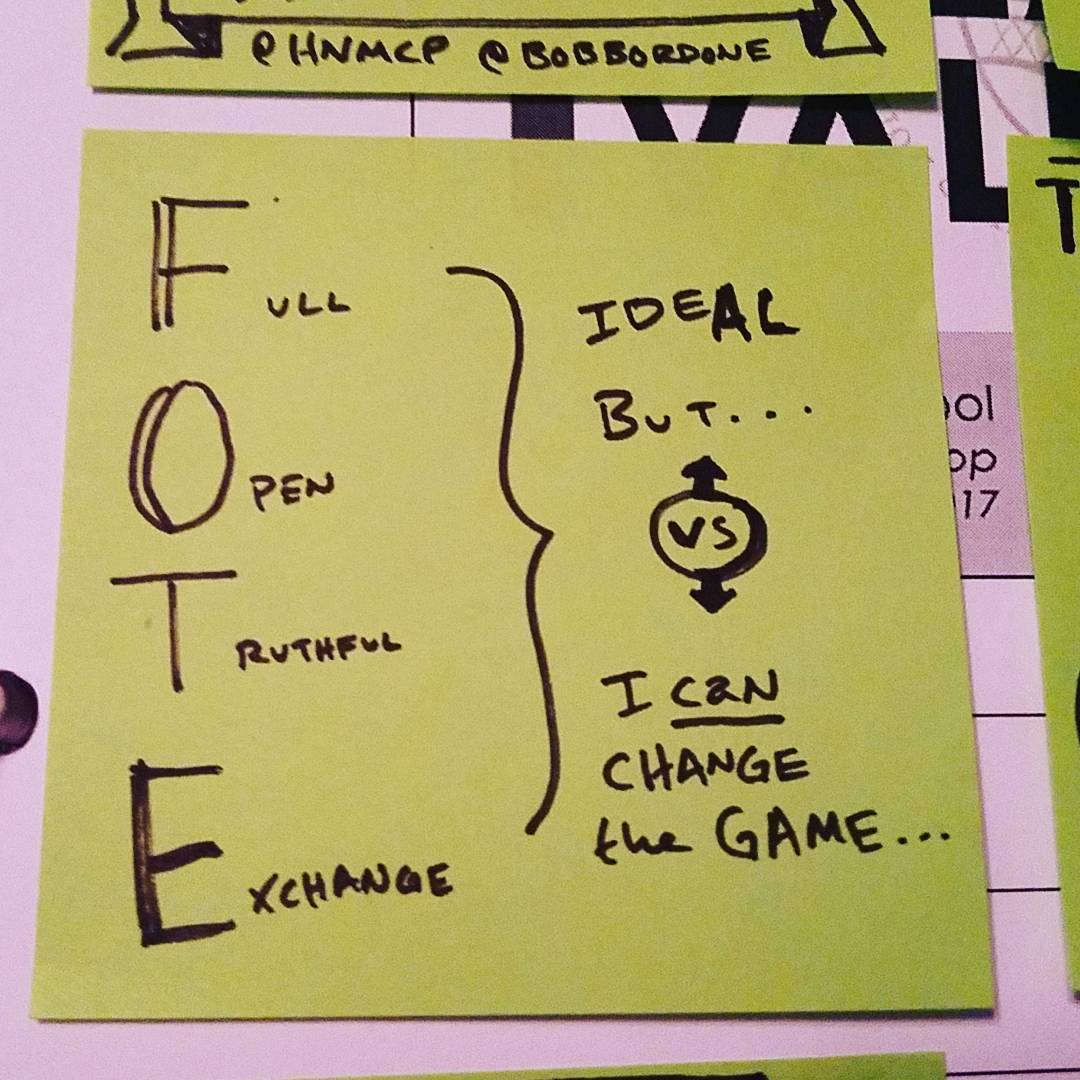

You’ll find in the show notes some deep-dives on the two core principles of org design from the book. The first principle is being complexity Conscious. The second is being people positive. For more on complexity – dig into Cynefin (which is not spelled the way it sounds). And for more on people positivity, there’s a link to Theory X vs Theory Y, a very helpful mental model in management theory.

Another powerful idea that I want to highlight is Aaron’s suggestion that we all have our own “system of operating” or “a way of being in the world” which is “made up of assumptions and principles and practices and norms and patterns of behavior and it's coded into the system.”

Aaron goes on to say that “people are chameleons and people are highly sensitive to the culture and environment they're in. And the system, the aquarium, the container tells us a lot about how we're supposed to show up. And over time it can even beat us into submission. And so we have to change the system and that's hard to do when we're reinforcing things that we ourselves didn't even create,”

From my own work on conversation design, it’s very clear to me that communication is held in a space, or transmitted through an interface – the air, the internet, a whiteboard. The space your culture happens in is one very key component of how to shift your culture. Check out my episode with Elliot of Brightspot Strategy for more on changing conversations through changing spaces:

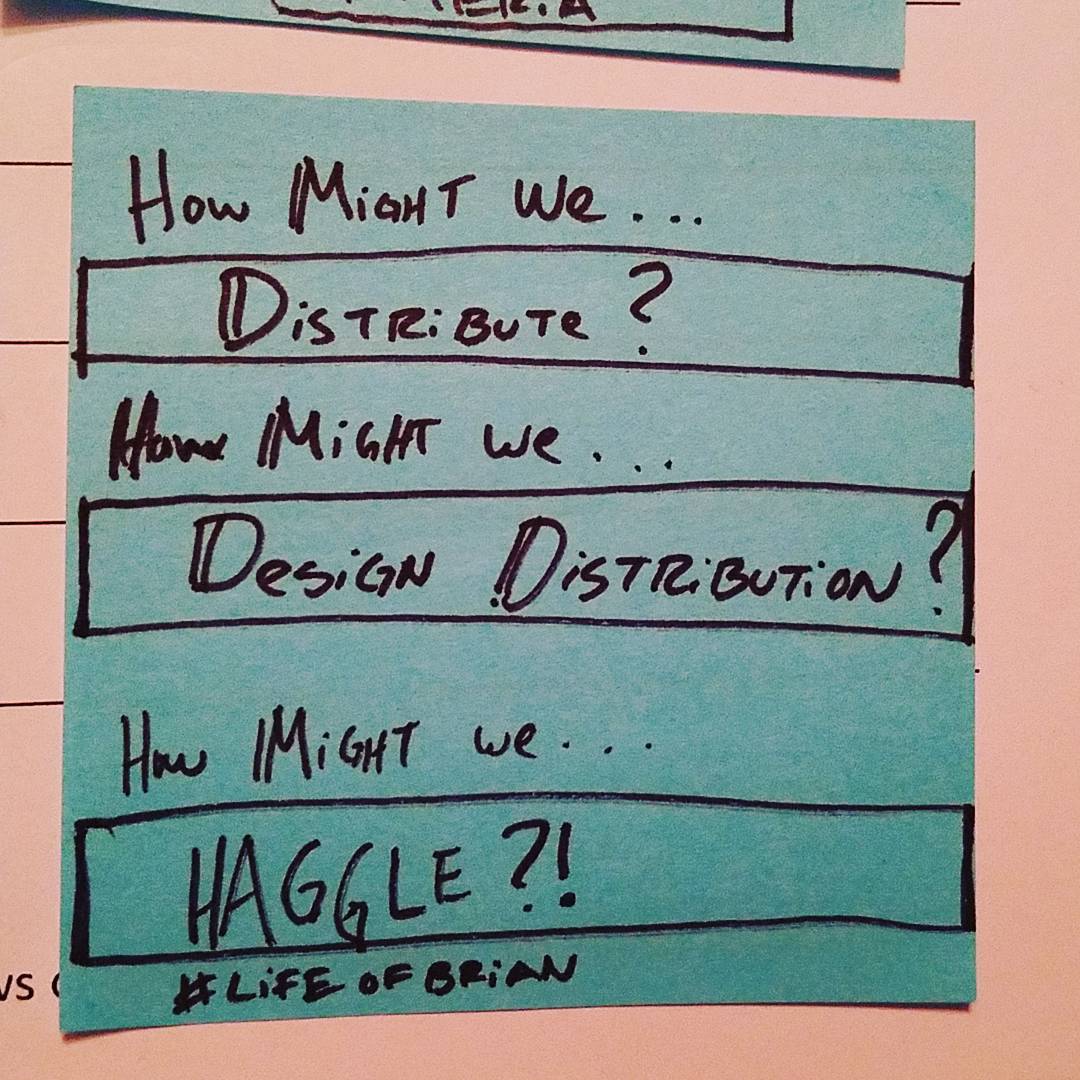

Changing your physical space is easy compared with shifting power and distributing authority more thoughtfully in your organization. To do that, we need to shift not just our org structures, but our own OS: we need more leaders who can show up as facilitators and coaches rather than order-givers. And that takes, as Aaron points out, a brave mindset.

If you want to become a more facilitative leader of innovation and change in your company, you should definitely apply before August to the first cohort of the 12-week Innovation Leadership Accelerator I’m co-hosting with Jay Melone from New Haircut, a leader in Design Sprint Training. It kicks off in NYC with a 2-day workshop in September, runs for 12 weeks of remote coaching and closes with another 2-day workshop. We’ll have several amazing guest coaches during the program – a few of which have been wonderful guests on this very show: Jim Kalbach, author of Mapping Experiences and head of Customer Success at Mural and Bree Groff, Principle at SY Partners and former CEO of change consultancy NOBL.

Show Notes

The OS Canvas Medium post that started it all for me:

https://medium.com/the-ready/the-os-canvas-8253ac249f53

The Ready

Brave New Work

Complexity Conscious: Cynefin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cynefin_framework

Being people positive: Theory X vs Theory Y

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theory_X_and_Theory_Y

Capitalism needs to be reformed: https://www.cnbc.com/video/2019/04/05/capitalism-needs-to-be-reformed-warns-billionare-ray-dalio.html

The Lake Wobegon Effect

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_Wobegon

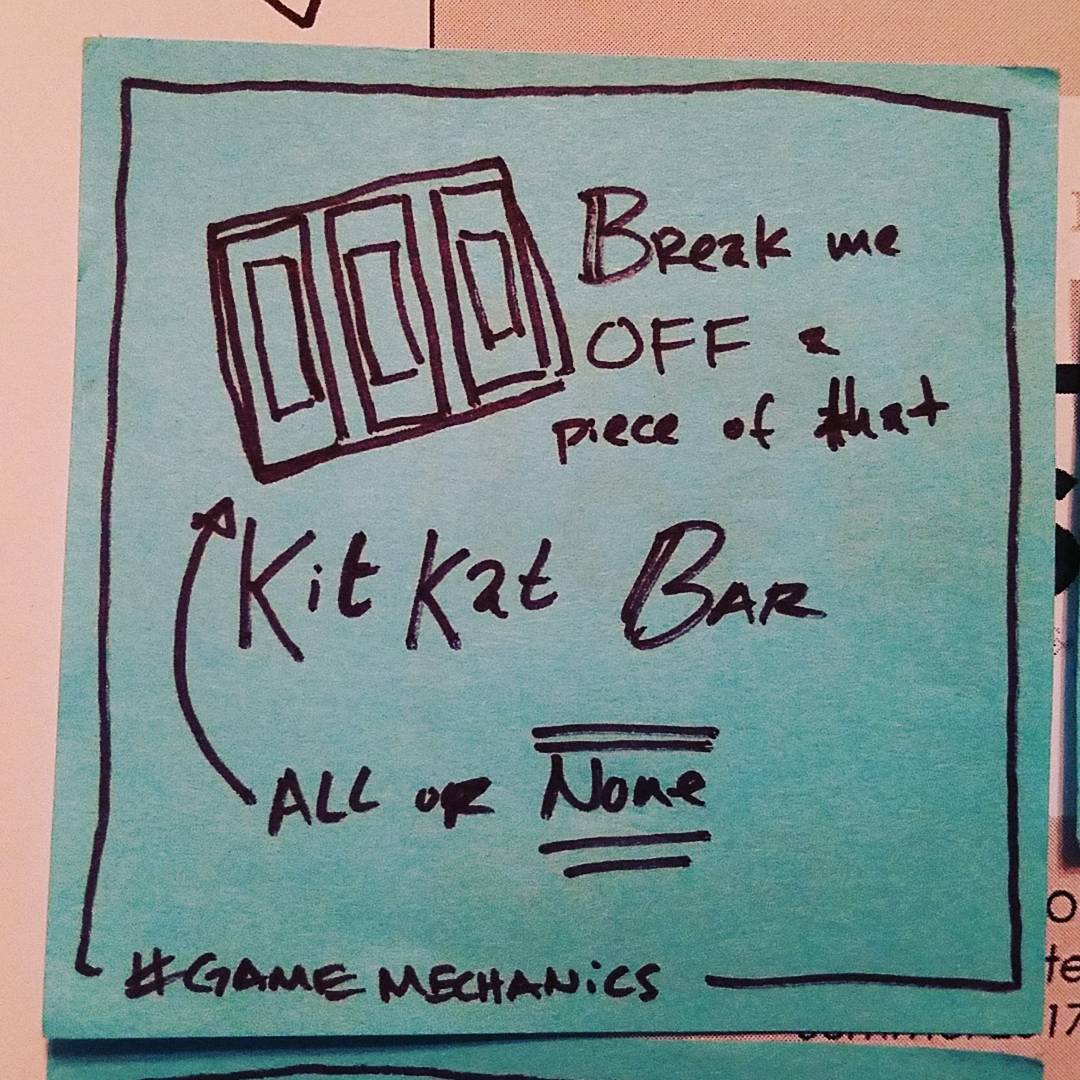

Game Frame

https://www.amazon.com/Game-Frame-Using-Strategy-Success/dp/B0054U5EHA

The Four Sons as four personalities at work in us:

https://reformjudaism.org/jewish-holidays/passover/which-four-children-are-you

MECE

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MECE_principle

Fish and Water:

https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/97082-there-are-these-two-young-fish-swimming-along-and-they

The Finger and the Moon:

https://fakebuddhaquotes.com/i-am-a-finger-pointing-to-the-moon-dont-look-at-me-look-at-the-moon/

also from Amelie!

https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/am%C3%A9lie

Zen Flesh, Zen Bones

https://www.amazon.com/Zen-Flesh-Bones-Collection-Writings/dp/0804831866

Agile

Open Source Agility: http://theconversationfactory.com/podcast/2017/6/23/dan-mezick-on-agile-as-an-invitation-to-a-game

The Heart of Agile

Lean

https://www.lean.org/WhatsLean/Principles.cfm

Open

https://opensource.com/open-organization

Information Radiators

http://www.agileadvice.com/2005/05/10/bookreviews/information-radiators/

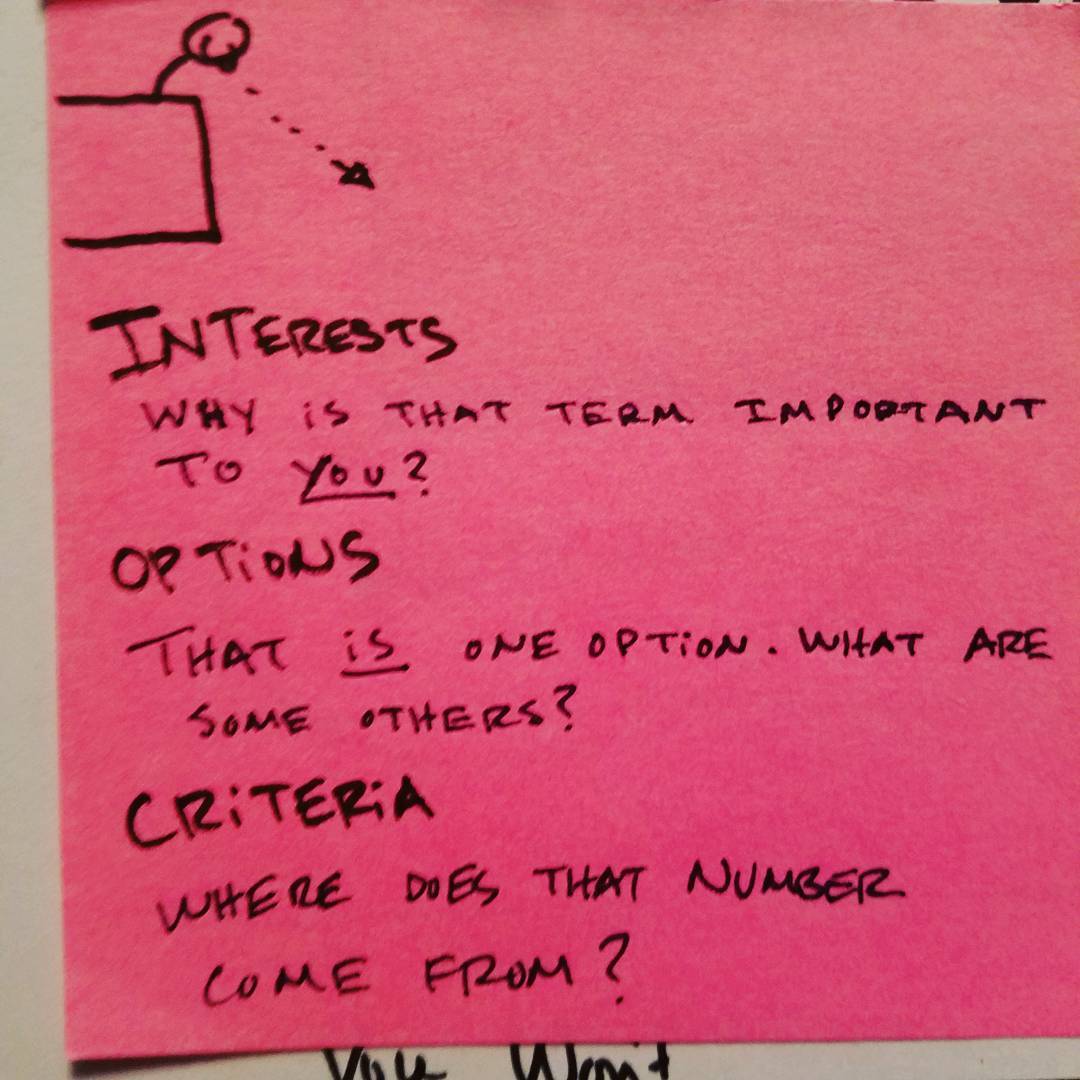

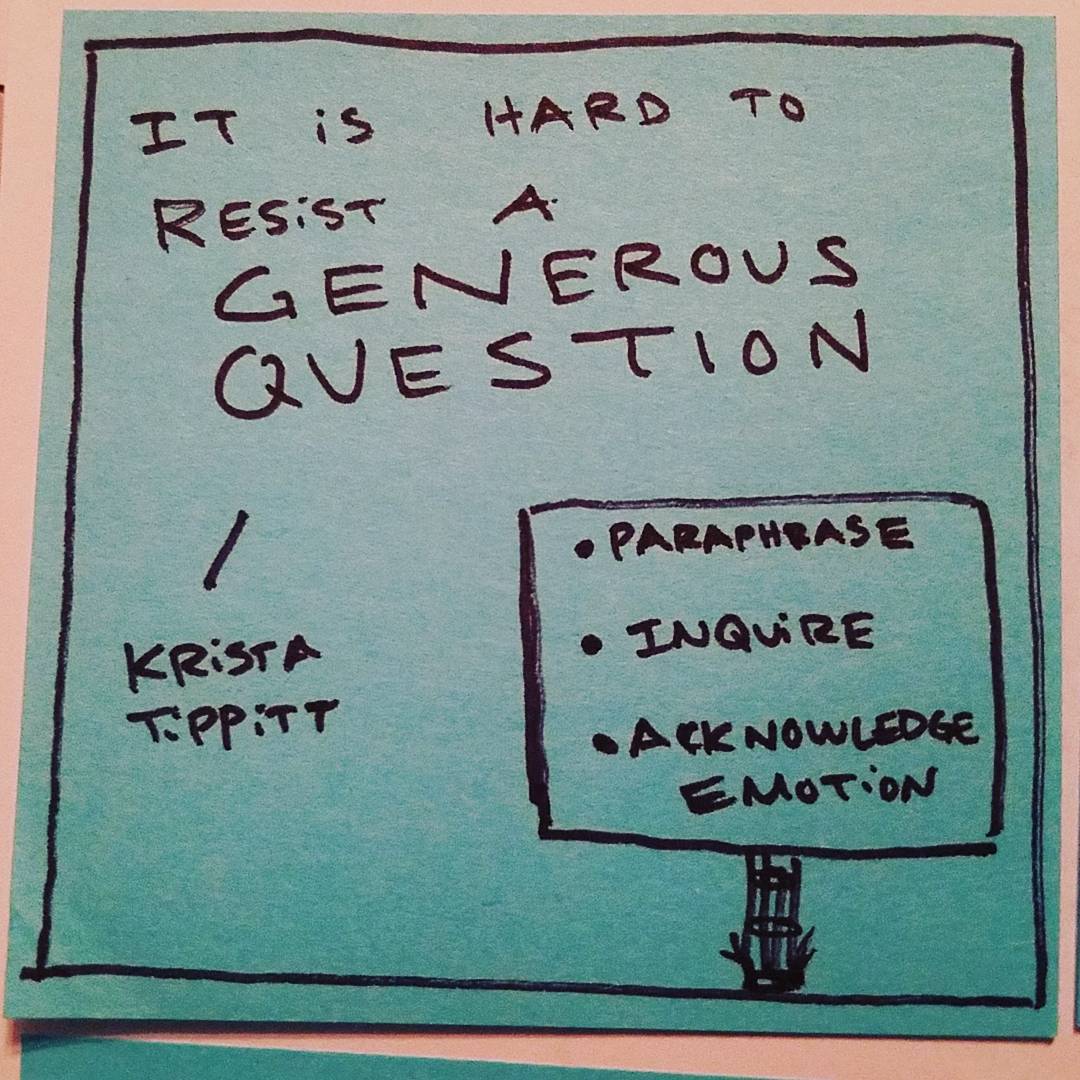

Asking better questions:

http://theconversationfactory.com/podcast/2019/4/23/robin-p-zander-asking-better-questions

Loss in Change:

http://theconversationfactory.com/podcast/season-three/bree-groff-grief-and-change

Mapping experiences:

http://theconversationfactory.com/podcast/2018/2/5/jim-kalbach-gets-teams-to-map-experiences

Interview Transcript:

Daniel: So I'll officially welcome you to the conversation factory. Aaron. I really do appreciate you making the time to do this. You are in the long, you're in the long tail of your sprint, getting your book out into the world,

Aaron: ...almost there, almost there, and happy to be here. This is going to be fun.

Daniel: Thanks man. I mean obviously like I think back to like when I met you and we're like sitting in the park and...

Aaron: Yeah, you had an instrument of some kind?

Daniel: yeah! ....And you had this dream, like you were building this new thing and you're like, I feel like you've just crushed it .... in the most beautiful nonviolent way of crushing it, building this thing.

Aaron: Well, it looks good from afar. It's actually been, you know, difficult and fun and challenging and you know, up and down. But uh, it is, it's working. It's, we're doing the work that we want to do in the world.

Daniel: Yeah. And so like that's ... So I think that's actually a great transition because like the call to action on your book is strong. Like it's like, are you ready to change your organization? Like I could see how this is pushing out the idea that you're really passionate about. That's what this book is about, is trying to like, get people to say like, yeah, I am ready to do that. Tell me how!

Aaron: we had a, we had a big debate actually at the, at the publisher about, you know, what's the right subtitle for the book. And obviously as you're alluding to the message of the book is that, you know, the way we work is, is badly broken and, and, and you know, in most cases a century old and needs to be changed. I'm to something more adaptive and more human. But um, but the question of how to say that was, was really a challenge. So we tried all these different subtitles that they all felt like sort of traditional business bookie, sort of titles, you know, ditch bureaucracy and change your life forever. It Dah, Dah, Dah, Dah, Dah, Dah

Daniel: "A five part manual to blank, blank, blank, blank and blank."

Aaron: Exactly. And then someone said, why don't we just do a question? Like no one's done a question as a subtitle in a long time, why don't we do that? And then it became really clear because you know, the work is, is curiosity led. It's about questions. It's about asking yourself things we don't always ask ourselves. So it was cool to start with, are you ready to, to reinvent your organization? And you know, for most people the answer might be no. But for a lot that I run into the answer is hell yes.

Daniel: Yeah. And you're definitely this rallying cry like, and then here's the tools, here's how to do it.

Aaron: Right, right. Here's the way to start at least. I mean, I think one of the, one of my big goals with the book is not necessarily for everybody to have some "from to" journey cause I don't think that's what it's about, but it's really just about like, you know, are you ready to start being more deliberate and more considered in the way you work as an individual, as a team member, as a founder? Like are you willing to sort of take this stuff seriously?

Daniel: Well, so this is, I didn't actually think I would start this conversation this way, but like I think one of my theses in, in looking at things through the lens of conversation is that conversations are organic, ongoing and iterative. And as opposed to, you know, one that's mechanistic...

Aaron: They're not speeches

Daniel: yeah, they're not speeches. And in a way like starting with the question is starting the conversation of like, well are you ready to start changing your organization and what does that mean and how do we start and what does it look like and what does done mean? Does done ever happen? Like it seems to me that changing the organization is, is a conversation.

Aaron: Absolutely. And I mean in many ways an organization is nothing more than a set of conversations. Right? Like the, the main, the main fuel that flows through any gathering of people is communication.

Daniel: Yeah. It's like a bundle of like, I think of it as like a topography, like, uh, you know, like water flows and certain valleys in and other places. And it's like, so this gets to the question of like, what can you change about the topography, right? What's changeable?

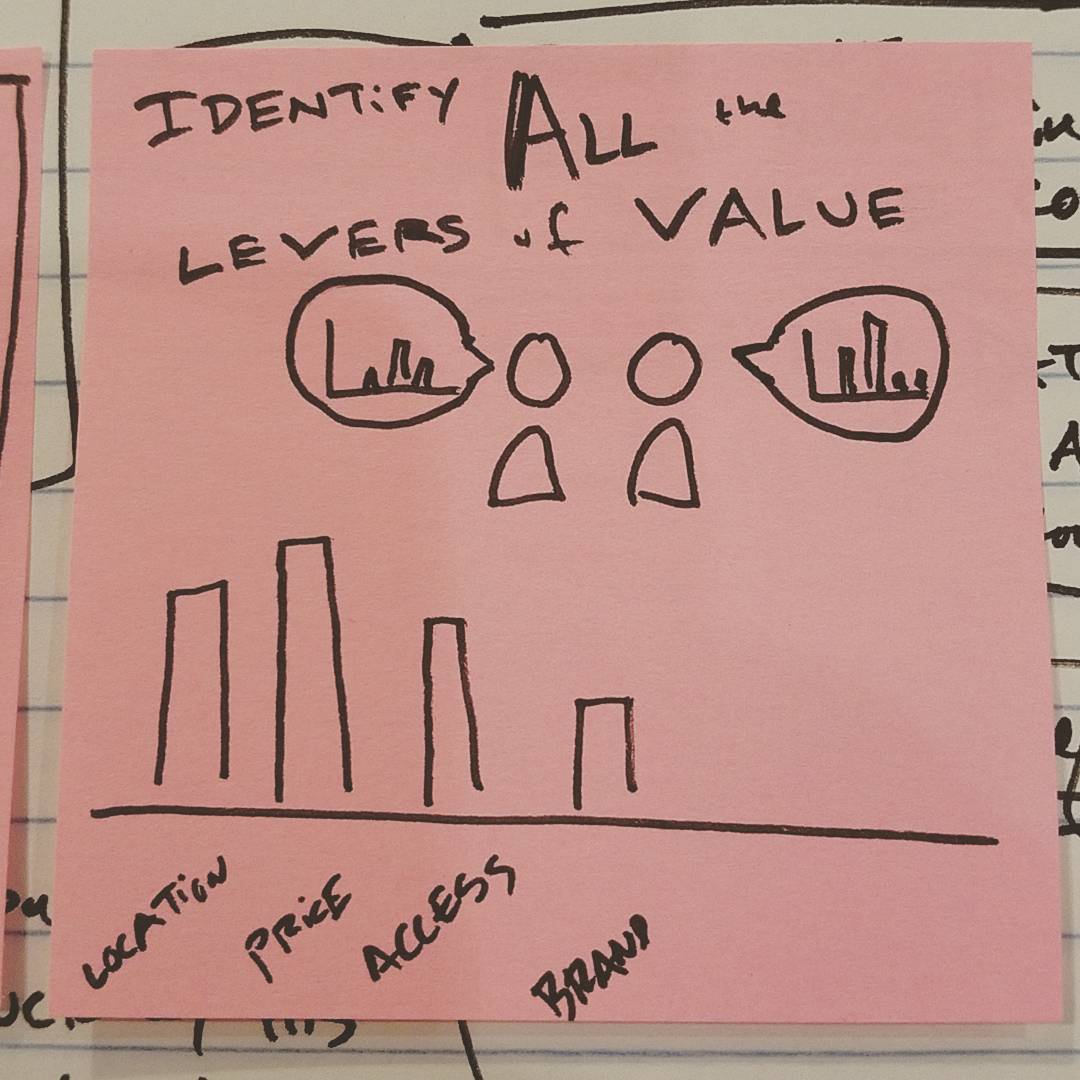

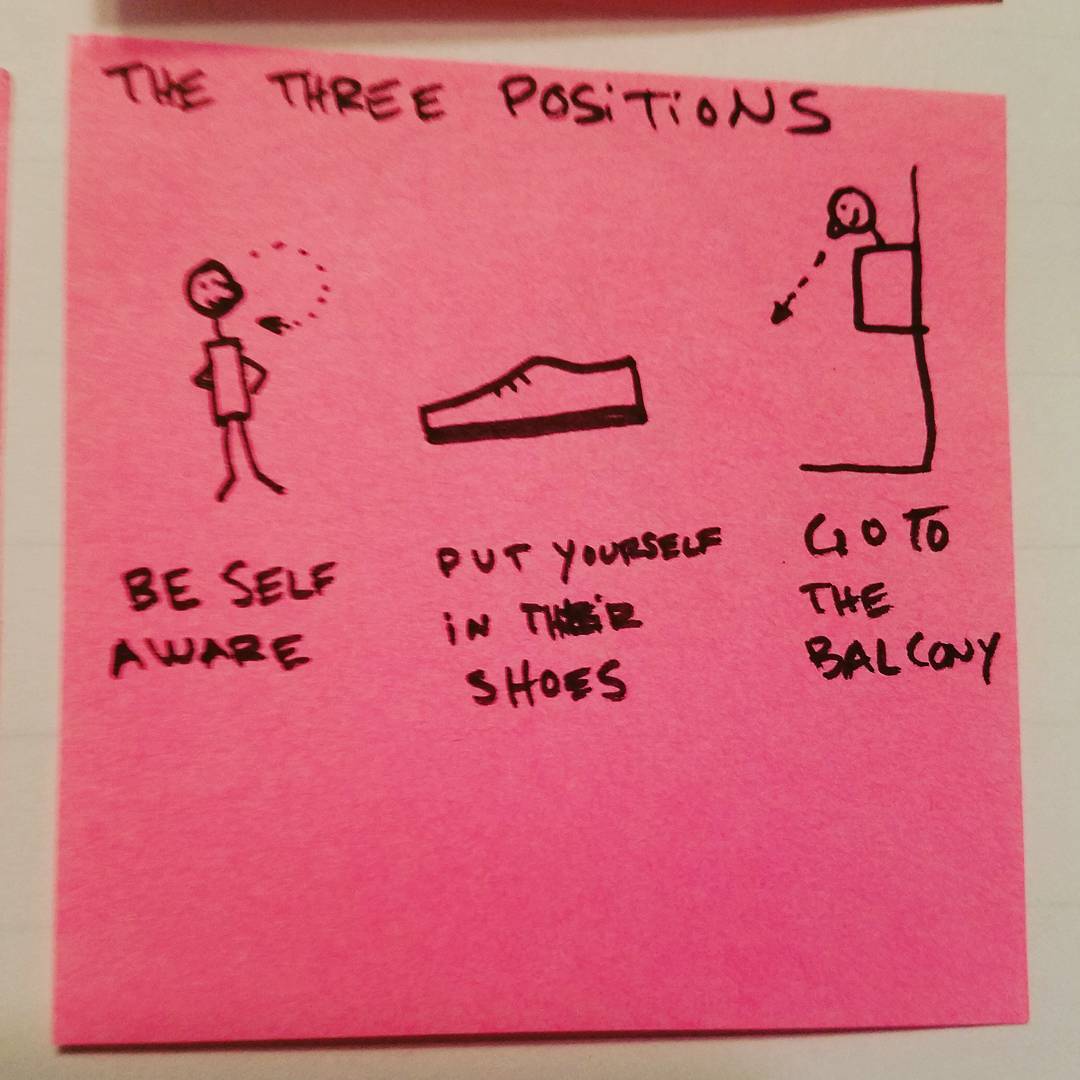

Aaron: Right, What can we change about the structure that changes the conversations. Yeah. And the nature of the relationships, right? Cause if we can change the relationships, then we've changed the entity. So how do we change the relationships between us? And that means looking at, you know, our relationships and how they touch to things like power and information flow like we just described and structure and resources and you know all the other things that we get into.

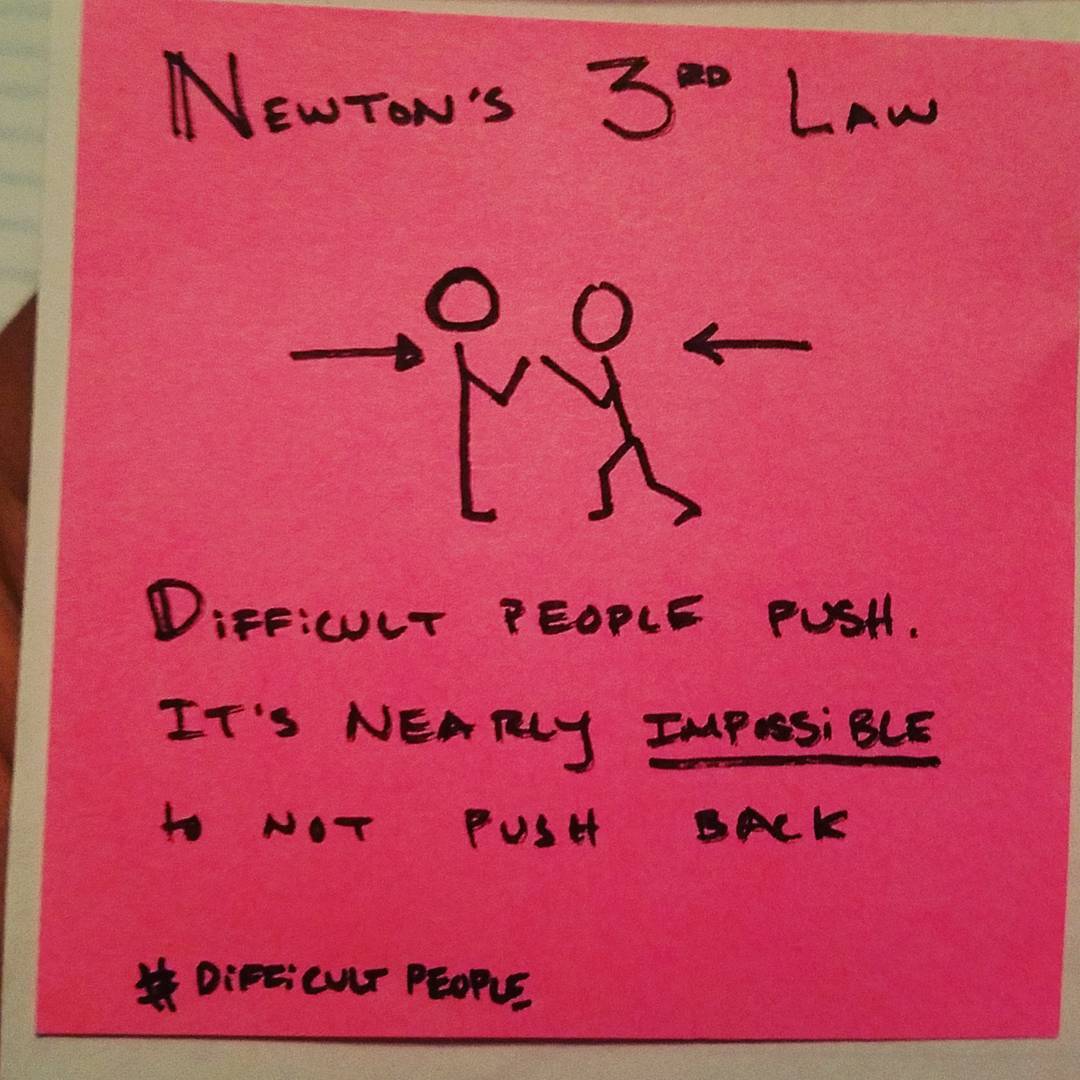

Daniel: Yeah. It's like, I mean my mind is crackling with you know, cause power. It's something I want to understand better but which parts of this is not, I'm not leading the question, where are those questions going at all, but like which parts of the conversation are hard, where does the conversation hit a snag. And I would guess that power and shifting power is one of those those things

Aaron: For sure. Yeah, I mean I think one of the things I find surprising is that the first and foremost snag is to have the conversation like that at the time and space and, and a commitment to say, hey, let's stop working.

Aaron: Let's stop rushing. Let's stop our never ending quest for growth for one hour and talk about how the way we work is serving us or not serving us. That already is, it would be a huge step forward because we just don't have the conversation.

Daniel: Yes.

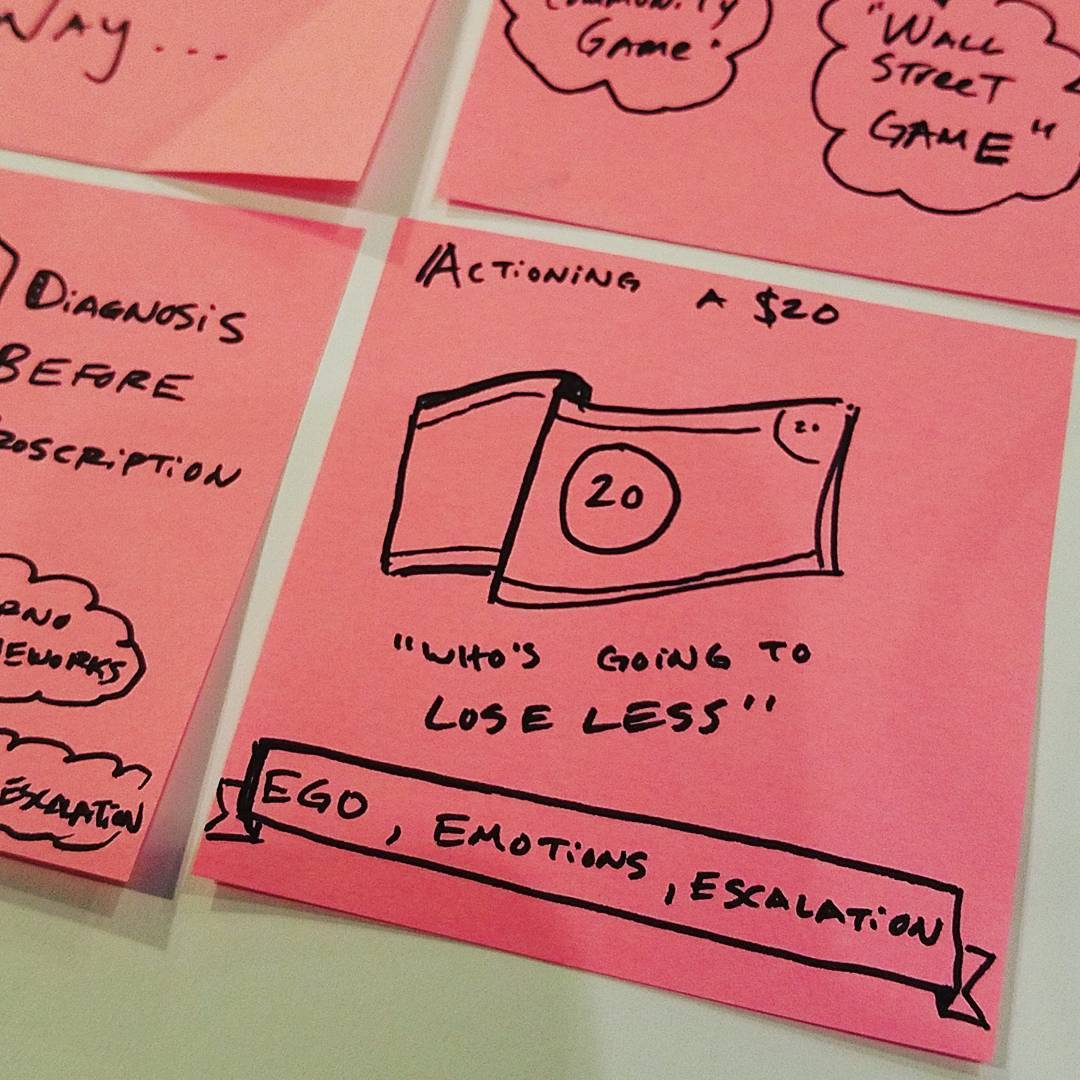

Aaron: You know, people go from meeting to meeting project or project week two week job to job until they retire or die. Yeah. And, and it's sort of like, you know, how do we actually make pause and make space and they're out the drawer a little bit so that we can think and we can observe and reflect. And so I think that's the first impediment to the conversation. And then, yeah, I think the second one is about, you know, identity and ego and power, which is, you know, if, if we're moving to a model as, as I'm sort of proposing and observing frankly in the book, it's not like I'm just making this stuff up.

Aaron: What I'm, when I'm observing in the book is organizations moving to a model that is more decentralized and requires more, um, you know, sort of more power and more ways and more transparency, um, and more participation in shaping the, you know, not just the work, but the way of working in the organization than a lot of people start to ask questions like, well, who am I then if I was the Checker, if I was the reviewer, if I was the yes, no person, then what does that mean for me? So I think there's, there's a lot of that kind of stuff going on and also just, um, the conversation of being uncertain and uncomfortable. Right? So what might happen if we, you know, what if got rid of a rule that's driving everyone crazy and we didn't have a replacement, what might happen? Right? And how do I feel about that uncertainty?

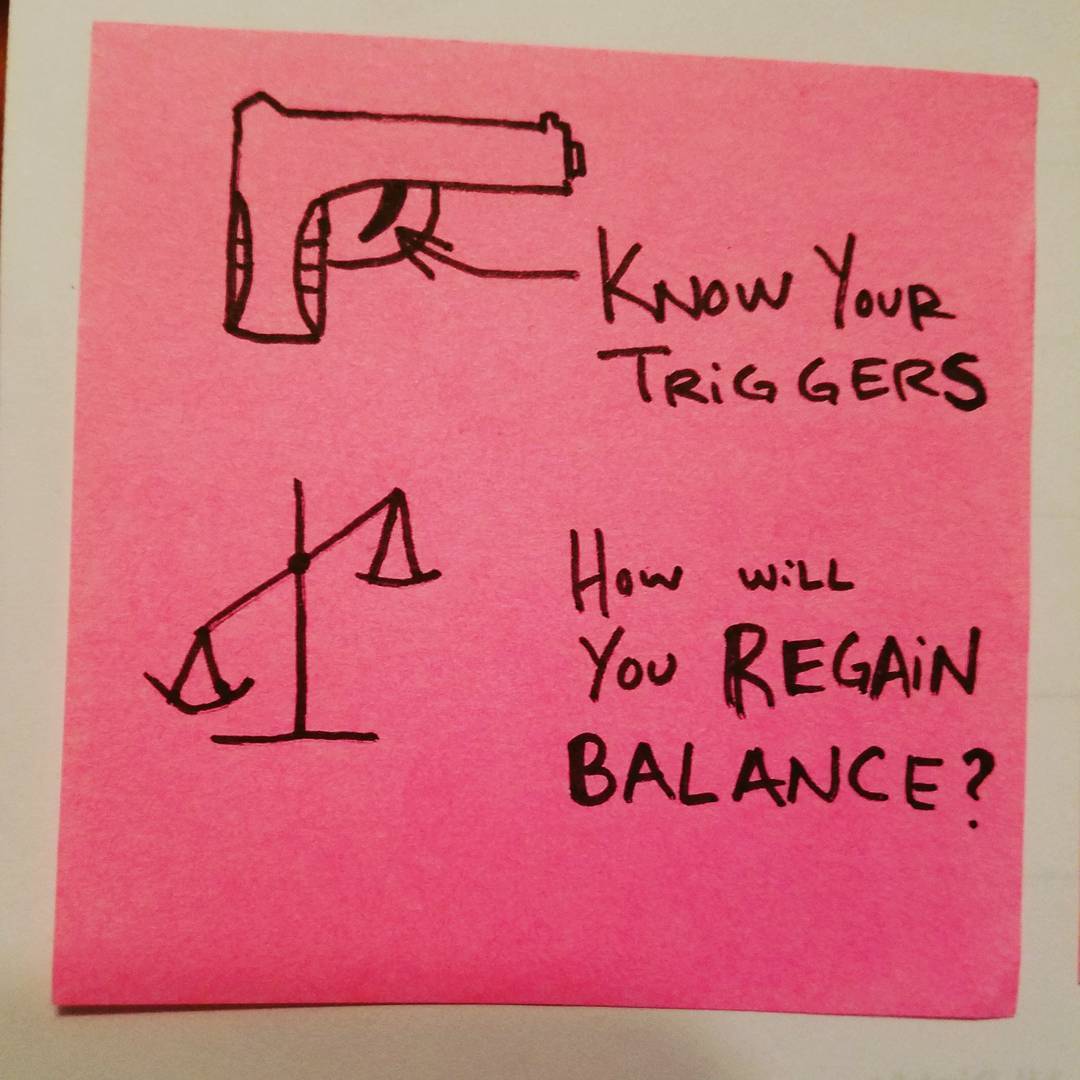

Aaron: And you know, that that control, I think sometimes even more than power is, is actually the hot button. It's the thing that we're worried about.

Daniel: Yeah. I mean, could, I mean, I don't know...is control different than power?

Aaron: Well in a way..

Daniel: Or are we, like, putting too fine a point on on that?

Aaron: Yeah. Let me see what I mean when I think the distinction is, and it may not be that you know, this is dictionary level true, but what I think the distinction is is often when I talk about power, I think about power with and over others. So how I relate to others and what I can tell people to do or not do. And you know, that kind of thing. I think about control certainly of other people, but also thinking about control of in the world, right? Can I ever really control what happens to me and to my business, my family into the market and, and this illusion of control that we're so in love with, with the plan and the, the rules and the boundaries that say like, Oh, I'm safer now because everything's in place, right?

Aaron: That when I talk about control, I sort of mean controlling the universe. Right? And not just other people

Daniel: You know, it's a friend of mine who's a senior Ux leader, he is being pushed by his organization to like make a five year plan. And he's like, no I won't. And they're like "no you have to!",

Aaron: He knows how crazy that is.

Daniel: Like I can't give you a three or five year roadmap. Like I don't know if people are going to be using apps like I don't know if people are going to be people anymore like

Aaron: right!

Daniel: But that's really scary. But we'll, so I mean cause I mean we're talking about some really fundamental things to like, pardon the French but fuck with, because this fucks with people, I mean just in my own experience

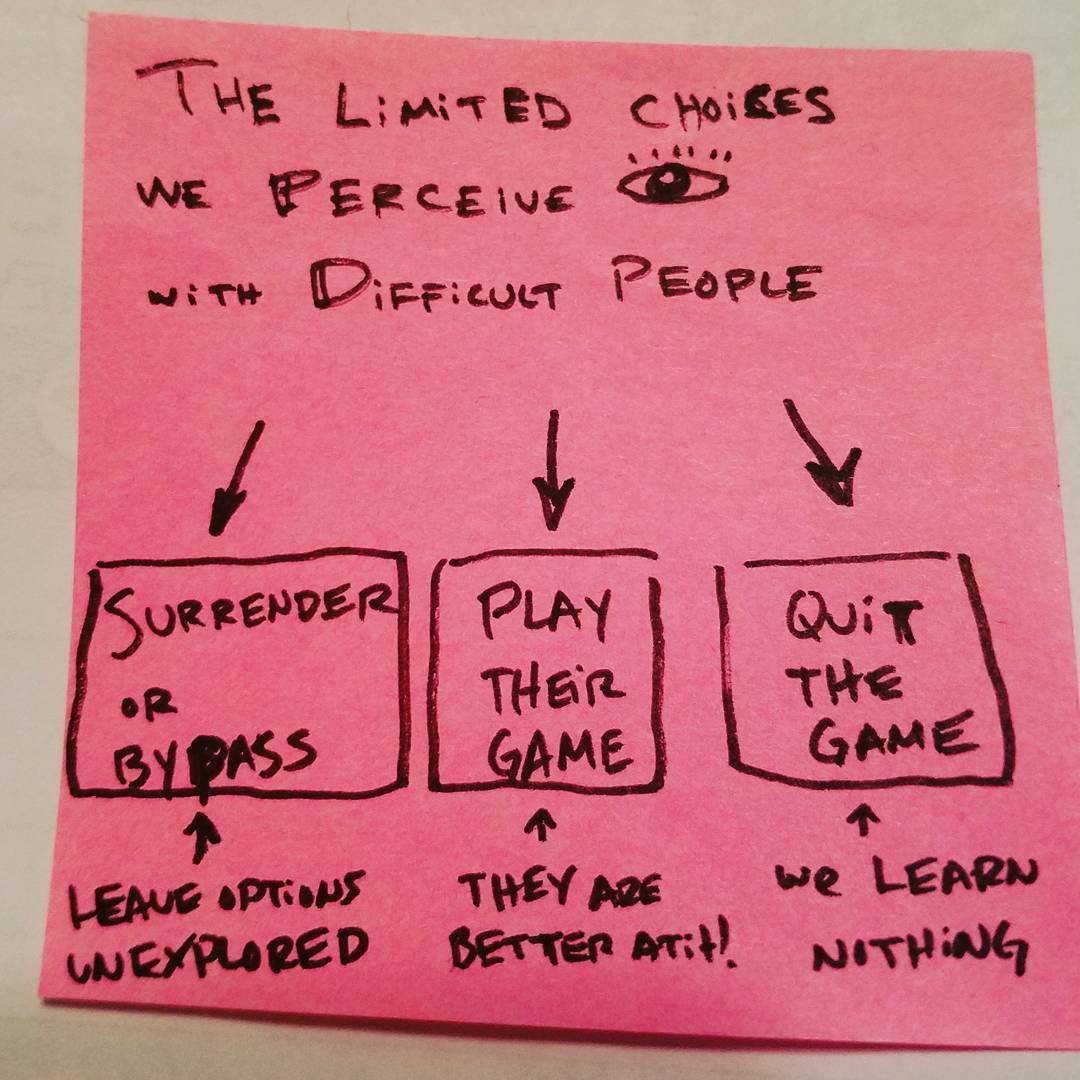

Aaron: And it's really just a trade, right? I mean I think the, when you first started talking about new ways of working and and self management and self organization and things like that, people's, I think many people's heads go to the idea of like, oh well the options then control, no control, chaos or bureaucracy.

Daniel: Like everything is false dichotomy there. Those are false dichotomies.

Aaron: And the reality is like, no, I just want you to trade one kind of control for another. So I always make the analogy, if you were, you know, sailing a boat across the Atlantic and you could steer once or every minute, which would you choose? Everyone's like, obviously I would choose every minute. Why? Because it gives you greater control. And then I'm like, cool, tell me about your annual plan. And it's like, you know, we're just doing the exact opposite in a different context because somehow it feels more like control.

Daniel: That's sneaky! That's not fair. You know the answer to that question, just setting people up to fail with that thought experiment!

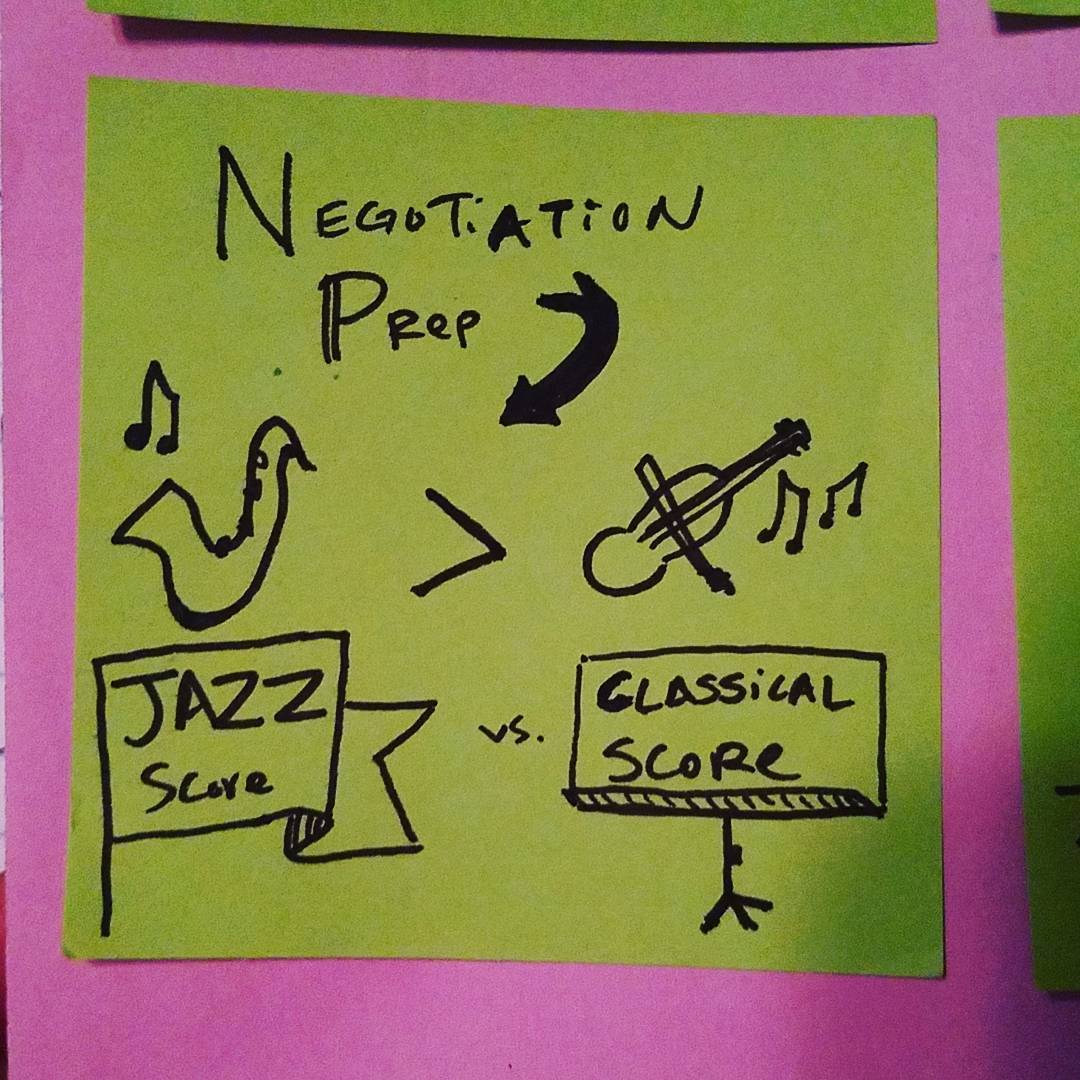

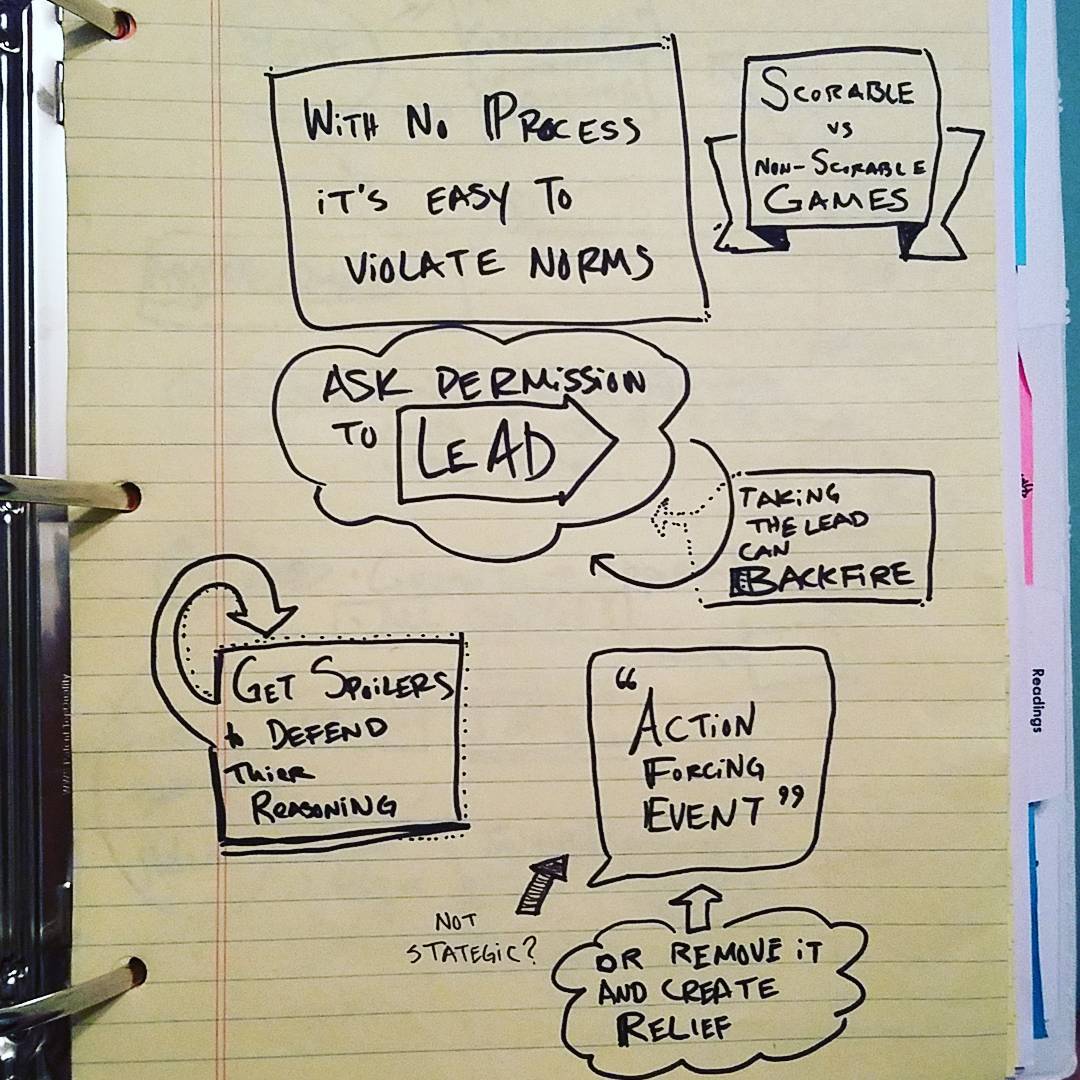

Aaron: I do a lot of that, Actually I do a lot of that in my speeches, in my workshops. So I sort of, I ask, you know, questions that, that the commonsensical answer is yes.

Aaron: The point though is, is that yes, common sense is actually pretty good when it comes to org design. Like, if you actually just listened to your comments and sentence and then translate it. It's that we have all these other ideas that we've absorbed and metastasized that, that make the way we work. So, you know, weird and Byzantine and inhuman. Yes. Um, so like we're actually a six year old is capable of designing a good organization. You just have to like ask the Socratic questions.

Daniel: Do you think this is a very potentially controversial question? Like is all of this stuff that we're trying to do create more human companies being more um, uh, distributed? Is it, uh, in opposition to capitalism? Like are...

Aaron: no, no, I don't think it is actually. I think, um,

Daniel: because it seems like capitalism like, concentrates power necessarily and, uh, it's about ownership of the system versus authorship and...

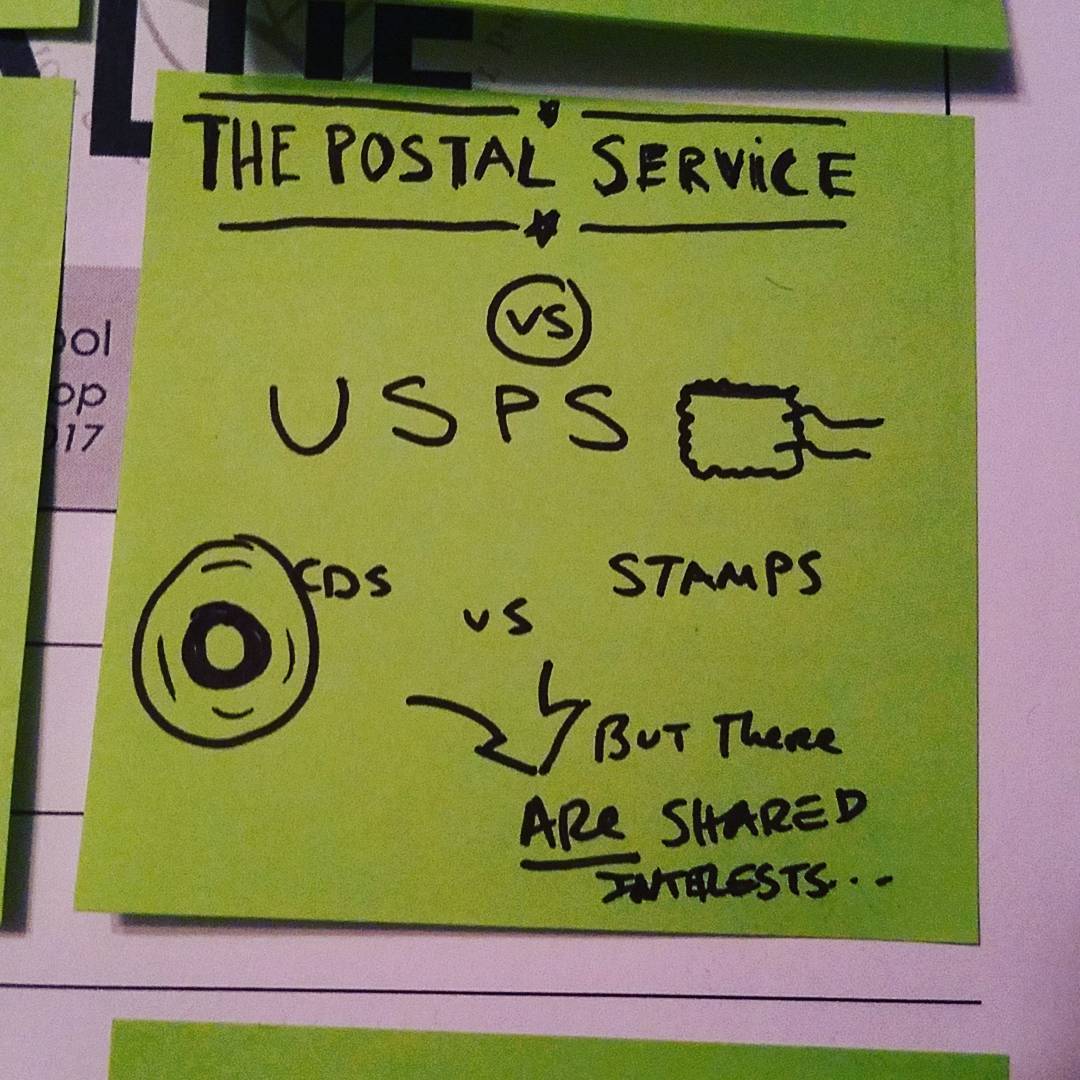

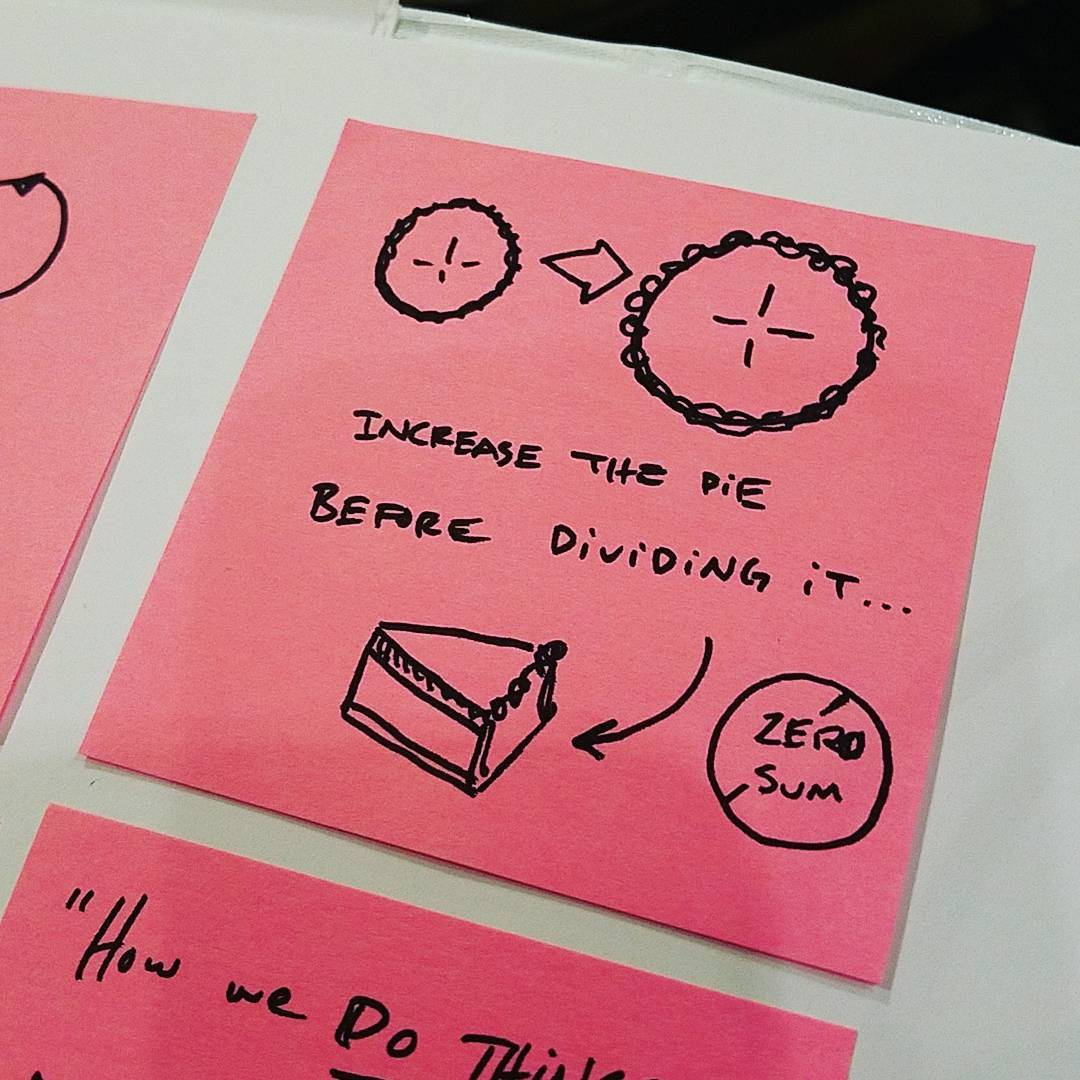

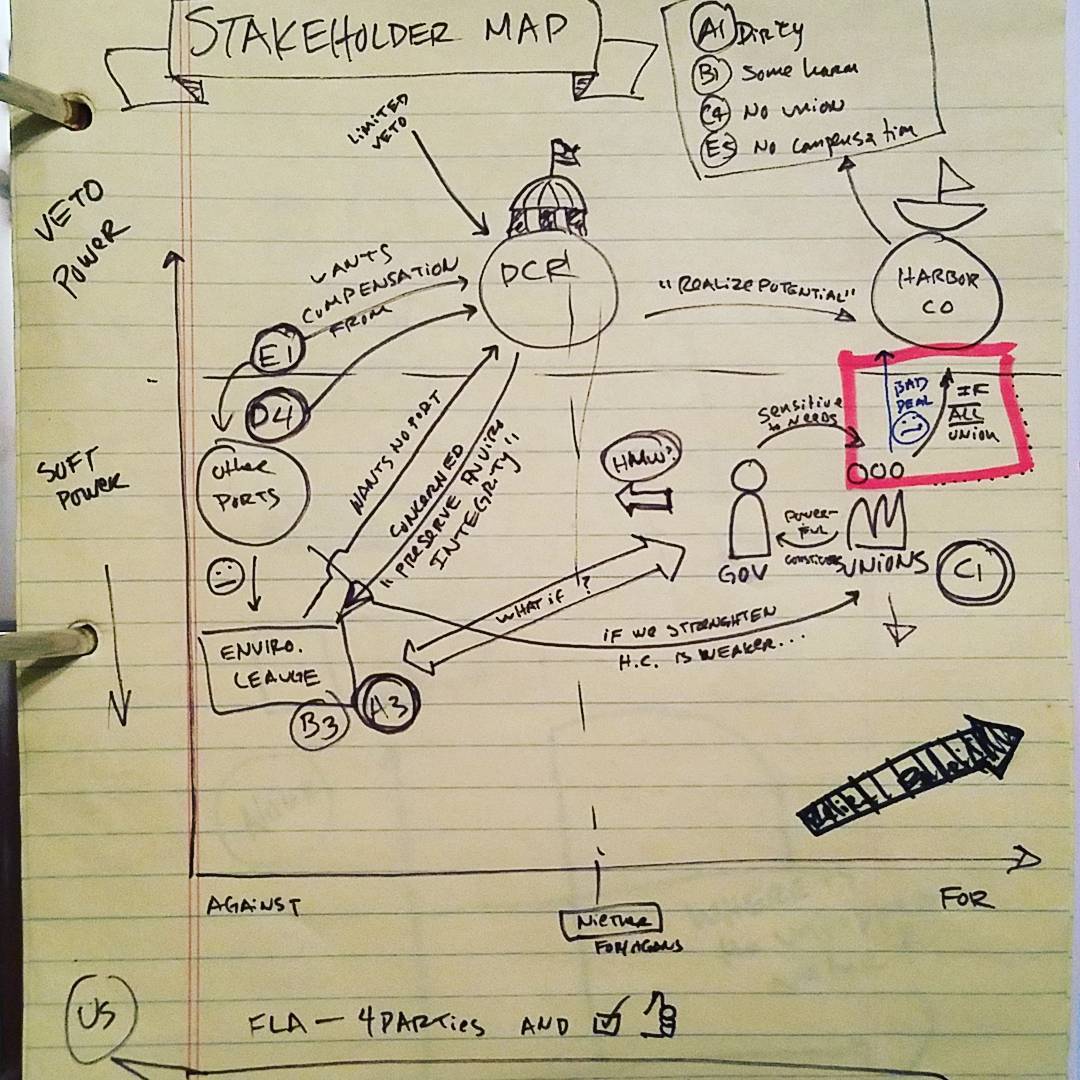

Aaron: it is in opposition to advanced capitalism and crony capitalism. Yes. Um, but I think, you know, there's a big difference between the capitalism that we live in right now and capitalism, the idea ...of you say like, do we need competition and free markets? I would say, hell yes. And in fact, most of the companies we study in the book have extremely marketplace oriented systems, right? They have people serving people in relationships and agreements that you know where the things that work continue in the things that don't work, die. So that's very capitalist. The question though is in service of what, and so if you know, if you're capitalism os basically says that this is in service of never ending growth and ultimate winners who control monopolistic enterprises, that will lead you to a very particular definition. But if the, if the free market and the competition is about who can do you know, what's best for the community, then we're still competing.

Aaron: We're just competing on different terms. And so to me like capitalism is, you know, yes, obviously there's some, some aspects to, you know, who owns labor and who owns the means of production and all that kind of stuff. And, and I think you can get into that, but it's becomes a gray area to me. Like yeah, we already live in a world with a lot of socialism and a lot of capitalism and guess what I think the future is going to contain. Bits of both. Yes. And that's all fine.

Daniel: That's not American! Aaron, first of all, I'm just telling...

Aaron: sorry!

Daniel: ...but did you ever get pushback from leaders on this of like, well if I, if I let go of this control, it's, you know, they own the company, right?

Aaron: No, actually what's funny is with people who literally own their company, they don't have a problem because they're probably quite wealthy already and they're much more interested in the meaning and impact and nature of the work they do and being less stressed out by having to try to run everything.

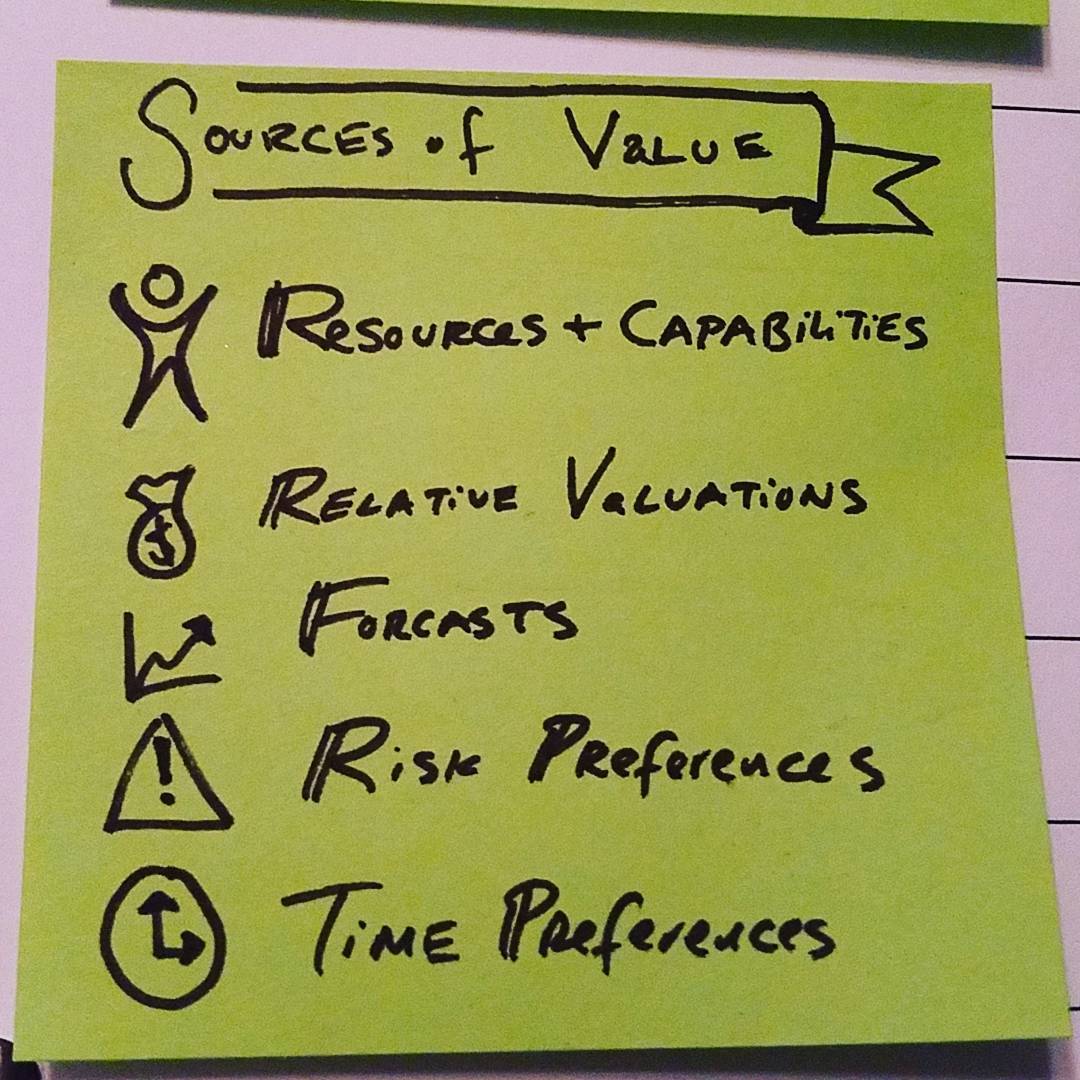

Aaron: The problem is people who run companies but don't own them, who are subject to the demands of a faceless investor class that that effectively, that's where the real issue lies, right? That you know, your, your 401k holds shares in a thing alongside a big, you know, police pension fund that are demanding a certain rate of return actually, you know, nobody's really accountable for, and then it's put on the, on the, you know, sort of before the feet of the CEO. So, but what's weird is like in the book I talk about these two, mindsets, people positive and complexity conscious and the people positive mindset was the one about how almost all the cultures and examples I looked at, take it, take it as a given that people can be trusted and should be respected and should be, you know, that they're motivated by autonomy and mastery and purpose and connectedness and all these sorts of things rather than carrots and sticks.

Aaron: And rather than saying that people are sort of inherently untrustworthy or evil or stupid or any of the other myriad things that most businesses assume in their, in their model, right?

Daniel: Yeah, yeah.

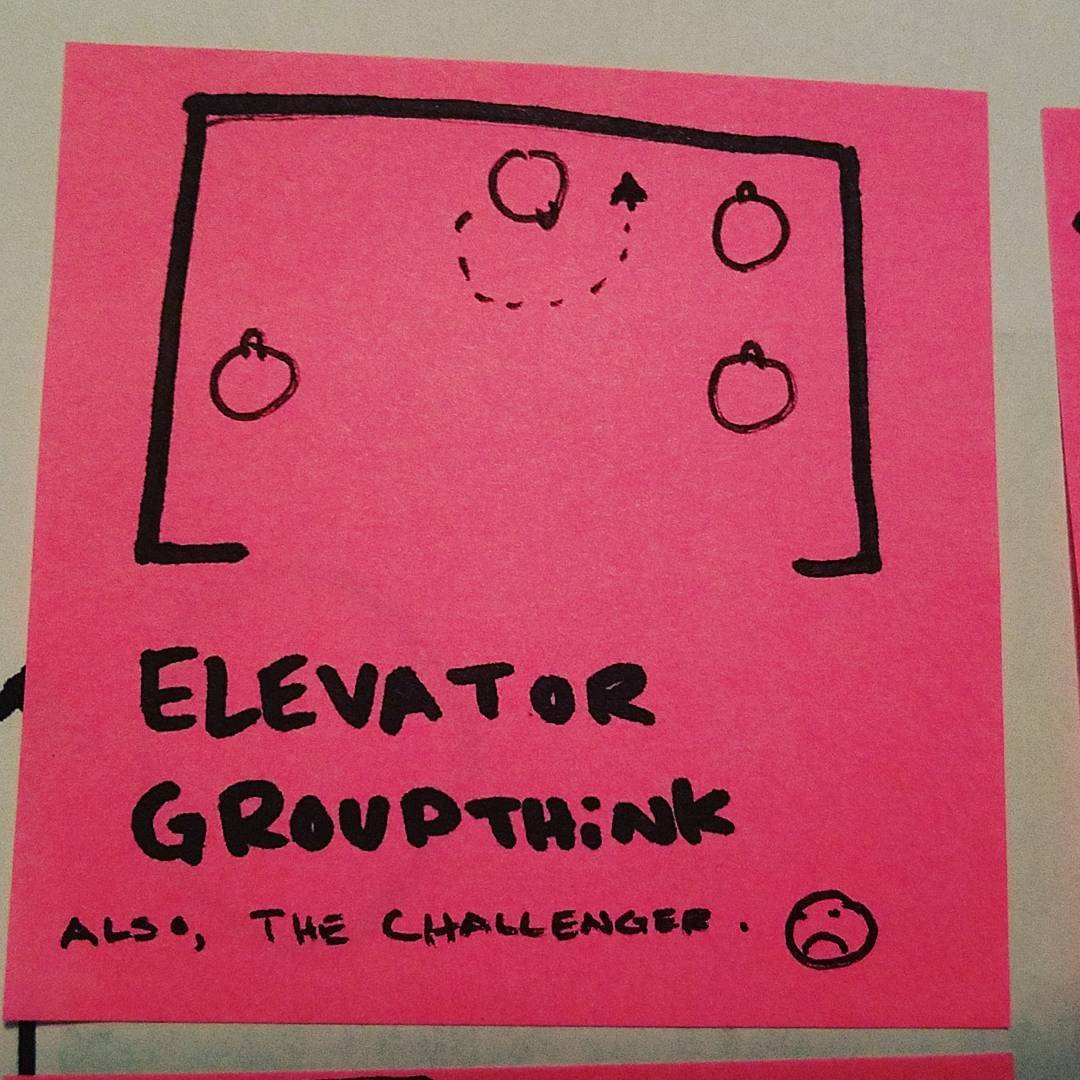

Aaron: If you, if you have a clock where people punch in and punch out, you are assuming and not people positive characteristic that people are going to take advantage. So, so that was one view. And then the other view, complexity conscious is about recognizing that the world is complex. It's dynamic, it's uncertain, it's unpredictable. And so therefore we need to, uh, solve problems and build models and build organizations to adapt to that, to be, to be able to, you know, respond and sense accordingly. And what's weird is when you put them in tension with each other, that's where things get really interesting. So it's sort of the map back to the capitalism question, you know, all way itself, the complexity conscious mindset leads to these companies that are like relentless learners at the expense of the people inside and the customers themselves.

Aaron: And you can think, you can think of who I might be referring to, right? Like you can think of companies that learn really fast, but it sounds like they're ultimately not going to be good for us. Um,

Daniel: well cause we're gonna automate everything and put people out of business, out of jobs

Aaron: but they're just gonna, they're gonna follow the data to our, to our lowest common denominator,

Daniel: out worst impulses of clicky, click, click, click.

Aaron: yeah, we end up in the Wally World. So I think that's, that's one side of it. But then the people positive side pulls in the other direction says, no, you know, what's the most humanist, most human centric, most community oriented thing we can do. And of course that left to its own devices becomes really bad because you end up making you make bad stuff. Like it's, you're not even necessarily learning, adapting, you're not, you're not competing in a market of ideas.

Aaron: And so you end up with some really lazy work and some, you know, some, not all, but some nonprofits kind of go that way where they're there. So people focused that they almost suck at what they do ultimately. Right? Yeah. They've sort of forgotten what that is when their in tension, that's when things get really interesting. And I would say the same thing for capitalism and socialism, right? Like it's when we, it's when these things tug on each other that things get interesting.

Daniel: I think it's interesting and I'm glad that, I mean like I assume you saw the, um, the Ray Dalio video where he was talking about like, capitalism needs a reboot.

Aaron: Yeah.

Daniel: And so it's great that people are questioning the rules by which we live by. I I want to talk about OSs, but I will before we go into that, like we sort of touched on this idea of theory x versus theory y and I want to make it like explicit because I think in the book you made a really interesting point that, uh, for ourselves we're like, oh yeah, I'm conscientious, I'm, you know, thoughtful. But those people like...

Aaron: those other people...

Daniel: Yeah. So like that's a really, that was kind of an interesting, I'd never really heard x and y sort of put in that sort of like us versus them way of like, well, I'm responsible

Aaron: I think it's the lake Wobegon effect like gone awry, which is that, you know, we always think of ourselves in a better light. And then when we look at others, particularly distant others, we that are very, very unlike us. We just, we attribute all these things to them that are probably not the case. And so I just noticed that, um, you know, yeah. When you think about like am I creative, am I self directed? Do I seek responsibility and greatness? Yeah, of course. Yeah. What about the people at the grocery store and it's like, oh well the people at the grocery store obviously lazy and don't give a fuck.

Daniel: Okay, so here's our opening to talk about Game Frame! You gave it right to me! I was reading game frame, your first book that you're trying to bury with this second book, there's like the woman's not the, it's like she's there on job. And on her first day she was like, okay, there's lots of stuff to do. I'm learning things. And then everything flattens out and then, "I'm bored. I'm disengaged". She doesn't, you know, she's just clocking in and clocking out. And so the thing is like, it's not her fault, it's the way the thing is designed. And that...

Aaron: That's my general thesis about all of it is that um, people are people and people are chameleons and people are highly sensitive to the culture and environment they're in. And the system, the aquarium, the container tells us a lot about how we're supposed to show up. And over time it can even beat us into submission. And so we have to change the, we have to change the system and that's hard to do when we're reinforcing things that we ourselves didn't even create, you know, um, Seth Godin had on his podcasts recently, this story of this psychological or I guess a biological experiment where they have all these monkeys, they're reaching for a banana up on a tower and they spray them with a hose. And so the monkeys obviously don't like that. So they come down and then they bring new monkeys in and the new monkees see the banana and they're like, I'm going to run up the tower and get it.

Aaron: And the older monkeys had been sprayed, stopped them and they're like, don't, don't climb young blood. And then, and then they take out over time, all the monkeys who have ever been sprayed. And when a new monkey comes in, the monkeys who have never been sprayed still stop the, the new entrant from reaching for the banana because that's just what we do here now. So it's like when I ask questions of teams, like why do you have meetings this way? Or why do you budget this way or why you need a boss that looks like that or acts like that. It's just like, I dunno, that's what these monkeys do.

Daniel: Yeah, yeah. Well, I mean, so this gets to the point of like, why is it designed the way it's designed? Was it even designed?

Aaron: Why indeed!

Daniel: and this also goes back to the question of in this happens in my work where people are already operating at 100% and when you give them new tools, you know, I go in and I teach them new facilitation methodologies or design thinking or whatever. And they're like, yeah. So it was really hard to get those two days to even think about this stuff. You know, there's no time to think about how to use these tools in our work. And so it's just like, where's the space to like

Aaron: yeah, it just bounces off.

Daniel: yeah, it just bounces off...Cause they were like, well we're already at 100% like we don't, we can't think about designing our systems because we're using our systems all the time. So there's no time to design the system or to redesign the system.

Aaron: That's right. Yeah. If I find the same thing. And in many ways I think like the, the simplest version of explaining what myself and other people at the ready actually do is we're just good at asking slash helping people make that space. Like it's, you know, at the end of the day, a lot of the value is just in having a partner who's like, Hey, on Friday we're going to not do that. Like we're going to change our rhythm, we're going to make space and we're going to kind of hold ourselves accountable to that. And, and if you're not ready to do that, obviously it's not going to happen. But if you are ready to do it, I think having, having someone around who's encouraging it and coaching to that is almost more valuable than the ideas. And the, you know, new fangled way ways and not like all that's great, but you can find all that if you stop anyway and just pay attention.

Daniel: So like if, I mean the kind of clients that you and I work for are ones that are asking the question. Um, this is like, this is, oh, it's Passover coming up. This is perfect. Um, this won't release during Passover, but, you know, do you know, do you know about the, the, the, the, the question, the four questions. In other words, there's a story of the three sons, um, and, and uh, one of the sons, I'm going to get this wrong in the middle of like a horrible Jew, but the, the idea is like, one of the sons says like, okay, well what's going on? Like why is tonight different than all other nights? And you're like, okay, well here's why. Like, where's his, why we'd Matzah this is why you tell them the story of Passover. And then, um, the other son's like, well, why do you do all these things?

Daniel: And so he's separated himself from the question. And then the, the response is to say like, well, this is what God did for me when he brought me out of Egypt and this is what you speak to your own experience. And then there's another son that where they're just like, they don't even know how to ask a question. And, and for that you sort of like take time and you really stretch it out and you break it down piece by piece for them. And I imagine that there's like the spectrum of people who read this book, some of them are like, this is already a priority for us and we have budget for it. And that's why we're going to make time and space for it by paying consultants to do it. And there's others who are like, not even asking this question and some who's gonna read this book and they're stuck in the middle of this fershlugenah organization (that just working my Yiddish in there and get it in). And they're like, where does somebody start when the, when the company does not have the extra resources, right. Mental, emotional, physical to be having this dialog.

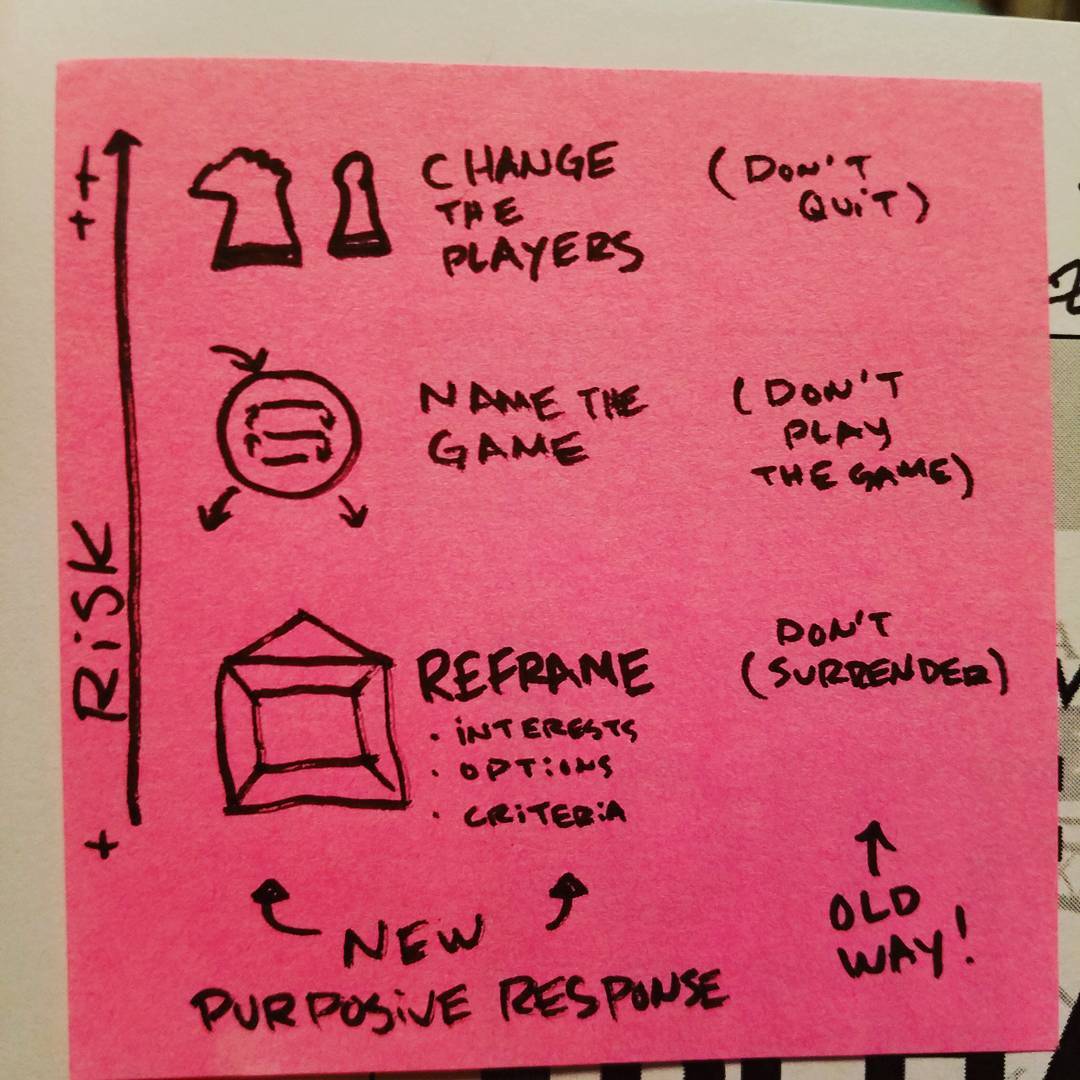

Aaron: Yeah. And I think, I mean, if somebody reads this work and it speaks to them, then I think that's one thing and it doesn't speak to them and who cares? Um, but if it does speak to them. Then they kind of have two choices. And I've seen people go both routes. One is that it feels like the organizational debt is just too high to pay off and by that I mean, so many policies and practices and norms are out of whack. That and the level of openness is so low. Um, then the easiest thing might be to just not work there. Um, and if that's a privilege that you have, then it's a privilege you can enjoy. Yeah. Not everybody has that privilege, but I think if you can choose where you work, then choose better.

Aaron: Um, so I think that's, that's one piece. But the second piece is if you, if you choose to stay or are you have to stay, then you can start where you are. And that means, you know, do I lead a team? Do I have, do I lead a project? Do I have an open ear of someone who does? Um, so that we can start by asking the question, you know, what's stopping us from doing the best work of our lives in this domain, in this space, in this sphere? And then start, um, start iterating, start playing with, with, with how we show up. So I think sometimes we get overwhelmed by the scale and the magnitude and all the other people we have to convince and it becomes this big thing. But reality is like, at least 50% of the stuff is driving us crazy is right here.

Aaron: You know, is right...And they can't see me. I'm waving at my face.

Daniel: Aaron's actually the problem, everybody. that was a metaphorical...

Aaron: So it's in the way for everyone. Like it's, it's going on with us. How we, uh, how we meet, how we share information, how we plan our work flow, how we do what we do. And then, and then certainly the people we're closest with, our teams are our colleagues. The people that trust us. Like there's, there's a lot going on just in those small pockets that frankly, you know, if you move on some of the stuff and you move it in the right direction, everybody else notices and they notice the, the energy and the engagement and the commitment and the service level that your group or team is providing. Um, and they start to be curious themselves.

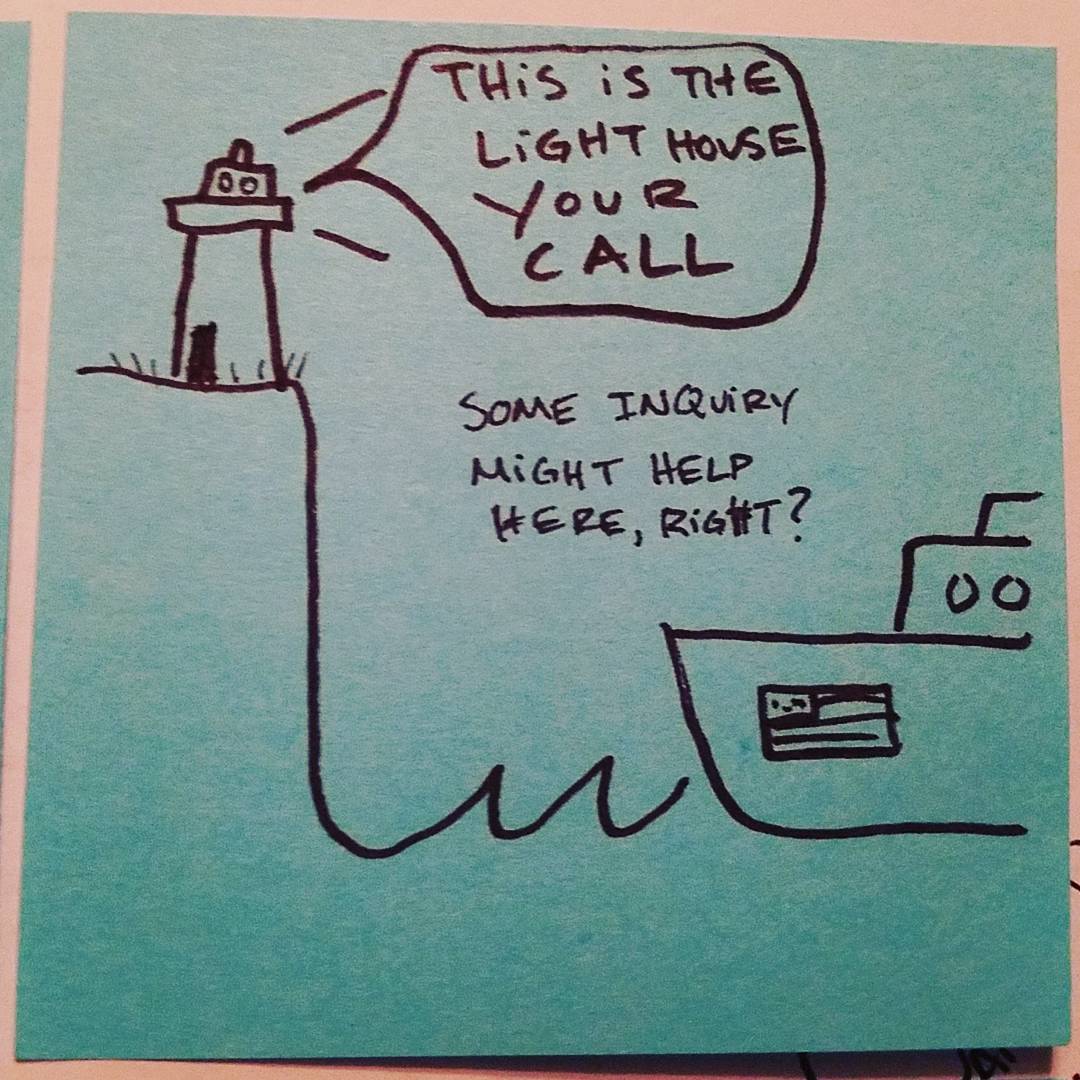

Aaron: So I think the best way to create curiosity sometimes is to, is to just start acting where you can. Yeah. And then the other thing is, you know, being brave enough and it's why it's called brave new work, you know, being brave enough to ask these questions in larger forums like to ask, because one of the things I find is people are like, oh, I want to change this, this and this, and I go to my leader and maybe they won't like it or they won't agree or they won't hear me or I already have and they don't give a shit or whatever. And I'm like, don't ask, don't do that. Go to them and ask, what do they think is holding back the team from doing the best work of its life? And then they'll say, oh, well, you know, I, this is like everybody has an answer to that question. Everybody's got a thing that's on their mind that's, that's holding the organization back. Nobody's ever like, oh, it's perfect. Just keep doing what you're doing. So though when they say, then let's start there, let's start with what's true for them. And that's a way to invite and open possibilities up. So I think a good way to...

Daniel: I'm a big fan of that word invitation. Uh, you know, in my own model of conversations, you can either just initiate them or you can invite them. And what's interesting about the canvas is this idea, this is, I think this is a direct quote. The canvas can provoke the conversation. I also feel like it contains the conversation and in and in both good ways.

Aaron: It focuses it

Daniel: Yes, it focuses it and provides, like in my language, every conversation has an interface, something that mediates it. Like, like the luminiferous ether of, of space and time. But it's like, it's like it's an interface for the, for the dialogue. It's a place where it can happen.

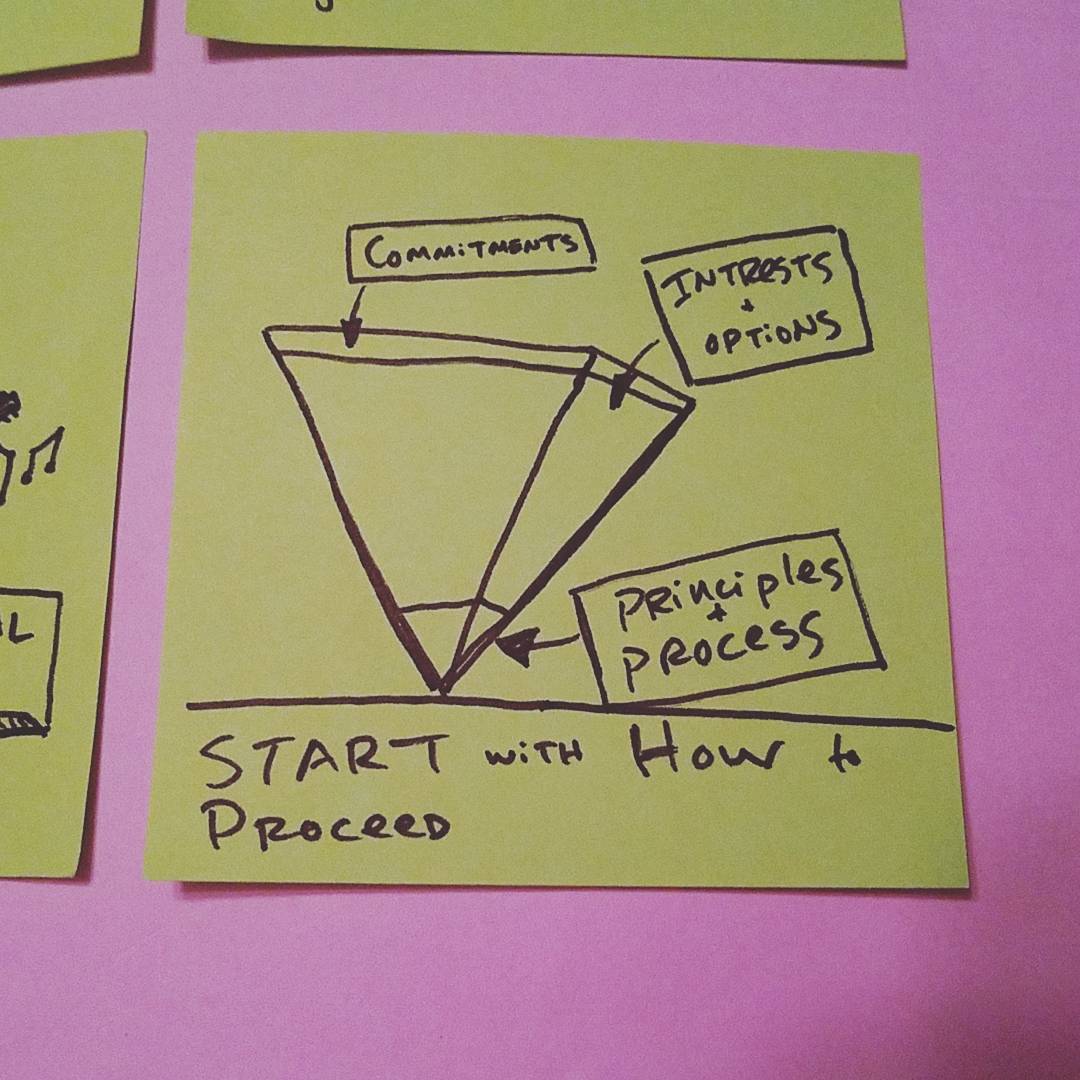

Aaron: Yeah. And I, I did not want to create it as a, as sort of a frame or a tool to limit, but I did want to create it to focus because if you've done this work for awhile and you've had these conversations and you're, and you're digging deep, you're going to find all these nuances and interconnections and other things you want to talk. And that's all great because now you're doing it like it's going to the gym, your 500th time versus your first time, right? Like 500 time at the gym, you can make up your own circuit, you know what I mean? But, but for the people that I was encountering that were sort of coming to this fresh are coming to this for the first time or in a long time, they were kind of like, there's so much in our way of working. Like where should I begin? Where should I look?

Aaron: Where should I, where should I start to ask questions? And so the thought was these 12 spaces are the spaces where the organizations that seem to be working most differently that have ditched bureaucracy and found more human, more adaptive ways to work. These are the spaces where they're doing things most differently and where they're most aggressively flipping the table over. And so it's a good bet that if you dig in these holes, you're going to find little opportunities and treasures and, and things to, to act on. And then, yeah, if you want to go beyond that, are you, are you figure something else out? That's great that I'm not trying to restrict that, but I am trying to say, boy, if you haven't asked yourself the tough questions about these 12 spaces, we haven't even done the work of 21st century org design. Like you're not even there.

Daniel: Yeah, yeah. You know, it's, it's amazing. And I, and I wanna I want to honor your work because like I read the medium article that you wrote almost like 2015. Now it's long time ago when it was just nine elements and uh, um, I think the idea of a, an operating system was interesting and inspirational for me and in my own work, you know, so the book that I'm working on, I think I sort of tried to ask myself like, what is the smallest number of elements that one can think about to make a canvas for what, what is controllable and what is alterable about a conversation? And it kind of blew my mind in the book that you, that you expanded it from, from nine to 12. Um, changing the symmetry significantly and, but also maybe being, is it, is it, is it MECE now is, is that even, does that matter?

Aaron: No, but it is, but it is more MECE now. So it's not,

Daniel: Oh, and can we define MECE for those people who are not as geekalicious as you and I are...

Aaron: mutually exclusive and comprehensively exhaustive. It's actually an old consulting term. Yeah. So, no, it's not, it's never, it was ever intended to be. But what I found is that the first version, while it had nine boxes, really each box had many words in it. It was like a run on sentence in each one. So it wasn't really fairly nine things. It was, it was these sort of groupings of things

Daniel: you've chunked.

Aaron: Yeah, they were chunked. And so it was arbitrary in a way. And what I wanted to do is actually simplify it and say, all right, one big idea, one focal point in each space. And, and so in a way the 12 is actually a reduction.

Aaron: It's actually a simplification of what was there before. It just feels like more of a pain in the ass. I mean 12 not that many things. Um, right on top of things of things that you could, you could count. There's lots more numbers. There's 12 months. We can name them all. We're fine. Totally.

Daniel: So I think the thing that's really amazing is that in the opening of the book, I think you, you explained this idea of an operating system very well using the intersection analogy. Like, I don't know, where did, did the operating system concept come in from the game frame book, like your interest in games on, like how did that sort of filter into your brain and then into my brain?

Aaron: No, I mean I think it was, this is a, a way of using that phrase or that, that term that was bubbling up in culture in lots of different pockets I think over the last decade. In some ways it's a bastardization of the term, right? Because if you should go real technologists, like an operating system is a very specific thing and it's not this thing. And I was like, and then I, and then I talked to people on the, on the very like sort of teal, you know, um, new work side of the spectrum and they're like, an operating system is way too mechanistic a metaphor. It's a terrible metaphor for that reason. So, so I'm like, I don't, I don't appeal to either. I'm not trying to appeal to either of those things that I'm trying to say is there is a a system of operating, a way of operating, a way of being in the world and it's made up of assumptions and principles and practices and norms and patterns of behavior and it's coded into the system. It's sort of, it's the foundation upon which other things happen.

Aaron: And so what I mean by that is like, you know, we walk into a conference room and there's a table and chairs in there, table and chairs, our assumptions are baked in from the get go and no one who works in the company gets to change that. That's just the way things are. And so if you want to do something in a meeting where you want to move people around, tough luck. If you want to have another whiteboard in that space, there isn't one. Like it's just the choice has been made for you. And I think when I was, when I was originally scratching at was this idea that there seemed like there all these things in culture and the culture of business, particularly Western business that were like, the decision has been made for us, we're going to have an annual budget.

Aaron: That's how it is. Nobody even thinks to say, wait a second. Does that make any sense anymore? Did it ever make sense? Yeah.

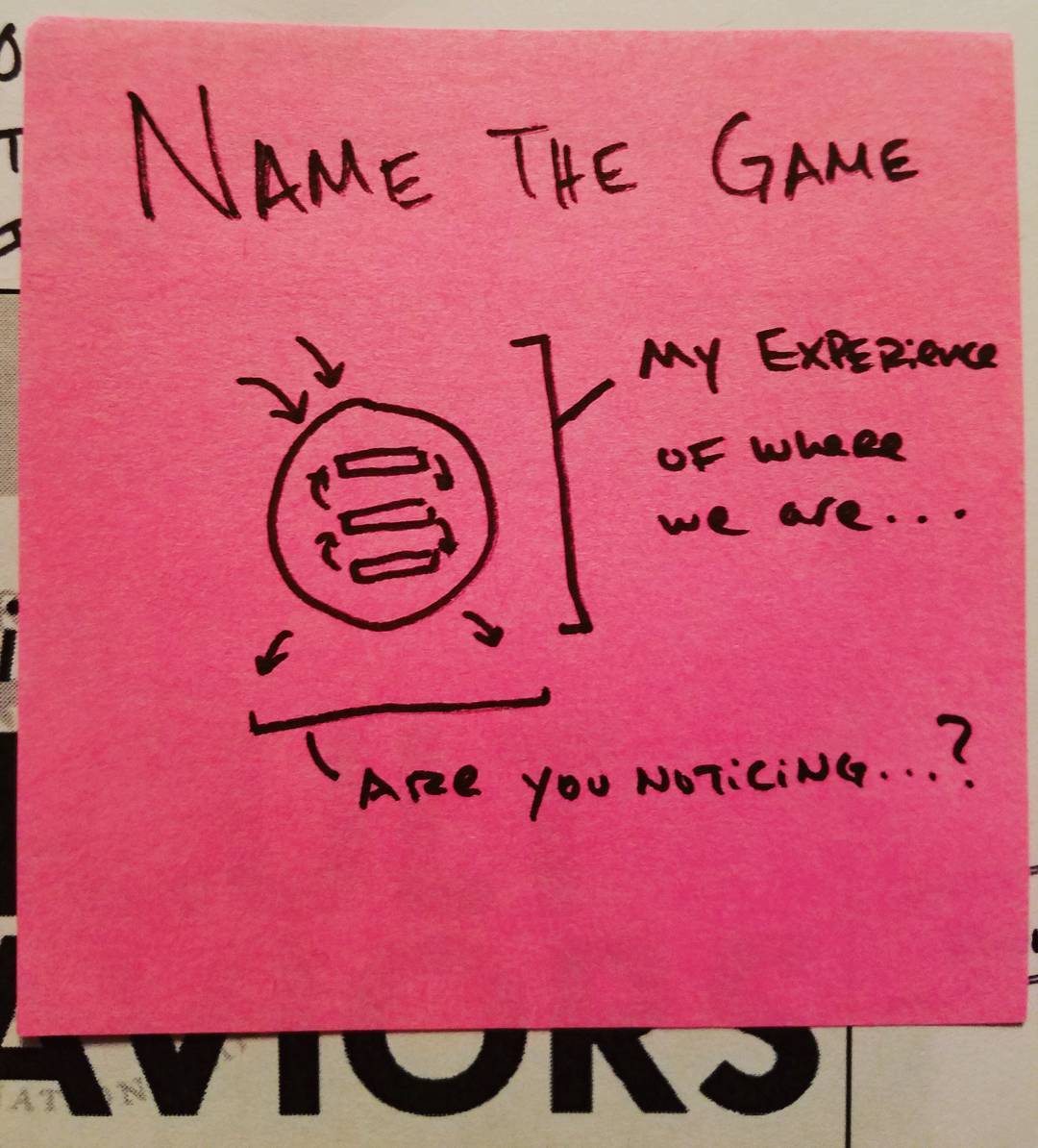

Daniel: And this is the water the fish are not noticing

Aaron: exactly. Yeah, this is water. Yeah. So, so I think, um, that was the thought. So I don't mean it literally, uh, I, I just mean, you know, I know as a way of working a, a set of assumptions and, and so, uh, that metaphor, good or bad has really helped people that I work with connect the dots and be like, Oh yeah, I get it. Like there is an underlying set of stuff that we're living and breathing in and that might need to change. And so what does that look like?

Daniel: Yeah. But I, going back to that mechanistic thing, it's, it's um, I mean we're definitely, it's, it's, it's, it's interesting that we're using a technological metaphor instead of like a truly mechanical metaphor. We're using a metaphor of our age that people understand this idea of like an operating system and applications you can install on it.

Aaron: Yeah. But one, by the way, that's one way to go with it. I take umbrage at that as well because I'm like, look, DNA is an operating system. Physics is an operating system. Like don't tell me that they're not.

Daniel: They are, well, I mean, as a person with a physics degree, I would say I have a hard time with physics as an operating system versus like, the geometry of of space and time.

Aaron: But that's what I mean, the, the underlying first principle rules of physics or an OS layer on this universe and like do stuff that they don't allow.

Daniel: Sure. I mean with the presumption that there's, and, well this is an amazing rabbit hole, but there are other universes within our multi-verse where gravity is stronger. Right? But there's still gravity.

Aaron: And there are other companies for whom their OS is different.

Daniel: Yeah, totally. Well, so here's the thing. You cannot, uh, cut and paste somebody else's operating system, right? Like, which is, which seems frustrating, I would guess to some people where they're like, can we just do 20% free time and be, you know, as profitable as...

Aaron: Yeah, and we'd be Google

Daniel: Right...and be Google …can we do, because the cookies are not Google. I mean the cookies in San Francisco, Google, San Francisco office are delicious, but that's not what makes Google, Google. That's an outgrowth. You're looking at the wrong thing.

Aaron: Right. And also, I just think again, it mistakes the Organization for the complicated system. Like a watch and not a complex system like a garden. Yes. You know, you can't, you can't rubber stamp. So yes, if you, if you like my watch, you can buy all the same parts and build your watch. It'll be exactly the same. It'll work just the same. Yes. But if you like my garden, what are you going to do? Yeah. Talk. The only choice you have is to nurture and grow and look and try to compare and see what works and what serves because your sunlight is going to be a little different and your seeds are going to be a little different and your soil's going to be a little different. You can't rubber stamp my garden.

Daniel: Yeah. Micro climate. It's a thing. Um, so like the thing that's, um, it's, it's on my, my sketch notes near this, this idea of uh, the, the moon and the finger pointing at the moon. And this is like, um, I grew up reading zen, zen flesh and bones and I was sort of like pleasantly surprised to see that story, that analogy in your book. And maybe can you talk a little bit about that idea because it seems relevant to this context of the goal versus the path.

Aaron: Right. One of, one of the, um, results of having a culture of work that really came out of a factory model and that came out of a very mechanistic, complicated oriented model is that we, we want things to be the one best way and the answer and the method and the checklist and all that sort of thing we hunt for that were actually trained to look for that in business school. You know, the whole idea of the MBA business case, it's sort of like look for the lesson and apply the lesson liberally everywhere else you go. And so that we look for that stuff. And as a result, a lot of the emerging trends in ways of working like agile or lean or open or you know, you name it, um, are become kind of get turned into something else other than what they are.

Aaron: So instead of looking at like, what is the essence of agility, we look at capital A agile, how do I get certified as a scrum master? Right? And one of the boxes I have to check to be a, uh, you know, scrum organization and now I've done it and I've checked the box. And so I've done. And so the point of the, of the story obviously is that if you, you know, if you mistake the finger pointing at the moon for the moon, then then you sort of go down this path that is not wise, that you lack the wisdom. And in the same way, you know, when people get obsessed with the tactics and the practices and not the principles and the, and the meaning, they get lost as well. So there's so many teams I've coached who are like, Oh yeah, we, you know, we use a Kanban board already.

Aaron: We're hip to that. We got that stuff figured out. Cool. Why, why, why, what does the Kanban board, why a Kanban board, what does it do? Like what does it mean? And they're sort of like, it's the, it's a box that we chat. Like we're doing it as opposed to saying like, oh, well, you know, theory of constraints and here's how I think about flow and stock. And like, you know, all the ways in which

Daniel: Transparency!

Aaron: Yeah. Like information radiators and all this stuff that would like explain that they understand the reasoning behind the math behind that practice. And if you took it away, if you'd like, you can have a Kanban board, they'd be like, we can figure out another way to have all those things because we understand what all the things we're trying to have actually are. And so to me, the finger pointing at the moon was just a really good, you know, obviously little piece of Zen wisdom. But the idea that like, we love to look at the finger and we love to standardize and we love to sort of get preoccupied with the, with the best practice and with like, you know, the magazine article on what the cool company does.

Daniel: Yeah.

Aaron: It's much, much harder to wallow in the reality of figuring it out for yourself.

Aaron: That's true. Right. It's, it's because it's, and it's, and that's why, you know, conversations are messy and organic and fluid and, uh, there's no endpoint necessarily, right? Because right. Raymont until the company goes out of business,

Aaron: you can't, you can't borrow wisdom and you can't finish. So it means that you to decide to be a player of the game. Right. You know, you have to, the infinite game is something you have to be like, I'm going to do it.

Daniel: I'm so glad that I feel like every interview eventually has to touch on finite and infinite games. One of the books that everybody should read if they want to understand how the world is, well, how did you find the book that, that, um, which we would used to be a big secret. And now like Simon Sineck, as you know, I'm not going to get ripped off. Yeah. I mean, I'm a little offended that he's like, yeah.

Aaron: Well, I hope he does. I mean, obviously it could go either way, right? Like you could be, it could be very much a regurgitation of someone else's great work. But what I hope he does is um, mainstream at more because it, it is a secret thing. Like it is a kind of like passed from one person to the next kind of a book. Yeah. Yeah. I'm not sure that it never found its full footing. So if nothing else like, like I like seminar, the big platform can maybe help it find, find broader flooding, a best case scenario. But um, yeah I honestly don't remember how I got it. That's the whole point, right? It was like, it was sort of, it was handed to me. Um, and you know, and I think it's, it's an idea whose time has come for sure. Cause we, we've been obsessed with the finite for the last century and you know, start it's time to start thinking longer term than are the front of our own nose. Yeah. Is that, is that the sort of the fundamental yeah.

Daniel: What was the life lesson you took from that book? Like what, where, where does it, where does it live for you? I can tell you where it lives for me.

Aaron: Um, I think there's a lot of lessons to take from it. Obviously. I mean it's, it's, you know, how attic and weird and it's applications. My, my take is just that simply that, um, you know, they're like operating systems. There are different ways to approach problems and there are different ways to approach showing up in systems. And if we, you know, there are, there are games that are deemed finite and that have ends and winners and things like that. And there are games that are deemed infinite and don't have winner and continuing or more conversations, et cetera. I think what is, what is not necessarily set overtly in the book, but that I believe is that like the, that's totally arbitrary. Like we get to decide which games finite and infinite. And we, and so as a result, like when we, when we characterize it the wrong way, we've, we lose. And if we, if we characterize businesses finite, we lose. If we characterize politics is finite, we lose, if we characterize the environment as finite, we lose. So, um, so in some ways I think it's just about, uh, elevating, you know, to it, to a higher level of play. Yeah.

Daniel: Yeah, totally. Um, so we're, we're almost at the end of our time together. Like, is there anything we haven't touched on that you think it's important for us to, to dive into about,

Aaron: I mean, this has been, this has been pretty far reaching. Yeah. I haven't attended the physics operating system of the multiverse. I feel like I would be remiss to criticize the size, the scope and breadth of the conversation.

Daniel: Well, fair enough. I mean, I'm looking at my notes. I think, I mean, I guess the one question I would have is like his bravery enough.

Aaron: Hmm.

Aaron: I think it, I think, yes, I think it can be, um, you know, obviously the work that we face ahead of us to rethink our institutions. And I mean that very broadly, um, is, is huge work and it's the work of the next decade plus of it's the next generation plus that have to have to deal with that. And so I think the question is what are we willing to risk, um, and what are we willing to give up. And in many cases, you know, to let go of one vine, you have to grab the next. And you know, there's like a little bit of a, of a fear and a vulnerability and an a loss that goes along with that. So to me, I think the bravery, um, if we had a lot more of it would certainly go a long way. The bravery, you know, to be, to be vulnerable, to be bold, to take risks, to leave space to, you know, to do more with less. You know, all those things I think require us to sort of face ourselves and, and face the void. Um, so yeah, I mean, I mean Shit, you know, we could, we could use a lot of other things too, but I think if we had a lot more bravery, uh, pointed at how we work and solve problems together, um, that would, that would be quite far reaching.

Daniel: Yeah. Yeah. I think that's really powerful. And also just like the thing you said about loss, I haven't published it yet, but I did have a wonderful episode with um, with Bree Groff who obviously, you know, um, her, we talked a lot about this idea of like, change requires grieving loss and dealing with, with, with loss and letting go of the, of the old. And so I think that's like,

Aaron: Yeah, it's a rite of passage, It always is

Aaron: Yeah. So I think there's like that piece. Yeah. And we maybe don't talk enough about the sort of like, I think maybe there's a yin and Yang of, of bravery and also grieving.

Aaron: I think that's true. Yeah. I think that's very much very much the case. But of course you can't, you can't grieve what you're not ready to, to lose so that, you know, they go one there, one, two punches. I think, uh, which we could use more of all of it. Yeah. More of all of that. I say "pay attention...bring it!"

Daniel: So, I'm going to conclude our conversation. Like people can find you. Where should people go to look for the more of the things about, you know, all the, all things Dignan... Like obviously they can just Google brave new work and they'll probably find you

Aaron: They'll find stuff. Yeah. I mean bravenewwork.com is the site for the book, which is nice. And we've got information there about, uh, workshops and other things going on around it. Um, the ready.com is the site for the organization that I work with, with that sort of tries to do this work in the real world. And then I'm uncleverly Aaron Dignan on almost every social platform that I participate in.

Daniel: So it's reliable. That's, you know, there's nothing wrong with that...

Aaron: Full name, no spaces, hyphens, no underscores, just

Aaron: not love death and robots..Dot..You know, whatever?

Aaron: No, No, none of that.

Daniel: Well that's, yeah, that's pretty straightforward. Um, Mr Dignan, I really appreciate you making the time for this conversation. I'm glad we made it happen.

Aaron: Yeah, me too. Yeah. Thanks a lot. This is fun. And, uh, you know, we'll, we'll talk again when something happens or the next one happens.